The tacky strip retail malls are dying, leaving behind a museum of failure.

The tacky strip retail malls are dying, leaving behind a museum of failure.

Story by Ben Jacklet // Photos by Adam Bacher

Follow McLoughlin Boulevard south out of Portland, past the gentleman’s club with the $5 steak special and the sprawling vacant lot next door, and you can get a wide-angle view of the reality of arterial strip development as it is. The 4.5-mile stretch of state highway from Milwaukie to Oregon City is a random mix of the weird, the cheap and the ugly: a restaurant with a bomber plane parked out front, a replica of the Statue of Liberty, a rectangular mountain of storage space, a huge “no-credit, no-problem” auto lot, a motel next door to a strip club with rooms starting at $29 per night, a 66,000-square-foot former GI Joe’s sporting goods store available, for sale or lease.

Follow McLoughlin Boulevard south out of Portland, past the gentleman’s club with the $5 steak special and the sprawling vacant lot next door, and you can get a wide-angle view of the reality of arterial strip development as it is. The 4.5-mile stretch of state highway from Milwaukie to Oregon City is a random mix of the weird, the cheap and the ugly: a restaurant with a bomber plane parked out front, a replica of the Statue of Liberty, a rectangular mountain of storage space, a huge “no-credit, no-problem” auto lot, a motel next door to a strip club with rooms starting at $29 per night, a 66,000-square-foot former GI Joe’s sporting goods store available, for sale or lease.

In the middle of this urban planning disaster is a strip mall with twin turrets built from residential-style brick, the Green Castle Retail Center. The buildings are attractive enough to stand out in a sea of hastily constructed eyesores, but the attempt at transformation they represent is daunting. Property owner Joe Green III says he and his father invested in the area and fixed up the property on the belief that “McLoughlin only has one direction to go, and that’s up.”

Not far from the Green Castle, plans are being made for a new light rail station. With light rail could come transit-oriented development, mixed-use density. A team of consultants is making plans for a more coherent future. But the gap is vast between Oregon’s urban planning ideals and the current realities on McLoughlin and other suburban-style strips from Beaverton to Salem to Medford.

Even with its vaunted land use laws, Oregon is no stranger to strip mall sprawl. Metropolitan Portland contains over 400 miles of arterial commercial strips heavily laden with every variety of retail space. Head west out Canyon Road to Beaverton, south along 99W from Tigard to McMinnville, or east along Powell Boulevard from 82nd Avenue to Gresham, and you might just as well be touring the suburbs of Atlanta or Indianapolis: huge parking lots, congested intersections, national chain stores squeezing out any semblance of regional identity.

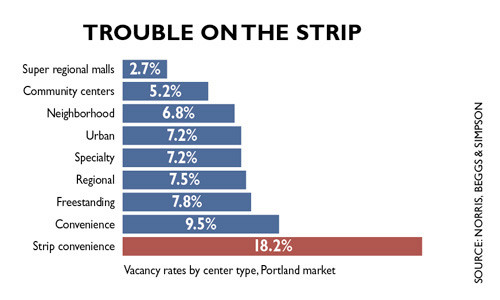

These areas fit the profile of convenience-driven strip development in that they are auto-oriented, endless and, well, ugly. They are also increasingly distressed. The latest in-depth retail report from Portland-based Norris Beggs & Simpson finds a steadily improving overall retail vacancy rate of 6.3% for the Portland market (significantly lower than the national rate of 7.2%), with major improvements in central city, neighborhood and regional shopping centers. The most troubled sub-category by far is “strip convenience,” with a vacancy rate of 18.2%.

Nationally, the Wall Street Journal has reported that strip mall vacancies continued to rise even after the recession ended. Locally, the picture is mixed. “If you have a grocery-anchored center you’re OK, because people still need to eat,” says J.J. Unger, a retail specialist for Norris, Beggs & Simpson. “But if you’re in a center that wasn’t designed properly, that doesn’t have an anchor, those are the guys having issues.”

Of course, it isn’t easy to categorize strip malls in the constantly changing world of retail sales. Is the Zupan’s Market at the corner of NW 23rd and Burnside a strip mall? What about the former auto lot on Northeast Sandy that is now a vintage clothing store with space for food carts? How many of the 12.5 million square feet of retail centers in the Portland market listed as “community centers” might be better described as strip malls?

Edward T. McMahon of the Urban Land Institute defines a commercial strip as “a linear pattern of retail businesses strung along major roadways characterized by massive parking lots, big signs, boxlike buildings and a total dependence on automobiles for access and circulation.”

Edward T. McMahon of the Urban Land Institute defines a commercial strip as “a linear pattern of retail businesses strung along major roadways characterized by massive parking lots, big signs, boxlike buildings and a total dependence on automobiles for access and circulation.”

