Oregon is creating a marketplace where small businesses can buy health insurance. But will this exchange improve quality and make health plans more affordable?

Oregon is creating a marketplace where small businesses can buy health insurance. But will this exchange improve quality and make health plans more affordable?

By Linda Baker

|

“We want to design an exchange that is so good people are going to want to be part of it as opposed to being pushed into it,” says Aelea Christofferson, a Bend businesswoman who serves on the Oregon Health Insurance Exchange Board.// Photo by Randy Johnson |

Lurking behind every Oregon small business is a health insurance tale of hardship and woe. At Hawthorne Auto Clinic in Portland, co-owner Jim Houser pays $100,000 annually in premiums to cover his nine full-time employees and their families. That’s about double the amount he paid 10 years ago and 20% of payroll, he says. Aelea Christofferson, owner of ATL Communications in Bend, is locked into a one-size-fits-all plan that compels her older employees to pay the same deductible as her employees with small children. Jose Gonzalez, principal of Tu Casa Real Estate in Salem, has no insurance for himself or the eight agents he employs. “It’s too expensive,” he says simply.

Never-ending rate increases and lack of options are among the reasons why Christofferson, Houser and Gonzalez have high hopes for a new health-insurance program created by the passage of Senate Bill 99 this past June. Scheduled to launch on Jan. 1, 2014, the Oregon Health Insurance Exchange will be an online marketplace where individuals and employers with fewer than 50 employees can shop for health insurance while potentially qualifying for small-business tax credits and individual subsidies. The goal is to create an easy-to-navigate website where consumers can compare health plans on the basis of cost, quality and individual health needs.

“The exchange will be a trusted resource,” says Gonzalez, who, along with Christofferson, is one of three small-business representatives Gov. John Kitzhaber appointed to the 3-month-old Health Insurance Exchange Board. (Houser is a member of the Health Exchange Consumer Advisory Group.) “It will allow me to protect my family and employees.” Other small-business advocates are even more enthusiastic. “To call the exchange transformational is too little a word,” says Ryan Deckert, president of the Oregon Business Association. “It will change the whole way individuals and businesses purchase health care.”

But if anticipation is running high, the challenges — and uncertainties — ahead are significant. The board, which is crafting a business plan for the exchange, due February 2012, must also resolve a variety of complex policy issues, ranging from types of insurance plans and rates to the construction of a consumer-friendly website. At stake is more than the design of a system that will appeal to small businesses and insurance companies alike. A bigger question is whether the exchange, which is less an overhaul of a broken system than an incremental market-based reform, can actually make a dent in the affordability and accessibility of health care — especially in Oregon, which already has one of the most competitive small-group insurance markets in the country.

“The long-term goal is to leverage the purchasing power of the exchange to help improve health-care quality and outcomes, which will eventually impact cost,” says Rocky King, executive director of the Oregon Health Insurance Exchange, a public corporation. If the exchange fails to accomplish this broader task, says King, its impact will be limited. “It will be nothing more than a market aggregator.”

|

About 17% of GDP goes to health care, says George Brown, CEO of Legacy Health System. “The insurance exchange is one solution on the horizon, but there will be many more.”// Photo by Randy Johnson |

Oregon isn’t the only state restructuring the way individuals and businesses buy health insurance. In 2010, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act, which requires everyone to purchase insurance in 2014 or face a penalty. The federal law also requires states to set up health-insurance exchanges, or have the federal government do it for them. So far, around 12 states have passed legislation creating online marketplaces; Massachusetts and Utah already had such marketplaces in place before passage of the federal law. Forward movement notwithstanding, opposition to national health care reform is one of the challenges facing the exchange initiatives. Along with the National Federation of Independent Business, 26 states have brought a lawsuit against the federal government calling for the Affordable Care Act to be struck down. That case is now awaiting a hearing by the Supreme Court.

In Oregon, the federal government is still on track to pay for all the exchange development costs and the first year of operation. Although many details have yet to be hashed out, some of the goals are relatively straightforward: expand health insurance coverage by targeting groups that typically find coverage out of reach, including small businesses and individuals making up to 400% of poverty-level income. Then sweeten the pot by offering more choice and federal subsidies: specifically, a small-business premium tax credit of up to 50% of a business’ share of its employees’ premium, available to employers with an average employee wage below $50,000. Insurers will be required to offer a set of essential benefits, standardized and rated across carriers so people could compare apples-to-apples cost, quality and benefits. Plans will also be offered at four different levels of coverage, with a “platinum” plan covering a higher percentage of a particular benefit — a hospital stay, for example — than a “bronze” plan.

For their part, small employers will no longer be forced to buy a one-size-fits-all plan for their employees, whose insurance needs vary depending on age, health and family status. Instead, employees would likely be given a fixed contribution, so that “people can go online and choose insurance that’s best for them,” Christofferson says, using a common descriptor. “It will be the Travelocity of health care,” she says.

George Brown, CEO of Legacy Health System and an exchange board member, puts the program in broader perspective. The online marketplace will bring together like-minded small employers, giving them the purchasing clout — and larger risk pool — of a Nike or Intel. “The exchange allows parties to come together to barter their way toward what’s going to be bought and what’s going to be sold, with the oversight of state government to make sure standards are going to be met,” says Brown.

It’s an ambitious vision. More than a web portal, the exchange, so proponents claim, will be a market driver that leverages the power of hundreds of thousands of freshly insured individuals and employees of small businesses. But there’s a catch — or several of them. Far from being a single-payer system, the new marketplace depends on the participation of willing sellers — insurance carriers — as much as buyers. And two years before the exchange opens for business, these interests are not always aligned.

