Flood-ravaged Vernonia stakes its future on a new green school and the hope of what it can ignite.

Flood-ravaged Vernonia stakes its future on a new green school and the hope of what it can ignite.

By Robin Doussard

|

On June 27, the first wall was raised on Vernonia’s new K-12 school, which is sited on 32 acres above the town where Spencer Park had been located.// Photo by Justin Tunis |

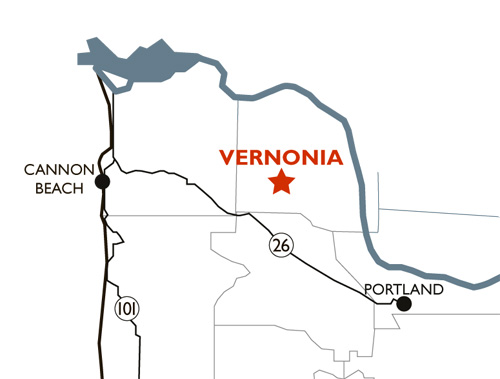

In the winter of 2007, a series of Pacific storms unleashed their fury on Vernonia, a small town in rural northwest Oregon that sits on the Nehalem River. The river crested seven feet above flood stage, and the ensuing flood swamped nearly half of Vernonia’s homes, one third of its downtown buildings, the town’s sewer and electric systems, community health clinic, senior center and food bank. The entire school district — elementary, middle and high schools along with the Head Start building — was left in ruins.

The damage to Vernonia’s property was estimated at $113 million. The damage to Vernonia’s soul was incalculable.

How could this tiny community survive such loss? There were some who believed it could not. But there were many more who believed this was exactly the moment — when Vernonia was on its knees — to re-invent this struggling town surrounded by lush forests, streams and parkland, and in those places plant a future.

Raise that wall

On a cool, rainy morning in late June, about 80 people — townspeople, local and state officials, Portland business leaders, philanthropists, teachers, and students — gathered on a hill overlooking the construction of Vernonia’s new $39.3 million K-12 school.

|

At the June wall-raising celebration, from left: Columbia County commissioner Tony Hyde, Portland businessman Tom Kelly, Northwest Natural community relations manager Von Summers, and Vernonia school superintendent Ken Cox.// Photo by Justin Tunis |

Getting to this day took Herculean efforts. The town had to identify a workable site out of the flood plain, navigate a rat’s nest of land-use and zoning regulations, upgrade roads and infrastructure, and find the money to begin. All this while painfully watching families, students, businesses and opportunity seep from the town. For three and a half years, the town held together its existing schools with band-aids and hope while the world moved on and largely forgot that Vernonia had almost been lost to the 2007 flood, the second — and more damaging — of two 500-year floods in 11 years.

“It’s a long time for people to be patient,” says Dan Brown, the town’s planning commission chair, flood recovery manager and owner of the downtown Grey Dawn Gallery.

But on this day, it was time to gather and celebrate the new 135,000-square-foot school taking shape on land 50 feet higher than where the current schools now sit.

As the construction crew worked below at the 32-acre site, kids gobbled donuts and townspeople and visiting dignitaries joined Vernonia school superintendent Ken Cox as he led the crowd in a whoop of “Raise that wall!” With that first wall it became certain that a new school — and a new idea about the town’s future — would open its doors next September. More than just a cool sustainable school being built to LEED platinum standards, this school is envisioned as a building block in the town’s economic future with ideas such as a natural resources curriculum, university partnerships, using locally purchased biomass, and training students and the community to be part of a green economy workforce — the hopeful triumph of the flywheel effect over the doom loop.

|

Above: The 2007 flood filled Washington Grade School’s basement with 39 inches of water.Below: Lockers were painted on the wall outside the gym after the high school was torn down. Students won’t park in the vacant lot where their high school used to be.// Photos by Justin Tunis |

|

|

“We are going to make the school the catalyst for our economic change forever more,” declared Tony Hyde, a Columbia County Commissioner, former logger and past mayor of Vernonia.

