As design becomes an essential part of business strategy, a Portland icon flips the script — and makes business an essential part of its design strategy.

Exitus wanted a case.

The Portland-based startup, makers of a wearable system used to improve communication during a crisis, had everything they needed to launch their business: powerful software, an expert executive team made up of former Navy SEALS and customers hungry for a solution.

Most importantly, they had financial backing, a baked-in vetting of the company and product. What Exitus lacked was an actual, physical enclosure for their product.

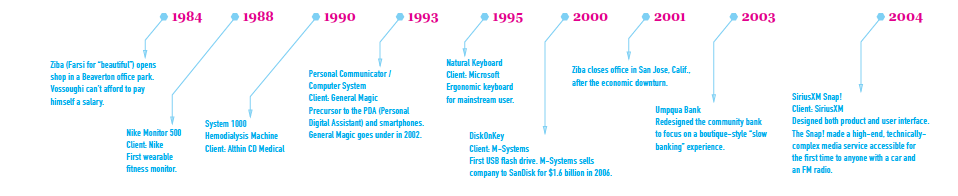

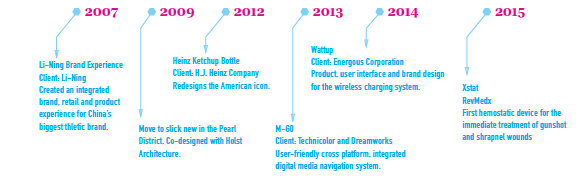

So they approached Ziba Design. It made sense. Over the last three decades, Portland-based Ziba has grown into one of the world’s preeminent industrial design consultancies, creating keyboards for Microsoft and ketchup bottles for Heinz.

The 120-person firm, with a satellite office in Tokyo, has also moved beyond product, designing experiences, graphics and software interactions — diving deep into businesses, facilitating innovation by identifying trends, sharpening brands and creating new values for clients like Umpqua Bank, REI and Reebok.

Still, Exitus didn’t want any of that; Exitus wanted a case.

Or so they thought. After a one-day “ideation” workshop held in Ziba’s Pearl District office building, Exitus got a case and a new partner: Ziba Labs. An arm of Ziba, Ziba Labs is incubating Exitus, offering consumer insights, business savvy, and yes, co-investment to the startup with a goal of going from initial concept to market launch in nine months.

Like many large design firms, Ziba proper walked a similar path before, accepting startup work for the promise of future payment, with limited success. As a separate entity, 5-year-old Ziba Labs shoulders that burden by design; taking on cash-strapped startups or incubating their own ideas while buffering Ziba from financial risk. It’s a strategy the firm hopes offers the best of both worlds — at a time when the design business and the business of design are changing at a rapid pace.

It’s a big task, but one that Ziba is comfortable delivering. They’ve certainly done it before. “We have a track record of execution,” says company founder Sohrab Vossoughi.

Energetic and passionate, Vossoughi doesn’t just walk into a room as much as bound in. Loud but not bombastic, the Iranian-born designer gestures as he talks, clearly excited about the future of Ziba and Ziba Labs at a pivotal time for the industry. He started the first company 32 years ago, after a six-year stint with Hewlett-Packard, growing it into one of the world’s most respected design consultancies. Clients they can name (the industry is secretive by nature) include Procter & Gamble, FedEx and Daimler.

Ziba’s output can be found everywhere. Products they’ve designed are in your home, on your street, on your computer screens and in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection. They’ve enjoyed success in a volatile industry, witnessing design’s rise above gee-whiz products, pretty packages and eye-catching graphics to become an essential part of business strategy.

How did design win a seat at the big table? In 2016 — when products come to market faster and faster, competition attacks from all angles and technology allows anyone with an idea to build a business in days — design has become synonymous with innovation, another industry buzzword. Big companies have doubled down on design’s promise to give them an edge — in product development, in branding and on ubiquitous social media channels.

Witness: Johnson & Johnson, PepsiCo and Philips Electronics NV have added chief design officers to their C-suite. GE and IBM are expanding their in-house design teams at a dizzying pace. Capital One, Google and Facebook choose acquisition, swallowing up design firms whole, to beef up their design presence. Even design consultancy giant Lunar was not immune. It was bought by management consultancy giant McKinsey & Company in 2015.

Through it all, Ziba, with Vossoughi at the helm, has remained independent and proudly cash positive. (The company declined to reveal more financial information.) Now he’s left to head Ziba Labs. What started as an internal skunkworks project has grown into an independent venture financially walled off from Ziba. Staff, however, move freely between the two. The process has energized Vossoughi.

