Share this article! A little over a year ago, I took a road trip around the Deep South. My kids and I flew into Atlanta, drove to Birmingham, Alabama, and from there retraced the state’s Civil Rights Trail in Selma and Montgomery. It was my first visit to that part of the country, and I was … Read more

A little over a year ago, I took a road trip around the Deep South. My kids and I flew into Atlanta, drove to Birmingham, Alabama, and from there retraced the state’s Civil Rights Trail in Selma and Montgomery.

It was my first visit to that part of the country, and I was surprised — naively so — to find in Birmingham clusters of chic restaurants, craft breweries and coffee bars. If the weather hadn’t been so hot, we would have hopped on the city’s Zyp bike share system.

Long before I first heard the name Doug Jones, I thought of Birmingham as a kind of Portland on the Cahaba.

But Jones is now Senator-elect Jones, and a better, bolder more contemporary comparison is whether Portland should become more like Birmingham.

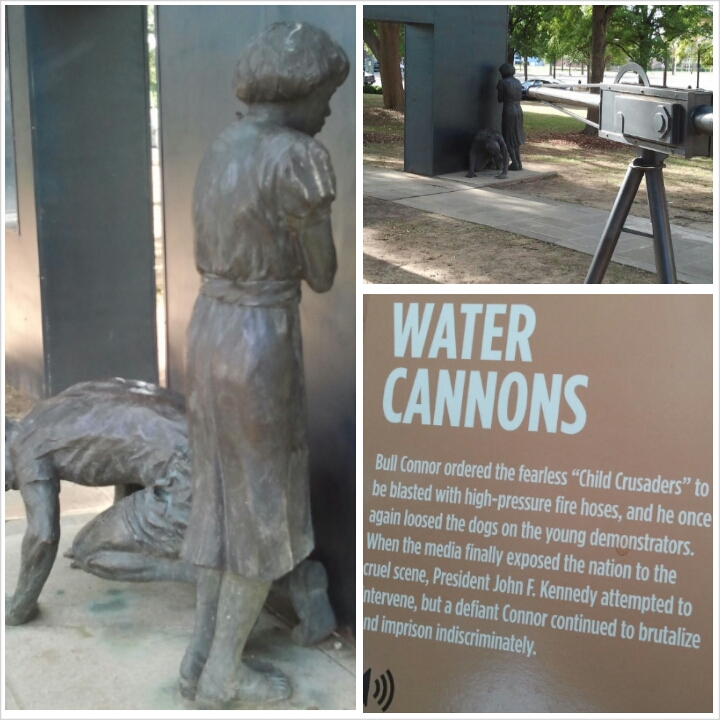

One of the most memorable days of our trip took place in Kelly Ingram Park, located next to the Baptist church where a Ku Klux Klan bomb killed four African-American girls in 1963. (A former federal prosecutor, Doug Jones won convictions of two of the bombers in the late 1990s.)

A memorial to the city’s brutal civil rights battles, Ingram Park features intensely disturbing sculptures of people and events.

Several statues depict snarling dogs and policemen brandishing clubs. Another features fire hoses aimed at civil rights protesters.

This is not a civic space that whitewashes past abuses. On the contrary, the site commemorates the ugliness, fear and violence that defines the fight for racial equality.

The impact is instantaneous, visceral — especially for (white Portlanders) accustomed to patting ourselves on the back for espousing progressive values, even as we continue to bulldoze and displace.

In Montgomery, signs on main streets describing the horrors of the slave trade serve a similar purpose. The plaques put the observer in the shoes of the people who suffered, and in the process nurture a radical empathy that is missing in much of the Portland discussion around race.

White Portlanders feel guilty about racial injustices. Empathy, not so much.

****

On a daily basis I receive pitches from companies touting their diversity initiatives: the hiring of chief diversity officers, the launch of business incubators for minority entrepreneurs.

These institutional and structural changes are important. But they are not enough.

What Portland needs is a literal and metaphorical Kelly Ingram Park, a 21st-century version of Unthank Park, the North Portland space honoring pioneering doctor DeNorval Unthank.

We need to do more than honor the pioneers who broke the color barriers by commemorating our racist past — and making our own Ku Klux Klan history visible and transparent. We need urban designs and corporate culture programs that instill empathy on a daily basis.

The state of Alabama yesterday took another step toward racial healing. Now it’s time for Oregon to catch up to Alabama.