It is inarguable that this beauty of a school, with room for 1,000 students and abundant space for community use, will be far better than the flood-damaged, ragtag buildings it replaces. Every time it rains, anxious grade-schoolers ask if it will flood again. Since the flood, middle and high school students have been in temporary modular classrooms. “Three blocks from the band room to the classrooms with no cover,” says Cox. The class of 2012 will graduate next summer having never had a high school, much less simple things like lockers, save those painted on the walls outside the gym in memoriam. Since 2007, Vernonia’s population has dropped to 2,155, and the number of students has fallen from 697 two months before the flood to 590 this past June.

What is arguable is how much a school can jump-start the recovery of a town that faces formidable problems such as few local jobs, broken infrastructure and costly flood recovery. But to live in rural Oregon today takes equal parts hope, resiliency and sometimes a crazy notion of what is possible, so on this day in late June it was time to celebrate the potential.

Mike Pihl watched the walls come up. Pihl, who owns a logging company and sits on the city’s economic development committee, has four children in Vernonia schools. More famously, the 6-foot-4 Pihl has been on the History Channel’s reality show Ax Men for five seasons.

“If it wasn’t for this,” he observed, “you might as well wipe Vernonia off the map.”

Build it back better

Like other small towns across Oregon — across America — Vernonia struggles with higher unemployment and lower wages than urban areas, scarce capital, aging infrastructure, and the exodus of its youth. These problems have only deepened in the past several years with the recession and its lingering fallout. “We have to reinvent ourselves,” says Scott Laird, editor and publisher of Vernonia’s Voice, “because what we have isn’t working.”

|

School superintendent Ken Cox in the gym. High school and middle school students have been in temporary classrooms since 2007. “It didn’t make sense to rebuild where we were,” says Cox.// Photos by Justin Tunis |

|

But the town does have a Mayberry-esque charm; townspeople say it’s a safe place to raise kids; there’s freedom to roam. Situated in the Upper Nehalem Valley in the foothills of the Oregon Coast Range, it possesses exceptional natural beauty, and amenities such as the 21-mile Banks-Vernonia state trail built over an abandoned railroad, Stub Stewart state park and a mountain bike skills park next to Vernonia Lake. Tenacious, dedicated people make this their home.

Tony Hyde was in Portland in 2007 when the rains began and couldn’t get back to Vernonia to his family or his flooded home. He remembers talking to then-Gov. Ted Kulongoski, trying to think beyond just the raw recovery that would soon face the town, including having to move half of its homes, its schools and other public buildings outside the flood-risk area in the middle of town.

“Kulongoski asked me, ‘What does Vernonia look like in 20 years?’” Hyde remembers. That was a critical question. Vernonia once was a thriving timber town with more than 500 mill jobs until it was nearly wiped out in 1957 when the Oregon-American Lumber Company shuttered operations, its supply of big trees exhausted. Over the decades since, the town has fought to regain its footing, but never again attracted another anchor business.

The town had no chance without its schools. In 2008, Kulongoski designated rebuilding Vernonia’s schools an Oregon Solutions project, naming Hyde and Portland businessman Tom Kelly as co-chairs. Oregon Solutions, housed at Portland State University, is designed to cut red tape and build effective collaborations to tackle the state’s deepest problems.

The ambition was to not just rebuild the schools, but “build them back better,” hook them to the sustainability sizzle in the state and position them as part of the growing green economy. Sustainability would be the true north of the town’s reinvention. How could a former timber town find its way back through those same woods? If part of the answer was a green school that could help grow a local green economy, it might provide a beacon to other rural Oregon communities with aging schools and decimated economies. “We are not just putting a school back together,” says Hyde. “It’s about the future.”

The Oregon Solutions team marshaled resources and a coalition of local, state and federal officials. That included heavy-hitting Portland businesses such as The Standard and Northwest Natural and Portland leaders such as Ken Thrasher and Sho Dozono, along with Vernonia officials, citizens and businesspeople.

|

|

After a storm dumped nearly a foot of rain, the Nehalem River crested on the night of Dec. 3, 2007, at a height of 18.59 feet, seven feet above flood stage, swamping Vernonia.Photos: top by Scott Laird/ Vernonia’s Voice. Bottom by Jamie Jones |

During the depths of the recession in November 2009, voters of the Vernonia School District increased their property taxes by approving a $13 million school bond, a “down payment” on a new school that was then boosted by $16 million from federal and state sources, including $11 million from FEMA.

