Large sawmills are high-tech workplaces.

The mill that contained the twin-blade saw is silent. Craig Kircher, the head rig sawyer at a Hampton Lumber-owned sawmill in Willamina, says “I can run it for you.” He reaches over to press one of the dozens of buttons on his console and the whole building springs to life. The whirring sounds of the conveyor belts transporting the logs are quickly drowned out by the deafening buzz of the saw blades.

From his perch above the mill floor, Kircher is able to command the entire process. He monitors the lumber’s progress on video screens. Sections of logs enter one side of the building and rough boards come out the other. But there is a lot more to the process that turns a tree into a finished product.

Founded in 1942 in Willamina, this was Hampton Lumber’s first sawmill. It now has facilities throughout the states of Oregon and Washington. Mill Manager Brad Blackwell gave me a tour of the smaller and more modern of the two mills on the property.

Hampton buys expensive, high-quality logs and uses them as efficiently as possible to produce premium lumber.

Producing 380 million board feet a year takes a lot of logs. As much as 15 rail cars worth of timber is delivered every day to a lot adjacent to the mill. Much of the wood comes from Hampton-owned forests in the nearby coastal mountains. From there the logs are moved, one truck-load at a time, across Willamina Creek to the sawmill.

The logs are then fed through a bark remover. From there they are sent to the bucksaw, the first of many blades faced by the “stems” on their way to becoming boards.

Most of the logs are delivered at length of 40 feet. The bucksaw cuts them into shorter chunks for easier handling.

The process is so automated that Bucksaw Operator Mike Ulery says, “I’m just a glorified babysitter.”

The mill we toured was called “The Twin” because it uses two blades allowing it to make two cuts simultaneously. The Larger “Quad” mill is able to make four and can handle logs of larger girth.

At the helm of “The Twin” is Kircher. With Kircher at the controls the mill can saw between 10 and 15 logs a minute.

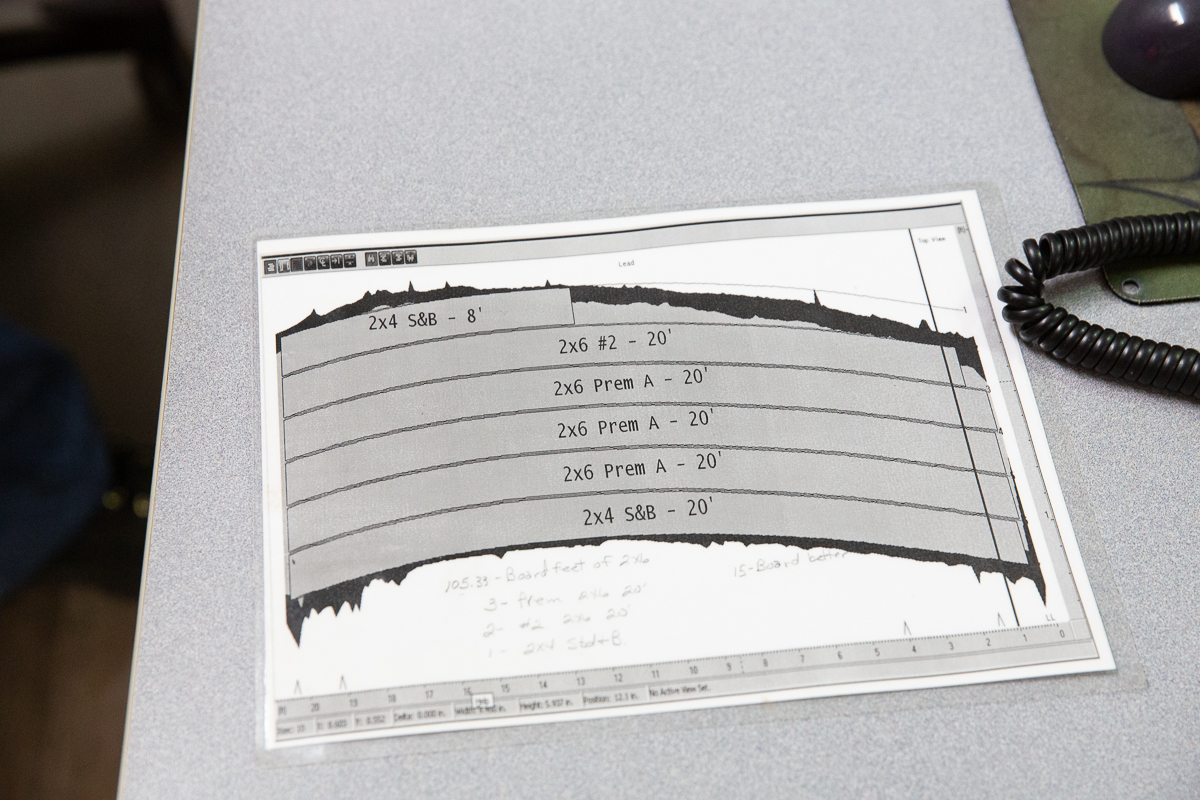

Every log is scanned and mapped to calculate how to turn it into the most board-feet of lumber possible.

Curved logs are mapped to create the highest yield they can produce. The boards will flatten out once they are cut.

Once the rough boards have their edges trimmed they are sent over to the planer machine which will smooth them and make their thickness uniform. The planer is located in an adjacent building.

Both the twin saw mill and the planer (pictured above) are housed in buildings as large as small airplane hangers.

High-speed conveyor belts shoot boards into the planer at a rate so high the wood looks like a blur.

Mill Manager Brad Blackwell explains how the planing blade smooths the surfaces of the lumber. The blades on the wheel need to be changed every couple of days. While in operation the planer makes a painfully loud sound. Hearing protection is required throughout the mill.

One of the automated features that saves the most time and manpower is the GradeScan. This machine scans each board with a bright light to gauge the quality of the lumber. When wood grading was done manually it would take 16 people to do what three can accomplish now with the technological assistance.

Because the GradScan can’t see everything, a human grader still serves as backup and will mark boards that have been incorrectly evaluated by the machine. As the boards move through on a conveyor belt, their grade is projected onto them in yellow green light from up above.

Once the boards are smooth and graded a binding machine wraps them together.

Thirty percent of the wood is then placed into large kilns to be dried for between 40 and 50 hours at temperatures so high it takes the lumber three days to cool. The rest of the boards are sold “green,” meaning that they haven’t been dried and still possess their natural moisture content.

Hampton sells boards to Home Depot and other retail outlets. The company only buys the highest quality logs and they it pays a premium to do so. Blackwell says “We pay a lot for a log so we try and get as much value out of it as we can to maximize our recovery.”

Automation requires a lot of capital investment, but this will likely become the norm at larger sawmills across the country. The low margin on lumber means that Hampton has to be selective about its raw materials and efficient in how they it runs production — the kind of efficiency best suited to machines.

This piece is a companion story to another mill profiled a few weeks ago. Western Cascade Industries uses a more labor-intensive approach to get value out of low-quality timber.