Sauvie Island businesses hunkered down to survive years of bridge restrictions that hammered their economy. What choice did they have?

THE WAIT

THE WAIT

Sauvie Island businesses hunkered down to survive years of bridge restrictions that hammered their economy. What choice did they have?

By Abraham Hyatt

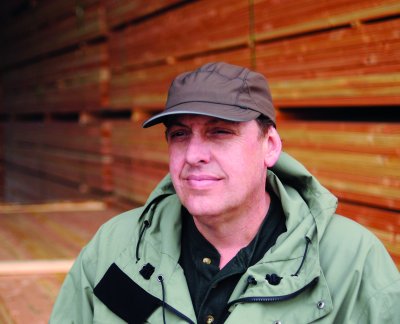

From the cab of a front-end loader he’s driving through the Alder Creek Lumber yard, Dave Koennecke would be able to see the upper arches of the new Sauvie Island bridge if he were to look up. Instead, he’s maneuvering the loader toward a log truck towing two trailers: one empty, one full of logs. Koennecke lifts the logs with the loader’s giant pincers and drives away.

A few minutes later, he’s in his truck driving across the yard to the mill offices. “Do you see that?” he asks as he jumps from the cab. He’s pointing to the now-empty log truck that’s pulling up to a set of scales. “Only one half of a load. That’s what every truck is like.”

Koennecke is an energetic man in his 50s with a bald pate and a ring of dark hair around the sides and back of his head. He’s wearing a dark outdoor-wear vest, jeans and boots. In the 1960s his father built the mill in its current location on the southern tip of Sauvie Island (the company’s roots go back to the Hood River area in the 1920s). Koennecke is a shareholder in the company and its vice president.

|

He’s also chairman of the Bridge Committee, president of the Sauvie Island Boosters Association and has a binder in his office several inches thick of documents on the island’s 58-year-old bridge. He has testified in Salem about economic hardships to island business due to trucking weight restrictions on the decrepit bridge, held countless meetings with elected officials and helped organize the island’s residents to push Salem and Washington, D.C., for funding for a new span.

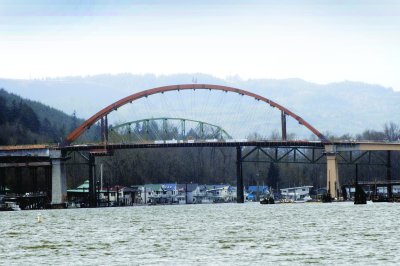

The old Sauvie Island bridge is a sliver of metal and concrete that stretches across the Multnomah Channel and connects the island to the world. It’s a decaying link — a bridge that can’t bear the weight of a fully loaded semi truck. But what the bridge cannot bear, the island’s farms, ranches, nurseries and lumber mill must. They’ve lost uncountable dollars in revenue since December 2001 when the weight restrictions were put in place. Somehow they’ve survived. And now their burden is about to be lifted.

Next to the old bridge, a new $40 million bridge has been growing over the past two years. It’s wider than the old bridge. It’s taller. It’s easier to drive onto and off of. It’s almost done — as early as June, perhaps. Until then, the old bridge shudders and vibrates as each semi creeps over it. The island’s businesses wait and lose a little more money as each day passes — like they have for the last seven years, five months, and what feels to some like countless days.

|

KOENNECKE DRIVES HIS TRUCK over the gravel road that links the mill to the island’s main road as he describes the history of the old bridge: It was installed in 1950; up to that point a ferry was the only way across the channel. In 1998, the Oregon Department of Transportation found that it met “minimum tolerable limits to be left in place as is.” In December 2001 an inspection crew found structural faults on the island end of the bridge. The original weight limit on the bridge was 105,000 pounds, the weight of a standard commercial load. That December, the county radically lowered the limit to 40,000 pounds. To put that in perspective, Koennecke says, the weight of a typical empty logging truck is 30,000 pounds.

Any island business that relied on trucking faced a hard road: the island’s farms and nurseries, which need truckloads of lime and fertilizer; the ranches, which need truckloads of feed; and the mill, which needs truckloads of logs. Then, several months later, the county was able to hold the bridge’s cracking girders together with steel bandages.

Koennecke pulls into a gravel parking lot at the base of the new bridge on the mainland side. He honks a hello to the project manager who’s climbing up stairs to the deck of the bridge. The underside is a mass of pilings and scaffolding. Koennecke talks about them as if he knows each pillar personally.

As he drives back across the old bridge the tires on his truck make a thump-thump noise as they hit steel plates set into the road. These are the bridge’s metal bandages, life support for the bridge. They’re also meager life support for the island’s largest businesses: JD Ranch, Bailey Nurseries, Columbia Farms, Hall Ranch, Delta Farms, Alder Creek Lumber. After the bandages were installed, the weight limit was increased to 80,000 pounds — which has been just enough to get by on.

That doesn’t mean it was easy: Some farmers, like Bob Egger at Delta Farms, stopped growing certain crops — sweet corn and green beans in Egger’s case — that could only be shipped in mass quantities.