For example, even as small-business owners tout the opportunity for employees to choose different carriers, insurers raise the specter of “adverse selection” scenarios such as one carrier getting only “very old people, or only young people,” says Sujata Sanghvi, COO and executive VP for PacificSource Health Plans. To mitigate that problem, the exchange law allows for several “risk adjustment” mechanisms, in which carriers serving healthier populations help subsidize carriers serving the less healthy.

Nevertheless, says Tom Holt, director of legislative and regulatory affairs at Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon, big questions remain about “how to assess the risk and therefore how to price the products.”

Holt and other insurance representatives tick off a list of other concerns: the diminished role of insurance brokers in an online marketplace, developing the information technology to administer premiums for different employees, and the challenge of attracting consumers to the exchange given the relatively benign penalty — about $600 — of not complying with the federal insurance mandate.

|

“I’m hoping to be one of the exchange’s first customers,” says Jose Gonzalez, a Salem realtor and member of the Exchange Board. But, he says, keeping health-care costs down is also a matter of “personal responsibility.”// Photo by Randy Johnson |

Small-business and consumer advocates raise their own concerns about affordability and accessibility. Outreach to rural and minority communities will be a challenge, says Gonzalez. He would also like to see the small-business tax credit expand to businesses with employees making up to $75,000. “We hope no business is priced out because they want to attract good employees,” he says.

Back to the million-dollar question. Will the exchange help control or drive down the cost of health insurance? That has yet to happen in Massachusetts or in Utah, where small-business insurance inside the exchange is actually more expensive than outside. As for Oregon — in October, the consumer advocacy group OSPIRG released a nationwide study of exchange initiatives, ranking the Oregon law a B minus. One weak point, says Laura Etherton, OSPIRG’s health policy advocate, is “the legislative language failed to direct the exchange to lower costs.”

The exchange will eventually have an impact on cost, just not directly, King and others respond. That’s in part because because federal law requires identical plans sold inside and outside the exchange to have identical premiums. Also, as King points out, the Oregon Insurance Division must approve all health-insurance rates and increases. As a result, Oregon already boasts “the most robust rate approval process in the nation,” according to King. What’s more, Oregon isn’t Kansas, which is one of several states that has only one small-business carrier. About seven carriers serve Oregon’s small group market.

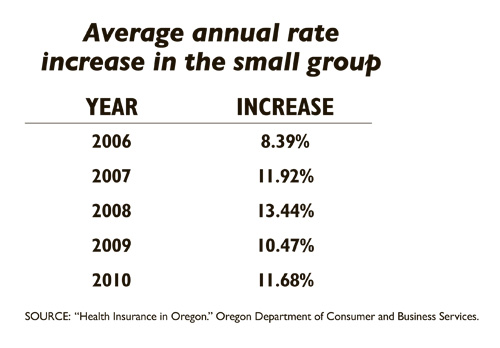

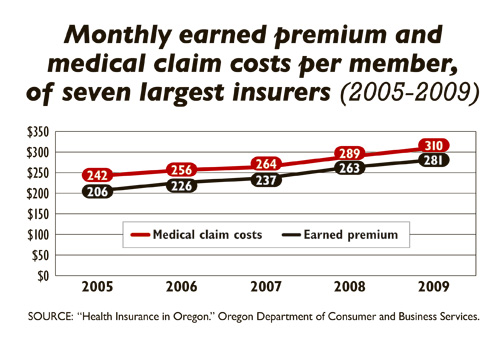

In short, since Oregon is already home to a competitive yet heavily regulated insurance market, the exchange on its own is unlikely to bring prices down. Why isn’t that a deal killer? Contrary to popular opinion, says King, the reason insurance rates are increasing 5%-10% a year isn’t because carriers “are taking the money and pocketing it.” Instead, he says, “service delivery reforms” are the key to controlling health-care expenses.

Unlike Massachusetts and Utah, Oregon’s exchange is not unfolding “in a vacuum… but is part of a whole chain of things happening to address quality and cost,” says Christofferson. One is the development of a new health-care model called the Coordinated Care Organization, which will integrate physical mental and dental services for more than 600,000 Oregonians under the Oregon Health Plan. Subject to approval by the Legislature, the first CCO would launch next July, with a projected savings of $239 million next biennium. Then there is the “health-engagement model,” a pilot available through the Public Employees Benefit Board, linking health coverage to behavioral changes by the participant.

As these and other new initiatives get established, King says, the goal is to fold them into the exchange, where application on a larger scale will further reduce the cost of care. In 2016, the exchange will be open to businesses with 100 employees, and in 2018 to firms with more than 100 employees.

But first things first. “Coming out of the box, with zero enrolled, we can’t negotiate,” King says. “Once I get 300,000 lives in there, we’ll have leverage to move the market.” According to Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at the Health Policy Institute and Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., Oregon is “at the vanguard of the rest of country” precisely because officials are thinking about the exchange “as a mechanism to get delivery system reforms.”

But whether enough businesses and individuals will enroll, whether federal health law will be overturned, and whether the exchange will languish as little more than a web portal, are the uncertainties clouding the future. In that regard, Chris Ellertson, president of Health Net Health Plan of Oregon Inc., speaks for both insurance carriers and purchasers when he says: “We believe there’s going to be some good that comes from the exchange. But there are a lot of question marks, a lot of things that are hard to predict.”

Linda Baker is the managing editor of Oregon Business. She can be reached at [email protected].