“It’s crazy to launch a startup now,” says the 59-year-old with a twinkle in his eye. “But my doctor said it’s okay, this kind of pressure is good. It keeps me alive.” Project ideas can come from within — like the JumpSeat, an auditorium-seating solution installed in their space and now licensed for purchase — or from outside, like Exitus.

The benefits to Exitus are immediately apparent. “Ziba has increased our chance of rolling out correctly and sustainably,” states the company’s CEO, Anthony Levrets. A former college basketball coach (not one of the ex-Navy SEALS but an intense, enthusiastic leader nonetheless), Levrets explains, “They’ve cleaned up our messes,” pointing to Ziba’s help with everything from resources to brand development to advice on how to pitch investors.

“We came to an industrial designer for a case and now [Ziba’s] CEO is helping us with financial projections.”

Ziba CEO Christof Mees, 49, is driven by more than altruism. “For us this is a unique opportunity to participate in a highly accelerated business that can become very large,” he says, noting Exitus’ smart network of connected people is a manifestation of the Internet of Things. “Let your imagination run free on where you can apply that.”

Christof Mees has sat on Ziba’s board since 2011. Named CEO in 2015, German-born Mees’s calm, measured yet approachable demeanor plays well off of Vossoughi’s enthusiasm. The two clearly enjoy each other’s company, talking over each other one minute, riffing off the other’s thoughts the next.

Specializing in innovation strategy and innovation operations, Mees has over 16 years of management consulting experience under his belt. He comes to Ziba at a serendipitous time. Just when business is nurturing design by hiring CDOs and building in-house teams, Mees is a businessperson — with a Ph.D. in macroeconomics, no less — leading a design firm. It’s unusual; most design firms are run by designers.

It may be enough to give Ziba its own much-needed edge. “Our clients are looking for something that helps them drive business value and get consumers to open their wallets,” Mees explains. “They pay us with hard dollars and we give them hard dollars back.”

How does a design firm drive business value? “We need to move out of the ‘I can do beautiful things’ to ‘I can help you make an impact by getting something better out to the market faster,’” Mees says. In sum: Ziba, which has traditionally supplied the “what” (as in what companies should be making, creating or offering), is betting hard on Mees to supply the “why.”

As Ziba Labs moves forward, Mees says most of Ziba’s income will continue to come from traditional consultancy work for long-term clients like Procter & Gamble, Clorox and FedEx.

The firm will continue to serve the medical-device market as well. Ziba has found success in this arena with products like the SAM Junctional Tourniquet from SAM Medical and XSTAT from Wilsonville-based RevMedx, Inc. The SAM Junctional Tourniquet, a battlefield device used on groin or armpit wounds, was fielded by the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Agency this year, while XSTAT, a syringe-like applicator that delivers small sponges to a wound, was just cleared by the FDA for civilian use.

Ziba is also working with smaller, hometown favorite New Seasons Market. The Portland-based grocer is gearing up for a large expansion, six new stores a year, up and down the West Coast with — perhaps — an eye toward a national presence. (Again, Ziba is tightlipped about the true scope of their work. During interviews, a PR person was close at hand, referring to a thick stack of paper in her lap about what designers could and couldn’t say.)

The work Ziba did for the grocery chain — creating messaging standards for the store and designing the packaging and labels for the in-house brand — looks pretty simple and straightforward. It wasn’t. “Ziba was able to provide the strategic resources, creativity and the strong discipline needed to help New Seasons distill and define our brand essence and platform,” says Dina Keenan, New Seasons’ chief marketing officer via email.

That distillation and definition process required a dizzying variety of disciplines: creative director, consumer insights specialists, trend specialists, digital designers, environmental designers, product designers, service designers and brand strategists. “We will understand [their] DNA,” says brand insights director Mattias Segerholt.

This isn’t your mother’s design firm.

Ziba houses a dizzying array of disciplines under one roof.

As executive managing director Chelsea Vandiver observes: “We have more job titles than people.”

To wit, Ziba job categories include:

Ethnographers

Brand strategists

Story tellers

Communications designers

Environmental designers

Product designers

Service designers

The goal, of course, is to hedge New Seasons’, and majority stakeholder Endeavour Capital’s, bet. Rolling out a grocery store costs $10 million, according to Segerholt. Getting it wrong is not an option.

“New Seasons has big aspirations, but it’s a challenge to grow and still be that cute little shop down on the corner,” says Tom Gillpatrick, executive director, of the Center for Retail Leadership in the School of Business Administration at Portland State University. “Engaging Ziba is a smart move.”