McMahon is the author of a recent influential essay, “The Future of the Strip,” that argues persuasively that the era of strip development in the U.S. is “slowly coming to an end.” He builds his case on several large trends that he sees as irreversible:

- Developers have overbuilt the strip.

- Major retailers such as Target, Home Depot and even Wal-Mart are moving into the city.

- The suburbs are growing more urban.

- Younger shoppers want character and style.

- Gas prices and congestion make the strip even less enjoyable for shoppers.

- E-commerce will result in fewer and smaller stores.

In McMahon’s view, those trends add up to a powerful force that retailers and communities would be foolish to ignore. “The two distinguishing characteristics of strip malls are that they’re ugly and congested,” he says. “Try running a marketing campaign around that: ‘Shop here! We’re ugly AND congested!’”

Strip centers fitting that description were not built with legacy in mind. “Strip centers can live as short of a life as 10-12 years,” says Portland-based retail consultant David Leland. “Once they’re dead, they’re dead. You get two or three of them in a row and you’ve got a dead zone. You keep getting these newer, nicer centers further from the center, leap-frogging one another, and they leave behind a kind of museum of failure.”

Even professionals with a stake in the future of McLoughlin are blunt in acknowledging that the strip isn’t working. “You go into a lot of these places and look around and you know why they’re vacant,” Joe Green III says of his less-than-proactive neighbors near the Green Castle. “The traditional strip retail centers, they’re over — they’re done. And they should be.”

Commercial Realty Advisors broker Alex MacLean, who is trying to lease the massive space left behind on McLoughlin by the shuttered Joe’s store, says McLoughlin suffers from a lack of identity. “There’s nothing about that area that distinguishes it, with the possible exception of the auto lots.”

The same weakness applies to other struggling strips from Salem to Beaverton to Vancouver. Michele Reeves, a land-use consultant who works with communities to make better use of their commercial strips, says many of the problems result from poor planning and design. The proliferation of retail choices makes the strip congested, and cities respond by making the street even wider. Before long you have a blighted arterial where crossing the street is an act of valor. “What do you do? Keep widening the road? In 15 or 20 years you are going to have a 12-lane road, and it will still be congested.”

In her previous career, Reeves helped turn Portland’s North Mississippi Avenue from a run-down strip into a shopping and dining destination. Now she works with communities with sprawl problems to help make their commercial strips more functional and appealing. “We’re in the middle of a big demographic shift,” she says. “People want to live in the center, in walkable neighborhoods. For communities with no walkable amenities, they need to worry because they are on the wrong side of the trend.”

Plenty of communities are aware of the trend in Oregon, and quite a few are acting on it, through Main Street investments and various attempts at urban revitalization. There is even a McLoughlin Area Plan Committee trying to capitalize on the coming light rail line to build a more attractive, modern retail district, with a sense of place and character rather than a blur of roadside signs.

“The next 30-40 years will be the era of the reinvention of the suburbs,” predicts the Land Institute’s McMahon in a telephone interview. “The development paradigm is changing and the economic recession speeded up a bunch of things that were happening anyhow.”

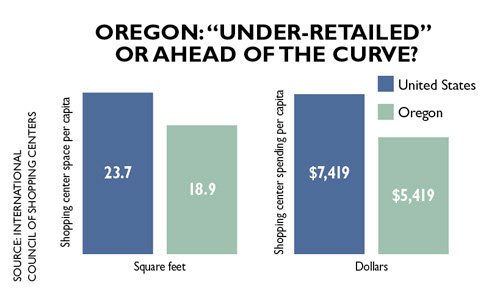

By national standards, Oregon is considered “under-retailed,” with 18.9 square feet of shopping center space per capita compared to the national average of 23.7 square feet. There are two major reasons for this. The state’s tougher-than-average land-use laws slow the spread of retail-friendly sprawl, and the lack of a sales tax limits the government’s incentive to rubber-stamp all retail requests in order to bring in more tax revenues.

But while Oregon’s 19 feet of shopping centers per person is low by U.S. standards, it is enormous compared to France and other nations that have embraced buying locally over chains. The average in most of Europe and Canada is closer to 2 square feet per capita.

But while Oregon’s 19 feet of shopping centers per person is low by U.S. standards, it is enormous compared to France and other nations that have embraced buying locally over chains. The average in most of Europe and Canada is closer to 2 square feet per capita.

For communities already defined by blighted commercial strips, the notion of becoming more like Paris is more than slightly complex. “You don’t solve this puzzle easily,” says Reeves. “It’s expensive and there’s not a lot of money out there.”