Then many others began putting their chips on Vernonia, including $76,000 from several timber companies, $100,000 from Northwest Natural, $1,000 each from the cities of Nehalem and Maupin, gifts from individuals such as Gun Denhart of Hanna Andersson and Anne Kilkenny of the Winks Hardware family, who gave $50,000. About $38,000 has been raised from community fundraisers, and $1.2 million has come from half a dozen foundations. To date, $31 million has been committed to the school rebuilding.

“When we went to see the editorial board of The Oregonian, we were all pretty nervous,” says state Sen. Betsy Johnson, whose district includes Vernonia. “They asked, ‘Who cares about Vernonia?’ and Tom Kelly practically came up out of his chair,” Johnson remembers with relish. The newspaper subsequently wrote several editorials supporting Vernonia.

Kelly, president of the remodeling company Neil Kelly and also co-chair with Johnson of the campaign committee for the school, was worried fundraising would fall flat. “But it has a story that pulls at people’s heartstrings,” he says. “And I’ve been really impressed with how many people in the Portland business community have helped out.”

“If we cross off Vernonia, we might as well shut down 45 other towns across Oregon,” says Justin Delaney, a vice president at The Standard and member of the campaign committee. “There was no way Vernonia could raise this money by themselves.”

|

Blue Heron apartment residents were evacuated; Washington Grade School is in the background. School supplies and books were destroyed.Photos: top by Jamie Jones, bottom by Scott Laird/Vernonia’s Voice |

The Roseburg-based Ford Family Foundation, which was founded by the Ford timber family, broke from its normal funding rules to signal its strong support for Vernonia and made a $1 million challenge grant. The town’s leadership had participated in the training program at the Ford Institute for Community Building and as the disaster was unfolding, those alums were rallying to pull the town together, says foundation president Norman Smith.

“We don’t build schools,” says Smith. “This case was entirely the exception. This is about building a new community around its intrinsic assets.”

And, as Hyde points out, those assets include the 1 million acres of private timber land in Columbia County, where in 2010, 123 million board feet of timber were harvested. “You can’t ignore that,” he says. “You can’t say timber is no longer an economic issue.”

In 2009, there was a national promise to build a green economy, and the color of money was green. There were opportunities for state and federal funding for projects that involved sustainable energy and other ideas and the Vernonia team pounced on them, tying the ideas in with the school, such as a biomass boiler that would be fed by local wood products and a focus on a natural resources curriculum. The Pinchot Institute, a national conservation group, got involved, helping develop biomass ideas and a pilot program linking the health of residents and forests. (See page 38.) The vision would further build on Vernonia’s historic and cultural connections to its forests.

Reconnecting Vernonia’s economy to its natural resources “was an idea waiting to happen, but it needed a place and a time,” says Hyde.

The place and time arrived with the destruction of its schools.

Making it green

|

RIGHT: Dan and Heidi Brown own the Grey Dawn Gallery in downtown Vernonia. Dan is also the flood recovery manager and chair of the planning commission and Heidi is the schools’ nurse.BELOW: Brad Curtis owns Photo Solutions. He’s unsure he can continue to do business in Vernonia.// Photos by Justin Tunis |

|

On a basic economic level, the school district means jobs; with about 85 employees, it’s the town’s largest employer. And a better school would attract more families and students. But beyond that, how to position the schools to be a bigger boost to the economy?

“The question was always, ‘What’s the economic future of the town?”’ says Alissa Keny-Guyer, Oregon Solutions’ program manager.

To answer that, in its 2010 strategic plan the city looked 20 years into the future and imagined that the new LEED platinum K-12 school had been a catalyst for the town’s improvement. It was now the “Bicycle Center of Oregon,” where Stub Stewart state park was connected to a thriving downtown frequented by residents and tourists, drawn by its parks and outdoor recreation. It was a town where the idea of being a “living laboratory for the natural resource economy” had become a reality and produced real, local jobs, a town where new light industry finally gained a foothold.

