BY JON BELL

BY JON BELL

Developers chase the rental market and change the face of Portland neighborhoods.

BY JON BELL

BY JON BELL

There is a monumental hole in the ground in Portland’s Lloyd District, an area long home to a signature mall, plenty of office buildings and not much more.

The hole is massive, gaping across entire city blocks, a hundred feet deep in some places and of a scale that can be hard to get your head around. Its size shrinks the front-end loaders, dump trucks and excavators that rumble across it, and the hard-hatted workers engulfed look absolutely tiny. The only features that seem somewhat in proportion are three towering yellow cranes rising from the ground and into the sky.

But this chasm will not be here for long. Come this spring, the foundations of a new three-building apartment development should be in place, with upper floors stacking up soon after. By the end of summer 2015, there will be nothing left of the void but a memory. In its place will be an entirely new residential development with close to 660 apartments, ranging from tiny studios to penthouses and nearly 60,000 square feet of retail space. It will be called Hassalo on Eighth and will be just the first of four construction phases that will add thousands of new residents to the Lloyd District and fundamentally redefine a part of the city.

“We think we can create a neighborhood where, right now, it’s just an employment center,” says John Chamberlain, president and CEO of American Assets Trust, the San Diego real estate developer that bought a $92 million portfolio of Lloyd District properties from Ashforth Pacific in 2011. “This is a transformational project for the district and the city.”

Though AAT’s $250 million project is one of the biggest and most influential residential development projects in the city, it is by no means the only one. Developers, both local and out of state, have taken advantage of an ideal mix — economic improvement, an undersupply of apartments and building codes that strongly favor density within the city’s neighborhoods — to ignite an apartment-building frenzy.

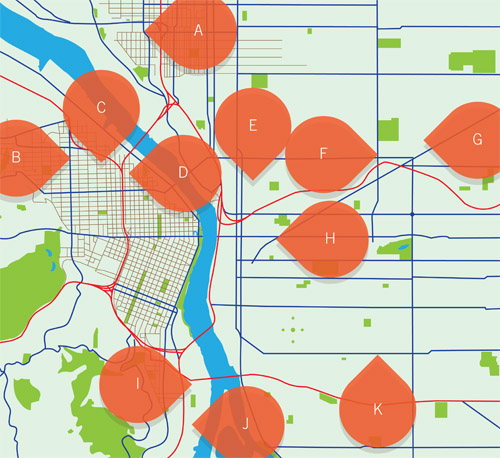

All across the Rose City, new buildings are sprouting like weeds. Here are four stories and 24 units on Southeast Division Street; there are four more stories and 50 more units in the Beaumont-Wilshire neighborhood. Don’t forget the 206 units coming to the North Williams/Vancouver corridor in 15 months at the Cook Street Apartments, the 180 more that will be just across the way in the Aleta or the 211 springing up on Northeast Broadway at 33rd in Grant Park Village.

All these projects merely scratch the surface of what’s been built, what’s under way and what’s on the way. According to a fall 2013 construction report from Mark. D. Barry & Associates, a Portland appraisal company, more than 5,300 units came on the market in late 2012 and 2013, and another 5,000 were under construction and scheduled for completion in late 2013 and 2014.

“They’re definitely building more than they have in the past four years,” says Joseph Chaplik, president of Joseph Bernard Investment Real Estate.

Developers and builders are meeting pent-up demand for rental housing from a growing population and people who are once again finding work and needing places to live. These developers are doing nothing short of transforming some of Portland’s historic neighborhoods, entirely changing the character of some areas or creating brand-new neighborhoods in others.

The apartment boom helps meet the city’s desire for density and development of long-stagnant areas. But it’s also rankling neighbors who bristle at the prospect of increased traffic, parking challenges and the loss of character that attracted residents to these neighborhoods in the first place.

How much longer the market will support such a boom is hard to tell. Estimates of units on the way range from 10,000 to 20,000. Whether it’s two more years or five or eight, the apartment spree will leave Portland neighborhoods much different than they are today: more densely packed with people, woven with restaurants and shops, and central to the city’s ongoing urban evolution.

In 2006 Eric Cress and his business partners, Steven Pontes and Avi Ben-Zaken, decided the Bay Area was no longer where they wanted to focus their business or personal lives. Working essentially as investment managers, the three liked the Portland lifestyle, as well as the potential for infill development in the city’s neighborhoods. So they moved north and founded Urban Development Partners to take advantage of both — and Southeast Division Street was transformed because of it.

The downturn made it tough to invest too widely, and Pontes passed away in 2008 after battling cancer. “It was kind of a nightmare,” Cress says. But when 2009 came around, UDP was ready to move forward. They’d been eyeballing Southeast Division for a couple years, even picking up properties. The street was home to plenty of vacant property in part, Cress says, because it was once slated to be condemned or otherwise folded into the failed Mount Hood Highway project from the 1970s. After that project met its demise, Division was left to linger.

“The street just needed some time,” Cress says.