Further complicating matters is the fact that, as much as urban planners and retail consultants hate them, commercial strips kind of work. About 35,000 people drive up and down McLoughlin each day, and enough of them stop in to buy a car or a pawned guitar or a lap dance to keep those businesses open. Rents are low compared to the rest of the Portland area, and that’s not a bad thing for everyone.

“These areas do provide low-cost space,” points out Jerry Johnson of Portland-based real estate consultancy Johnson Reid. “Certain businesses are great businesses but only if they have low-cost space.”

Robert Bach, chief economist for California-based real estate firm Grubb & Ellis, argues that reports of the commercial strip’s death have been greatly exaggerated. “Strip centers are based on convenience,” he says, “and there will always be some demand for what they offer.”

Portland landlord Barry Menashe, who owns property in suburban strips in Beaverton and Gresham as well as downtown, also scoffs at the argument that commercial strips are doomed. “There’s still cars, neighborhoods, people, customers. They aren’t just going to go away.”

He has a point. But can commercial strips make the changes necessary to remain competitive? In some ways and in some areas, they already have. For one thing, strip centers are becoming more ethnically diverse. One fully packed center along Highway 99W, the Tigard Plaza, contains a fish and chips joint, a Chinese seafood market, an Italian Deli, an Indian imports store, a Vietnamese beef noodle soup house, an Asian grocery store, a pizza place, a Mexican tienda with fresh bread and money wiring services, a driving school, a tattoo and body-piercing shop, a co-ed fitness center, a barber shop and more.

He has a point. But can commercial strips make the changes necessary to remain competitive? In some ways and in some areas, they already have. For one thing, strip centers are becoming more ethnically diverse. One fully packed center along Highway 99W, the Tigard Plaza, contains a fish and chips joint, a Chinese seafood market, an Italian Deli, an Indian imports store, a Vietnamese beef noodle soup house, an Asian grocery store, a pizza place, a Mexican tienda with fresh bread and money wiring services, a driving school, a tattoo and body-piercing shop, a co-ed fitness center, a barber shop and more.

The same low rent that enables a no-credit used car lot to survive also allows ethnic Chinese herb shops and bilingual beauty centers to take hold. The most prosperous example of diversity on a local strip may be the Fubonn Shopping Center on 82nd Avenue, billed “the largest Asian shopping center in Oregon.” Completed in 2005, Fubonn has transformed a formerly bland strip location into a lively collection of coffee houses and bubble tea shops, Vietnamese restaurants and shops selling books, music and jewelry. Just down 82nd on the opposite side of the street from Fubonn, a huge former multiplex theater has been transformed into a Slavic church.

The strip mall is also becoming more local. Popular Oregon retailers and eateries such as New Seasons Market, Powell’s Books, McMenamins brew pubs, Pastini Pastaria and Café Yumm have found their way into suburban strips long dominated by Home Depot, Old Navy and other national chains. And strip-style locations throughout close-in Portland have adapted to welcome brewpubs, food carts and indie clothing stores.

Even some McLoughlin-like strips along state highways from Ashland to Lake Oswego have been redesigned to improve neighborhood ambience. Successful examples range from Siskiyou Boulevard in Ashland to State Street in Lake Oswego and Macadam Avenue in Southwest Portland.

Even some McLoughlin-like strips along state highways from Ashland to Lake Oswego have been redesigned to improve neighborhood ambience. Successful examples range from Siskiyou Boulevard in Ashland to State Street in Lake Oswego and Macadam Avenue in Southwest Portland.

But as popular as these small adaptations may be in certain neighborhoods, they do little to reverse the powerful trend of shoppers abandoning older strips in favor of newer destination shopping centers further away from the city center. Popular malls such as Bridgeport Village in Tigard and Tualatin, completed in May 2005, adapted early to the consumer demand for amenities that go beyond the usual endless sea of parking lots, and as a result they held up much better during the recession than their older competitors.

“It’s not just about demographics anymore,” says Fatima Al-Dahwi, a retail project manager with Portland-based Leland Consulting Group. “It’s about creating a place where people want to spend time. One of the products of the economic downturn is that retailers are very focused on experience enhancement online. We’ve gotten away from the Field of Dreams model — ‘Build it and they will come.’ You’ve got to engage shoppers.”

That’s what Gramor Development president Barry Cain is trying to do at his soon-to-be-completed Progress Ridge TownSquare in Beaverton, a $60 million investment. Cain has been developing retail centers in Oregon and Southwest Washington for 26 years, with more than 60 centers in the Gramor portfolio. As tastes have changed he has shifted from big-box malls to compact, walkable centers such as Lakeview Village in Lake Oswego. His latest Fred Meyer, due to open in Wilsonville in July, features landscaped sidewalks, fountains and an amphitheater.