It’s a smart move for Ziba, as well. While the firm continues to help other companies drive innovation, they are simultaneously repositioning themselves in the marketplace. The new business focus is one example. Here are a few others.

As a design firm Ziba is admittedly an anomaly. Take their Pearl District headquarters, for example: At 42,000 square feet, it’s enormous. Huge volumes of air and light fill the perimeter of the space and lobby, while project rooms (where the secret sauce is made) are visually private.

There’s no foosball table, no spray-painted walls, no dogs running around; conference rooms are numbered, not saddled with cutesy names. It’s “boring” in Mees’s words. Yet every fixture, finish and stick of furniture has been designed with a single purpose: facilitating the design process.

The building’s aesthetic — cool concrete floors, warm woods, whiteboard walls — mirrors its Portland address. “It’s part of the community culture,” says Mees. For contrast he points to competing firm IDEO, headquartered in flashier Palo Alto. “IDEO is much more aspirational in its message. They say, ‘We know how to change the world.’ Oregon is humbler.”

Portland may be more grounded, but the location has its challenges. The region is rich with creatives, between 4,000 and 5,000 in Mees’s estimate, spread between big- name firms — Nike, Wieden + Kennedy and Adidas — and small firms as well. But increased demand and rising costs of living translates into rising headcount cost for Ziba.

The company is working on different engagement models to attract millennial talent who want a temporary gig instead of a full-time job. They also sift through an enormous pool of potential hires, around 1,500 a year, to find the 10 or so they take on annually. The total headcount remains relatively stable over the years despite dynamic economic cycles.

Designers they do hire have to be highly adaptable to fit into the changing nature of Ziba’s output. “It’s not for the faint of heart,” says Chelsea Vandiver, 42, executive managing director of creative. Direct, no-nonsense and to-the-point, she explains:

Designers they do hire have to be highly adaptable to fit into the changing nature of Ziba’s output. “It’s not for the faint of heart,” says Chelsea Vandiver, 42, executive managing director of creative. Direct, no-nonsense and to-the-point, she explains:

“Three years ago 70% of our work was industrial design. Today 70% is interaction design [anything you see on a screen], but we didn’t change staff.”

Examples of their interactive design work include an app for Technicolor and DreamWorks that allows users to access all of their media on one screen, and a display for Adidas that incorporates interactive videos and graphics with a physical display.

Mees’s plans for Ziba are not radical: Carefully grow their top and bottom lines while remaining cash positive. They will continue to rely on their portfolio of long-term clients to provide most of their revenue while hoping the high-risk projects, walled off at Ziba Labs, will seed their pipeline.

While Vossoughi will freely admit he’s “not good at running companies,” his proven track record of execution lends confidence to investors. Their first major startup, parking app Citifyd [02] raised funds quickly — $1.4 million to date — telegraphing the Labs’ potential success.

“People think we did magic to raise money locally for Citifyd, but this is where the value of my 32 years comes in,” says Sohrab Vossoughi. His reputation garnered enough trust to secure the funding to get the parking app startup off the ground. The app works like Airbnb for parking spaces. People, or companies, put spaces up for drivers to rent by the hour. The Portland Timbers tested the app successfully last year. The Trail Blazers and Moda Center are on board and two more cities with sports franchises are coming on as well. Venues are looking to make parking convenient to enhance the overall fan experience.

It may be enough to keep Ziba viable and independent in an industry riven by volatility and consolidation. Certainly there’s business value in focusing Vossoughi’s attention on the project.

“Sohrab is most passionate when he’s creating something new,” says Mees. In five years, the Labs have already grown from a place for Zibites to execute passion projects to an incubator for outside ideas — as long as those ideas come with their own funding. Mees can envision a future where Ziba Labs raises its own funds, but the financial wall between Ziba Design and Ziba Labs will remain constant.

“Capitalism has many good things about it, and one of them is if you have a great idea, you’ll get money,” explains Mees. “If you can’t convince someone whose business is investing money, why do you think I know better?”

It’s as if the design firm has taken itself on as a client, creating a new business model that allows it to stay relevant — and independent — while reducing risk all around. After 30-plus years in the industry, it’s a smart bet. Ziba has a history of pivoting, evolving from an industrial-design firm to a consultancy that offers the full design stack all while staying in tune with the zeitgeist.

And now that the profession has moved into the C-suite they’ve invited the C-suite in. If it weren’t so cliché, one could imagine Vossoughi saying, with a wink: To stay viable, design must always go back to the drawing board.

A version of this article appears in the September issue of Oregon Business