Two of the central ideas on how to connect the new school to a new green economy are a natural resources curriculum integrated into all subject areas for K-12 students — many of whom come from logging families — and the Vernonia Rural Sustainability Center, a set of programs — a strategy — that aims among other activities to incubate green entrepreneurs and new natural resource businesses, provide workforce training and apprenticeships for students and the community, and build relationships with research institutions.

“It’s an interesting idea with a lot of potential,” says Bruce Weber, director of Oregon State University’s rural studies program. Vernonia is in the right location for this, and “they have some visionary people. Urban people are interested in sustainability and going to Vernonia is not a big trip. If urban institutions could set up learning opportunities there, I think it could work.”

The green curriculum has been supported by $25,000 from Oregon Fish and Wildlife for salmon projects and training, donations from Big Horn Logging and Longview Timber, $10,000 from the Department of Education for teacher training, and help from the Oregon Natural Resources Educational Program. Such a curriculum is meant to prepare Vernonia students for “jobs of the future” in areas such as forestry, natural resource research and engineering design.

Vernonia schools struggle; scores for reading, math and writing generally have been below the state average. It is also a district where 40% of the students live at or below the poverty level. Along with this, a bruising economy has cut state school dollars, eliminating teachers and programs: The elementary school no longer has music; kindergarten has been cut to halftime; the middle school lost its principal and counselor, the high school its full-time athletic director.

But Vernonia also produces extraordinary students. Katy Stevens was a sophomore when the flood destroyed her home. She “lived all over the place” while finishing high school. “We didn’t have a lot of books, no labs. We didn’t have a gym for a while. Oh, god. I would have loved to have had lockers,” she says. “But at the same time, all these challenges just drove me harder toward college. It was inspirational in a way. I saw all these people working hard to make life normal. If everything had been really easy, I don’t think I would be where I am today.”

Despite the disadvantages, the 19-year-old Stevens is now on a four-year scholarship at the University of Portland and is majoring in both social work and psychology, turning the flood trauma into triumph. “I want to work with displaced families, orphans, foster kids,” she says. “Homeless people, like I once was.”

The new curriculum and the rural sustainability program are meant to lift overall student achievement, and also benefit college-bound students. “I see our high school kids working with college and professional people,” says Aaron Miller, the principal of Washington and Mist elementary schools and the coordinator of both efforts. “I see us being a leader in natural resources research.”

The new curriculum and the rural sustainability program are meant to lift overall student achievement, and also benefit college-bound students. “I see our high school kids working with college and professional people,” says Aaron Miller, the principal of Washington and Mist elementary schools and the coordinator of both efforts. “I see us being a leader in natural resources research.”

The rural sustainability program originally was to be housed in a separate building next to the new school, which would include high school science labs and space for research partners, and be a magnet for tourism and green-minded industries.

But in May, P&C Construction said cost increases had pushed the project to $42 million and the $2.8 million stand-alone center was cut. “I’ve been pushing really hard that we deconstruct the Washington grade school and use those materials for a center because it really walks the walk,” says Hyde.

“The new campus and the whole community have become the rural sustainability center,” says an equally undaunted Miller, whose son is a senior at Vernonia High and daughter a recent graduate. “We have miles of linear park, all these rivers and streams, several outdoors schools. Every single part of our natural surroundings can be our classroom.”

The school district so far has partnered with the Upper Nehalem Watershed Council on stream restoration projects and is working with Oregon Fish and Wildlife on fish programs. A Bureau of Land Management nursery in Molalla plans to relocate to the new school, and the district wants to create a native plant nursery and garden.

Some partnership building with universities has started: OSU’s extension service has helped with the natural resources curriculum, and its rural studies program will track the school’s impact as part of a Vital Vernonia study. PSU’s Institute for Sustainable Solutions planned to develop classes using Vernonia as a case study, but that has stalled.

“There are some areas where we’ve taken some baby steps, and some giant steps,” says Miller. “University partnerships are baby steps. The No. 1 thing is our K-12 education.”

Two steps forward, one step back. It’s a ratio that can look pretty good to a town like Vernonia.