For UDP, the time came in 2009 with the redevelopment of the Reliable Parts building at 31st and Division into a mixed-use building of apartments over ground-floor retail, including the very popular Sunshine Tavern. UDP and others have since developed more apartment projects along Division that have quickly transformed the street from a sleepy, gritty thoroughfare into one of the liveliest retail districts on the inner Eastside.

Where once a local band jammed in the upstairs of a rental house on Southeast 38th and Division, now a modern four-story building houses residents in 24 units over a Little Big Burger restaurant. City favorites Salt & Straw and Saint Honoré both opened new locations in a mixed-use building on Division last summer. Additional UDP projects are springing up at 3330 and 3360 Southeast Division, and other developers are building at 33rd, 44th and 48th streets, activity that’s snarling traffic and further overhauling the area.

|

| A 30-unit complex on Southeast Division street // Photo by Adam Bacher |

Apartments are helping to completely change other established areas of the city as well. The Prescott, a $29 million, 155-unit apartment building with ground-floor retail, opened in December at North Interstate and Prescott, and the same company — Washington’s Sierra Construction — will build the Cook Street Apartments, a 206-unit development with 15,000 square feet of retail space in the historically African-American North Williams/Vancouver corridor.

That site is the old Hostess bakery property, which for years sat abandoned. New Seasons’ newest store opened in the area recently, and other retail and housing projects are helping the area morph from one of near urban blight to a sought-after, gentrified neighborhood.

The Prescott and its monthly rents of between $850 and $1,900 target hip, urban 25- to 35-year-olds and tech-savvy young professionals who’ve been priced out of the Pearl District, says Brendan Lawrence, development manager for Sierra. “I agree this will sway the direction of the neighborhood going forward.”

E. John, a third-generation, family-owned development company in Vancouver, Wash., is another developer reshaping another Portland neighborhood in the coming years. Long focused on homebuilding and then commercial real estate, the company broadened into the multifamily market three years ago. Since then, the company has built three new projects in Northwest Portland alone, adding 156 units total. The most recent one is an $8 million, 40-unit building called Sawyer’s Row, which sits on Northwest Raleigh at the edge of a sleepy industrial district full of asphalt parking lots and the constant rumble of Interstate 405.

That character will change soon. C.E. John is the master developer for much of the 20 or so acres known as the Con-way property, which is set to become another entirely new neighborhood with a mix of residential, retail and commercial space over the next decade. Though smaller in scale than the Pearl District, the buildout of the entire Con-way property in the coming years will reshape an entire area of the city much the way the revitalization of the Pearl did — by creating a residential community in an area historically fit for industry, warehouses and parking.

C.E. John planned to kick off the $40 million development in January with construction of a New Seasons grocery store out of an old warehouse in what’s to be called the Slabtown Marketplace, and a six-story, 113-unit apartment building called the L.L. Hawkins at Northwest 21st and Raleigh.

“It will be an interesting mix of old and new there,” says Thomas DiChiara, senior vice president of development for C.E. John, “but it’ll really set the stage for the entire district there.”

For parts of the city that have languished over the years, this new wave of construction is truly revitalizing. It’s converting vacant eyesore properties into modern buildings packed with people and the kinds of retail — niche restaurants and bars, for example — that draw not only residents but also folks from across the city and even out of town. Over time, these more desirable areas also help drive up property values.

But not everyone is enthusiastic about the dramatic changes. As new building brings energy into these communities, it also ruffles feathers and triggers side effects that influence the areas’ transformations in ways that not everyone is excited about. Traditional gentrification issues have cropped up in North Portland, as longtime residents, many of them African Americans in traditionally black neighborhoods, find themselves squeezed out by higher housing costs — and other people who can afford to pay them.

While infill projects like those along Division meet the city’s goals for density, their size, lack of parking — something the city didn’t require for such buildings until last year — and overall impact on an area almost always upsets neighbors from the start.

|

| The Freedom Center, a 150-unit complex in Northwest Portland // by Adam Bacher |

Jeff Myhre, president of Myhre Group Architects in Portland, says such issues exemplify the city’s “identity crisis.” “We all want to be this green city based on new urbanist ideals,” he says. “We all want to live in the core and preserve the mountains and the coast so we can go recreate. But the problem is, it requires more density.”

Kathy Lambert has owned Division Hardware and Paint at Southeast 37th and Division since 1987. The neighborhood hardware store is just a block away from UDP’s project at 38th, and it’s across the street from a controversial 81-unit apartment building currently under construction by developer Dennis Sackhoff. Under the city’s prior codes, the building wasn’t required to have any parking for residents.

Lambert is one of many neighborhood residents who has not been happy with all the new development and what it’s bringing to the area. “Just the number of people who are going to be in that building, the garbage, the traffic,” she says. “It’s going to be nearly impossible to get across the street.”

Lambert and other neighbors formed Richmond Neighbors for Responsible Growth to try and limit the size of the building and require parking. While their efforts delayed construction and raised awareness of community concerns, they ultimately were not able to stop the project.