Alder Creek Lumber didn’t have the option of stopping shipments. But a typical fully loaded log truck weighs about 88,000 pounds. The company pays the same as they would for a full load, but loses the cost of one load every eight trips. Multiply that by seven years.

It’s not just lost loads. Trucks with double trailers have to park off Highway 30, unhook one trailer, drive onto the island to unload, then come back, pick up the other trailer and head back to island. Koennecke pays trucking companies an additional $25 a load to compensate for the inconvenience.

The island businesses have lost collectively millions of dollars transporting goods in reduced truckloads — every load taking them to the wrong end of economies of scale.

Seven years is a long time for a business to bear that heavy of an economic burden. No farm or ranch closed down because of the bridge. If you ask why, the answer people give is deceptively simple: Because we knew a new bridge was going to be here someday.

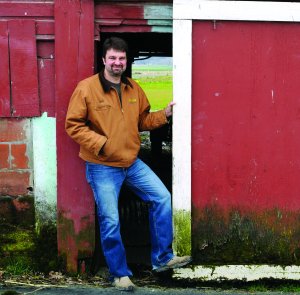

THE ISLAND’S RESIDENTS didn’t just sit and wait for that day, however. Three miles up the road from Alder Creek Lumber is perhaps the most recognizable farm on the island: The Pumpkin Patch. Bob and Kari Egger own and run both the Pumpkin Patch and Delta Farms. On a mid-March afternoon, Bob is standing in the iconic red Pumpkin Patch barn. This is where, come late summer, everything from cabbage to strawberries will be for sale. Today it’s cold and empty, with farm equipment parked where weekend shoppers from Portland usually wander.

|

Egger leans against a checkout stand and describes how he stood in front of county commissions in a meeting after the weight limit was lowered. The island is zoned for agriculture, he told them, but if farmers are physically unable to farm, they have the legal right to develop their property. Egger actually likes the current zoning; he hopes to pass his farm to his son. But if farmers couldn’t grow crops on their land, what choice did they have but to develop the property?

Maria Rojo de Steffey had just stepped into her job as county commissioner for District 1, of which Sauvie Island is a part, when the first weight reduction happened. Islanders felt they’d been neglected, she says, and there was a lot of anger and frustration. But unlike other bridge replacement efforts, like Sellwood in Portland for example, the businesses and residents of Sauvie Island formed a tightly knit coalition, she says. And that became a powerful tool.

“It let me really pound on the economic importance of the island to the rest of the community,” she says. “People got it. That’s what made the difference.”

There’s a physical example of that unity. It’s a one-inch thick, bound volume of letters asking for help that dozens of businesses on and off the island sent to U.S. senators Gordon Smith and Ron Wyden less than two months after December 2001. There are letters from farmers, from nursery owners and their employees, from dairy and bed and breakfast and sawmill owners. There are letters from 14 timber-related companies from around the state explaining how Alder Creek was crucial to their business. Weyerhaeuser wrote a letter about the importance of a new bridge.

|

There are pictures with scrawled messages from schoolchildren: “Please help us pay for a new bridge. The old bridge has a crack in it.” “Please give us money for the bridge or else the bridge will fall.”

THEY GOT THE MONEY. In a county with an expected $195 million shortfall in transportation money over the next 20 years, Sauvie Islanders walked away with more than $38 million in federal funding in 2003. The new bridge broke ground in January 2006. Next month, if all goes well, there’ll be a grand opening party.

But what if the county had decided it didn’t have the resources to fix the bridge? What if a new bridge had turned into the same tug-of-war that’s engulfed the Sellwood Bridge replacement efforts? Or the I-5 bridge over the Columbia River?

Koennecke is leaving the bridge, driving back to the mill, when he’s asked that question. He shakes his head as if that option simply wasn’t possible. As he drives beneath the old bridge, he stops his truck in the middle of the road and looks up through the windshield at the underside of the steel-plate bandages.

He points out a visible crack in the concrete. “We’re landlocked. How would we have farmed? They knew they were in a situation where they had to make it work,” he says. “The county knew they owed us a bridge.” Then he drives under the old and new bridges and back to the mill.

Whether it was ever articulated by the islanders, the county or an elected official, creating a new bridge was about more than a concrete-and-metal span across the Multnomah Channel. The steel bandages on the dying structure didn’t just keep businesses alive, they also allowed Sauvie Island to stay truly connected to Multnomah County. Because a bridge for only cars is only half a bridge. Without the band-aids, it would have been a bridge for the birdwatchers, the beachgoers, the Sunday drivers from Portland.

But it’s the businesses that make the largest agricultural area in the state’s most populated county what it is. It’s the third-generation farms, hundreds of workers at dozens of businesses, and the farmland and pastures that make Sauvie Island what it is.

To keep it that way took patience and the ability of islanders to shoulder a heavy economic burden. It took time. It took the belief that someday — a crucial and imperative someday — the waiting would end.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]

Bob Egger, owner of the Pumpkin Patch and Delta Farms, looks forward to the new bridge opening: “It’ll make business a lot more affordable.”

Bob Egger, owner of the Pumpkin Patch and Delta Farms, looks forward to the new bridge opening: “It’ll make business a lot more affordable.”