At Progress Ridge, construction workers from R&O Construction are busily sculpting a 110-acre former rock quarry into a modern version of the age-old town square, with outdoor fountains and eating areas, a 24-hour coffee shop, a local hardware store instead of a Home Depot, an outdoor fireplace, a pond with a floating dock, a row of small service businesses next door to the outdoor seating in front of the cinema, all overlooking a wine-tasting garden with a planted vineyard. The center, due to open by September, has three anchor tenants, and not one is a national chain. Instead Cain has signed on New Seasons Market of Portland, Big Al’s Family Entertainment Center of Vancouver, Wash. and Cinetopia Theaters, also of Vancouver.

At Progress Ridge, construction workers from R&O Construction are busily sculpting a 110-acre former rock quarry into a modern version of the age-old town square, with outdoor fountains and eating areas, a 24-hour coffee shop, a local hardware store instead of a Home Depot, an outdoor fireplace, a pond with a floating dock, a row of small service businesses next door to the outdoor seating in front of the cinema, all overlooking a wine-tasting garden with a planted vineyard. The center, due to open by September, has three anchor tenants, and not one is a national chain. Instead Cain has signed on New Seasons Market of Portland, Big Al’s Family Entertainment Center of Vancouver, Wash. and Cinetopia Theaters, also of Vancouver.

Cain estimates that the new center will employ more than 800 people. It is the largest retail project in Oregon since the recession hit and the most complex project Gramor has done.

It took persistence to put the project together. Between the struggles to gain approval from city planners to move Southwest Barrows Road to the other side of a creek and to get financing, the project has taken nearly a decade to pull off. Cain jokes that the process dragged on for so many years that “we almost had to change the name. Progress Ridge wasn’t really working any more.”

Now that he has received a $45 million loan from U.S. Bank and has the area 75% leased, Cain is visibly relieved. He points out amenity after amenity as he works his way from the pond with the floating dock to the picnic area outside of New Seasons and up the stairs to the living room theaters of Cinematopia, which will contain in-theater bathrooms with their own screens, enabling moviegoers to use the facilities without missing a line of dialogue.

“The more we do these things, the more we want to make places where people want to be,” Cain says. “You spend 10 years building a project, you’re not just blowing and going. You want to build something that will last.”

Progress Ridge is likely to be a hit with the people who have bought homes in the dense surrounding neighborhoods. It will also pull a certain amount of traffic away from the older strips that are suffering, potentially adding new pieces to the museum of failure. As with other examples of the latest trends, it does little to solve the puzzle of what to do with the areas that have missed the trends. But Cain predicts even the most challenging areas will transform over time. He has met with the planners trying to revitalize McLoughlin and he says he sees potential there, calling it “the most undervalued stretch of property in the region.” He can envision a completely different strip there. “You need people living there and you need cool things to make them want to be there. Give it 15 years.”

The committee trying to rebuild McLoughlin is hoping to get things going sooner than that. They have hired a team led by Portland planning guru John Fregonese to turn their vision of an improved strip into a realistic plan. The team is studying traffic patterns, rental costs, local demographics and economics, as well as models of strip redevelopment from around the nation. They will be meeting with community members on May 21 and plan to release a report by September.

Fregonese says the strip on McLoughlin has more going for it than meets the eye, with a surrounding population equivalent to the City of Corvallis and a median household income of $62,000. “It’s the kind of environment where you can’t change around the whole corridor. You have to start with nodes, start someplace and be successful and then move onto the next thing. Because the corridor is too big to fix all at once, and it could really use a center.”

Fregonese says the strip on McLoughlin has more going for it than meets the eye, with a surrounding population equivalent to the City of Corvallis and a median household income of $62,000. “It’s the kind of environment where you can’t change around the whole corridor. You have to start with nodes, start someplace and be successful and then move onto the next thing. Because the corridor is too big to fix all at once, and it could really use a center.”

The prospect of a new light rail line through the area “gives you an opportunity to do some things you wouldn’t be able to do otherwise,” Fregonese says.

Abe Farkas, development services director for the economic consulting firm ECONorthwest, says the preliminary research indicates that McLoughlin could be a good location for retailers selling building materials, clothing and accessories, and some food services. Farkas is also looking into a strategy of developing rental housing, to lure young newcomers to the area and help change its image.

A mixed-use apartment on the McLoughlin strip would be a tough sell at this point. The area is so auto-oriented that walking can be unpleasant and potentially dangerous. Everything about the area is geared toward catching the attention of passing motorists. Convincing people to move in and spend some time will require changes in image, design and ambience.

Still, the mere fact that some of the region’s top planners are exploring ways to rebuild a place like McLoughlin Boulevard indicates that the trends identified by the Urban Land Institute are serious. The commercial strip as we know it may eventually become a thing of the past. Something else will evolve to replace it, and whatever it is, it almost certainly will be an improvement.