“A lot of people are upset and moving out, but apparently the city doesn’t care,” Lambert says. “It’s like the people in government want it to become like New York City or a large metropolitan area. There are major, major problems with that, and I don’t think it’s right.”

Ben Kaiser has been through his own version of the neighborhood tussle. A former carpenter’s assistant who is now an architect and developer, Kaiser worked with neighbors in North Portland’s Eliot neighborhood to find common ground for a project now called the Aleta. The project will differ from other apartments in that it will be 180 small units of “co-housing” designed for active adults with an eye toward the current trend of aging in place. Area residents felt the 85-foot-tall project was too big and too much for the neighborhood — so much so, in fact, that they took their case to the Oregon Land Use Board of Appeals, which decided in Kaiser’s favor in November. The project will likely break ground this spring and add to the ongoing transformation of North Portland.

“I understand why it’s a point of friction,” says Kaiser, who’s also planning a 68-unit live-work building near Mississippi Avenue this year called Project X. “It was contentious there for a while, but now that we’ve arrived at a solution, I’m hoping we can all put our heads together and come out with a great project.”

It hasn’t been long since another neighborhood-changing building boom plowed through the city. Rewind a few years to before the recession, and recall all the condo construction spreading around the city, from the Pearl District to Northeast Fremont Street to the South Waterfront District. As the market burned brighter, builders overdid the building, the economy tanked and hundreds of brand-new condos sat empty. Many were eventually converted into apartments. Like some of the multifamily projects that are part of the current boom, many of those buildings injected new character into existing neighborhoods by way of expanded retail offerings and housing options for young professionals.

The current apartment market is strong. October numbers from Multifamily NW suggested an apartment vacancy rate of just 3.1% — among the lowest in the nation — and landlords aren’t having much trouble filling units. Rents are on the rise, and concessions like a few months of free rent are a perk of the past.

“We had people sleeping on the sidewalks waiting to sign leases,” says Laura Recko, director of fundraising and public relations for REACH Community Development, an affordable housing nonprofit that opened a $50 million, 209-unit affordable housing apartment building in South Waterfront in 2012.

Even so, it’s not hard to hear the strain in many voices when talk turns to the future and apartment projects not yet out of the ground. DiChiara, from C.E. John, says he’s already heard that some lenders are being more cautious about lending for multifamily projects, and Mark D. Barry & Associates’ latest report notes that at least 12,300 new units on top of what’s already being built have been proposed. Many of those may never come to be, but it is still a hefty number, and the amount of activity currently under way seems eerily similar to the condo craze. Everyone knows how that ended.

“People have short memories,” says Myhre, who’s been in the business in Portland for more than two decades. “Every cycle will be overbuilt. It’s unfortunately a byproduct of the free market.”

When this current rush of multifamily housing does finally slow down, Portland will be a different place. In just a few years, apartment projects have transformed places like Southeast Division Street and some areas of North Portland into communities virtually unrecognizable from their former selves. Driven by market demand, building codes and a larger trend toward urbanization and inner-city living, these projects have brought high-density residential and retail destinations to neighborhoods that have historically been dominated by single-family homes and smaller multifamily dwellings. They’ve brought neighborhood standoffs, too, but also led to some compromises and tweaks to the codes that guide development in the city.

The new neighborhoods in the works — the 16 Lloyd District blocks that will be developed starting with Hassalo on Eighth, or the 20 blocks of the Con-way property in Northwest — will also alter what those areas have been for decades past.

The new crop of buildings is just the latest chapter in Portland’s ongoing evolution. The city is expected to continue to grow at a steady clip, adding another 205,000 people by 2035, according to Metro. Those people will need places to live, and many of them will want places that are conveniently located, close to transit, and near the restaurants, bars and shops that give Portland its signature flair, — the kinds of places that are reshaping the city landscape today.

The building boom — outside Portland

It’s not just in Portland that market demand and urban lifestyles are spurring new multi-family development.

The continued expansion of Intel and Nike is also triggering community transformation in suburbia. Vancouver developer Holland Partners has built close to 600 units in Wilsonville in the past few years alone and aims to complete 177 of 304 apartments at Tessara at Orenco Station in February. It’s also got hundreds of units planned for the $120 million Platform District, an urban district in Hillsboro centered around a public plaza, ground floor retail and a light rail stop.

“What we’re trying to do is build an urban node in a suburban location,” says Gary Vance, development director for Holland.

Market conditions have improved enough to fuel robust multifamily construction in other Oregon cities. In Bend, where residential construction dried up during the recession, Lake Oswego businessman Mike Kelley is building Sage Springs, a $10.2 million, 11-building complex of 104 units, and investor Craig Studwell has proposed a 144-unit project in southeast Bend. Vancouver’s Hoviss Development Group has also proposed a Bend development called Aspen Heights to include 473 upscale residential apartments.

Hoviss and Portland developer BPM Real Estate Group are behind a massive, $70 million building project in Eugene known as the Riverwalk Apartments. The 466-unit development, currently under construction, will include an assisted living center and an array of retail offerings.