Beyond the school

As vital as a new school is and as innovative as the green economy ideas are, they alone cannot resolve the challenges to Vernonia’s recovery: a commuter workforce, a critical shortage of light industrial and commercial land, a shrinking tax base, inadequate broadband access, costly water rates, a wastewater system that will cost $9 million to repair — issues that can be sure-fire business killers.

|

Vernonia has small-town charm and townspeople say it’s a safe place to raise children. Downtown businesses hang on despite the bruising economy that has claimed about nine shops.// Photos by Justin Tunis |

|

“The No. 1 issue was to get the school built for sheer survival’s sake,” says businessman Brad Curtis. “We’re all very proud. But you are really just buying time with the school.”

Recent political turmoil also has delayed traction on recovery efforts. Over the summer, voters recalled three of the five city councilors who had fired interim city administrator Bill Haack because he had helped with the investigation of police Sgt. Michael Kay, who eventually was let go for misconduct. Vernonia has had about seven city managers in eight years.

“The city has stopped,” says Randy Parrow, a city councilor and co-owner of the Sentry supermarket, the sole grocery in town. “We’ve spent six months fighting among ourselves instead of taking care of business,” says publisher Scott Laird. “There’s not a lot happening on economic recovery. People are just trying to keep their head above water.” (In early September, a reconstituted council rehired Haack as city administrator.)

Between the flood and the recession, about nine shops have closed in the small, sagging downtown, including a nursery, several restaurants, a bike rental shop and a hair salon. Dan Brown, the flood recovery manager, estimates that 10% to 20% of the homes slated for flood help are being lost to foreclosures, including eight homes in just three blocks on A Street. About 42 homes have been or are slated to be demolished.

“Vernonia has been through an awful lot and it shows,” says Sen. Betsy Johnson.

Lack of funding has stalled the Rose Avenue Project, a $3 million social service “hub” to house the nonprofit health clinic, senior center and food bank that were wiped out in the flood. Proposed along with the 25,000-square-foot hub is a biomass boiler that would use local biomass to heat the hub and provide energy for nearby buildings, a project that has received federal seed money.

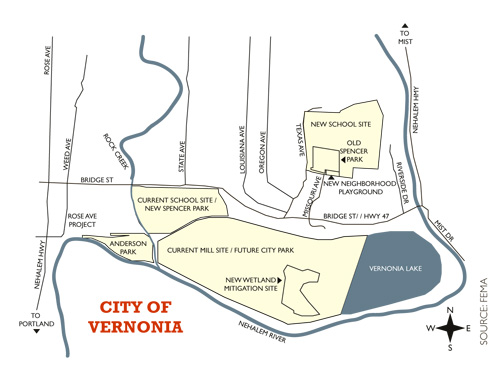

Perhaps most critically, the city lost its core business land when new FEMA maps were redrawn after the flood; 177 acres of current school and business acreage will be rezoned to parkland. The future plan for those acres includes replacing Spencer Park, where the new school is sited, and one day building other amenities, such as biking, hiking and wildlife viewing areas.

This leaves no zoning that allows for a business park within the city limits. In the short term, the city hopes to rezone 12 acres of land above the new school for green industrial, which could take up to two years. The city is trying to find and acquire land for light industrial and commercial use, but expanding its growth boundary is an arduous chess game that could take many more years to complete. “Right now, if a business wanted to come in there’s no place for them,” says Sharon Bernal, a local realtor and chair of the economic development committee.

This deeply hurts the town’s ability to attract businesses, and keep what it has. Brad Curtis started Photo Solutions in 1989, a microlithography and glass-machining company with 10 employees. Curtis, who is also on the economic development committee, has lived in Vernonia for 22 years and wonders if he can hang on.

He must move his business out of the flood plain, but there is no light industrial site to build on, and no suitable place to lease. “So do we figure out a way to hang tight and stay here and forego growth,” he asks, “or do we move into Washington County? It’s hard to make a business case to stay in this town right now.”

Losing even 10 local jobs would be a blow to a town where it’s estimated that as many as 90% of its working residents leave each day to make the 45-minute drive for jobs in Beaverton, Hillsboro or Portland, dropping their shopping dollars in those cities instead of in Vernonia. “In reality, we are a bedroom community,” says Heidi Brown of Grey Dawn Gallery, which opened in 2000; Heidi and Dan’s two children are fourth-generation Vernonians. “[Commuters] get tired of the drive and move back out. And we’re not a cheap place to live.”

|

Above: Every summer the town creates an old-fashioned swimming hole by damming up Rock Creek, which runs through the center of town.Below: (Left to right) Keaton Simmons and brothers Bryce and Adrian Archer at the swimming hole this summer.// Photos by Justin Tunis |

|

“When I look at [the future] right now, I don’t see how people can ‘evacuate’ the town every day if gas is $4 to $5 a gallon,” says Curtis, who transferred his eighth-grader to a Beaverton school after the flood. “The school might attract a few people, but you’ve got to supply jobs out here.”

One bit of progress is the recently approved rezoning of 27 acres of land owned by Tim and Michelle Bero from forest to light industrial; the land is adjacent to the runway at Vernonia Municipal Airport, outside the city’s growth boundary.

Tim Bero, a plainspoken businessman who is on the economic development committee, estimates he spent a quarter of a million dollars to get his property rezoned after a protracted battle. He wants to attract companies from Vernonia along with new industries to the airport. His goal is to create at least 30 jobs and he’s giving it five years, even though “my wife is fed up.” The Beros own Technetwork and TNW Firearms, a gun reproduction business with $2 million in revenue. They moved to Vernonia 20 years ago after Bero closed his Silicon Valley robotics company. They also transferred their children out of the school district.

But Bero still has fight in him despite the costly rezoning fight, and asks the ubiquitous question: “We are living in the carcass of what the town was supposed to be. So what do we do to fix that?”

Bero is betting on bringing in business because he doesn’t believe the answer is tourism: “The weather sucks.” Randy Parrow disagrees: “Tourism is all we have to offer.” Scott Laird sees diversity as the key: “Little things make a big difference in a small town. So economic recovery will be small things that happen in small ways.”

“A lot of our internal unrest is fear,” says Dan Brown, pointing out that “we can’t even afford to run the street sweeper, and we’re down to two police officers.”

“The one thing that everyone agrees on is the school,” he says. “This school is a great beacon of hope.”

A step forward

Weary town leaders up to their elbows in the muck of recovery find it hard to see the future, but those a few steps back imagine it clearly.

“I can see this town being like Hood River,” says Tom Kelly.

“Things in Astoria are good,” says Betsy Johnson. “The same possibility is there for Vernonia.”

Other rural Oregon towns have dug themselves out of deep holes by building on their ready-made or created assets: Cannon Beach and its art scene; Baker City and its mass of beautiful turn-of-the-century buildings; Hood River and its recreational amenities and high-tech jobs; The Dalles and its success in business development and remaking its downtown; and Astoria, which turned itself from a gritty, rundown former logging and fishing town into a place where Microsoft executives snap up Victorians and you can buy a cup of hand-roasted organic coffee to go with your artisan sandwich. Why not a green school and green economy as a shovel?

|

Sharon Bernal, part of a longtime timber family and chair of the economic planning committee.// Photo by Justin Tunis |

“I believe there is a huge draw of people who want to go green,” says Sharon Bernal, the economic development chair. “What I envision is a lot of small, in-home business owners who are going to want their children in this school. Also, the [rural sustainability] center is huge. When you put those two things together, I think we can see a lot of people who have their kids in private schools in the city moving to this community.”

The story of the little town that could is compelling, and many are pulling for it.

“When you think of it as a needful community, it is hard not to think of all the other needs,” says Alissa Keny-Guyer of Oregon Solutions, which will remain through the fundraising phase of the Vernonia project, a first for the organization. “But if you think of Vernonia as a transformational community, it presents a lot of different models for how rural Oregon can survive in the 21st century.”

To get there, fundraisers will face foundations that usually don’t invest in brick and mortar, and a tough economy as they search for the remaining $8 million needed for the school; that doesn’t include the approximately $3 million it will take to build a new football stadium and other athletic fields. “I can’t give you a roadmap to where every dime will come from,” Johnson says, “but it’s there and we’re going to go find it.”

“And there are a lot of people who aren’t aware that this hasn’t been fixed yet,” says Eric Friedenwald-Fishman, president of the Metropolitan Group, which is advising the fundraising. “Four years is a long time.”

As Dan Brown said, it’s a long time to be patient. So many things are unknowable and uncertain about the town’s future, and about how a school might be its economic catalyst. The green economy in Oregon and the nation is wobbly. Like other communities that have faced this juncture, there’s a fair amount of making it up as you go along. Magical thinking is not uncommon.

But one thing is certain.

Next September, a new green K-12 school will open, running on local biomass, partnering with universities and focused on studies relevant to its rural students, students who will have honest-to-god lockers, not just ones painted on walls. It can pour buckets and principal Aaron Miller will not have to empty them. Businessman Brad Curtis might even bring back his son to be part of the first high school graduating class.

On that day next September, the community will step forward. A community where residents in struggling rural towns like Oakridge or Burns might one day look to and say, “I can see this town being like Vernonia.”

Robin Doussard is the editor of Oregon Business. Contact: [email protected]

Sustainable Features

Vernonia’s new $39.3 million K-12 school, designed by Boora Architects of Portland, is being built to achieve a LEED platinum rating. Modeling shows that the school’s green features will save the school district $70,000 per year in energy costs compared with the existing schools. The integrated single building is more space and energy efficient than three schools, and maintenance costs will be less. The building aims to achieve a 45% energy savings over a baseline, code-compliant building. Other green features include:

Vernonia’s new $39.3 million K-12 school, designed by Boora Architects of Portland, is being built to achieve a LEED platinum rating. Modeling shows that the school’s green features will save the school district $70,000 per year in energy costs compared with the existing schools. The integrated single building is more space and energy efficient than three schools, and maintenance costs will be less. The building aims to achieve a 45% energy savings over a baseline, code-compliant building. Other green features include:

- A central wood-based thermal energy system. The school will use about 370 green tons of local woody biomass annually from six regional sawmills to produce the pellet supply to service the boiler system. The pellets will be produced by West Oregon Wood Products at one of its two facilities in Banks and Columbia City. The hope is that the school’s biomass system along with the Rose Avenue biomass energy project and more residential pellet use would eventually provide enough local demand to create a pellet production plant in Vernonia, thus creating local jobs.

- Siting to take advantage of solar orientation and prevailing winds

- Daylighting to minimize the use of electric light

- A ductless boiler system that will heat radiant floors

- A highly insulated building envelope for heat efficiency

Community Space

About 40% of the school’s 135,000 square feet will be for community use, including:

- The high school and elementary school gyms for sports, public meetings, performances, and temporary housing for 300 in emergencies; the school will serve as an emergency community facility with a backup generator

- Weight and fitness rooms

- Wood and metal shop and art studio for adult education, workshops

- Library, media center, two computer labs for distance learning, classes

- The Commons area, Black Box Theater and the Amphitheater for performances, lectures, exhibits

Sources: The Metropolitan Group, Aadland Evans Constructors

Timeline

Mill workers with a harvested tree in the late 1920s |

|

2007 floodwaters inundated the basement of Washington Grade School. |

|

Third-grade drawings of the 2007 flood were funny and heartbreaking. |

|

Vernonia school superintendent Ken Cox at the wall raising. |

|

The new $39.3 million K-12 school is being built to achieve a LEED platinum rating for energy efficiency. |

1891: Vernonia is incorporated

1922: Railroad arrives

1923: Oregon-American electric-

powered lumber mill completed

1930: Washington Grade School opens

1953: Vernonia High School opens

1957: O-A mill closes

1996: 500-year flood hits Vernonia on Feb. 8

2005: Vernonia Middle School opens

2007: second 500-year flood hits on Dec. 3

2008:

APRIL: Vernonia schools designated an

Oregon Solutions project

SEPTEMBER: high school demolished; middle/high school students move to modular classrooms

2009:

FEBRUARY: site chosen for new school

APRIL: land-use process begins on new school site; finishes in just eight months

NOVEMBER: school bond passes with more than 61% of the vote, with a 68% turnout

2010:

JANUARY/FEBRUARY: Vernonia Rural Sustainability committee launched

FEBRUARY: NW Natural makes $100,000 donation

APRIL: Oregon Dept. of Energy awards $1.1 million for green energy projects

JUNE: private campaign committee launched

AUGUST: Vernonia holds its “biggest school reunion”

DECEMBER: new school breaks ground; ODOT awards $3.8 million for transportation/access projects

2011:

JANUARY: $11.2 million FEMA award announced

JUNE: first wall is raised on new school

FALL: community fundraising begins

2012: new K-12 school is set to open in September

Sources: City of Vernonia, Oregon Solutions, Vernonia Pioneer Museum Association’s Vernonia

By the numbers

2,155

population in 2011

2,311

population in 2009

160

business permits issued in 2010

180

business permits issued in 2007

366

households with children in school

43

average inches of annual rainfall

32

median age

8

city and state parks

$41,181

median household income in 2000

$113 million

damage estimate from 2007 flood

Sources: U.S. Census, City of Vernonia

Linking: forests, energy and health care

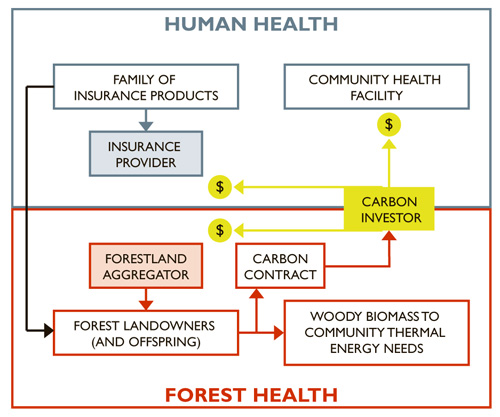

One of the most innovative partnerships to emerge from the Vernonia school project, and another one of those “right place at the right time” moments, is with the Pinchot Institute for Conservation, a forest conservation think tank based in Washington, D.C.

Catherine Mater, a senior fellow with the Pinchot Institute and president of Mater Engineering in Corvallis, was a member of the Oregon Way advisory group when the Vernonia Oregon Solutions team approached it seeking federal stimulus money for the new school.

Mater had been involved in studying for several years the issue of rural forest owners selling off their land to pay for unexpected health-care expenses. “I noticed they were surrounded by lush forestland, and didn’t have any biomass ideas. So I told them about this other idea,” says Mater.

From that has come the idea for a “thermal energy center” that would heat the Rose Avenue social services hub using local wood biomass — the new K-12 school is also to be heated by a similar biomass system — and the Western Oregon-Vernonia Forest Health/Human Health Initiative, a pilot project that Mater says is the first of its kind in the U.S. The pilot project is evaluating how to pay landowners for not selling or developing their property in exchange for carbon credits that they could sell to get health insurance; 20% of the proceeds would fund Vernonia’s community health clinic, which would then contract with local landowners for biomass for the thermal energy center. Pinchot says there are 700 private non-industrial forestland owners in Columbia County.

“It will fundamentally change the way we manage our forests, the way we finance health care and the way we handle health care for our families,” says Mater.

Funding has come from the Kelley Family Foundation, Pinchot, $50,000 from the USDA, and Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon.

In early September, Pinchot and forest scientists from Oregon State University tested in Vernonia a new ground-based light detection and ranging technology to evaluate cost-effectiveness to measures biomass and carbon volumes, necessary when paying landowners for their forests’ carbon storage. In mid-September, interviews with Vernonia and area forest owners and their children showed enough interest in the idea to move forward with a business plan finalization. American Carbon Registry was selected to serve as the global carbon verifiers. Woodlands Carbon will serve as the lead state carbon developer, and L&C Carbon will help guide the Vernonia project. Next steps include finalizing carbon contracts with Columbia County landowners, securing a lead health-care sector carbon buyer, and securing the organization that will administer carbon deposits into landowner health-care debit cards.

Local realtor Sharon Bernal, Vernonia’s economic development chair, is one of those local timber families. Her great-grandfather homesteaded 160 acres in Vernonia; her grandfather bought 300 acres in 1932, and then gave 150 acres to Bernal’s father. Bernal, who has two adult sons, will inherit about 80 acres. She pays $629 a month for health insurance, so health care costs worry her.

“I’m getting a lot more involved with Mater and want to understand it before my dad passes because it’s important to me to keep that land,” says Bernal, whose father and landowner uncle do not support the idea. “We don’t want to sell.”

Robin Doussard