Oregon’s Right to Repair law, signed into law this spring, could have a big impact on small repair shops.

Mark Gibbs’ family got their first computer when he was about 10. They lived in a small town in southern Oklahoma, and the nearest computer store was an hour and a half away in Oklahoma City, leaving them largely on their own if something went wrong. Gibbs started learning to use and fix computers, mostly teaching himself, then learned about them more formally in high school and at Murray State University, where he received a degree in information technology.

In 2009 he started a repair business called BrainWave Computers; it’s had a physical storefront in Beaverton since 2017. Much of his business comes from residential customers bringing in computers or other devices — Gibbs briefly paused our in-person interview in April to answer an employee’s question about a gaming system — but he also has some bigger, regular clients. They include smaller school districts, nonprofits and businesses that aren’t eligible for big tech-

support contracts.

“Working with tech and working with people are the two things I’m really passionate about,” Gibbs says.

Fixing electronic devices has come with a special set of problems and obstacles since at least the 1990s, when home computers became inexpensive enough — and easy enough to use — that most homes had them. The relative low cost and the speed of technology meant that in many cases, it was cheaper to replace a broken computer with a newer, faster one than to get it fixed. The same forces that made that possible also applied to other electronics — like stereos or small appliances — more generally. And often, replacement parts aren’t available, are hard to find or are prohibitively expensive.

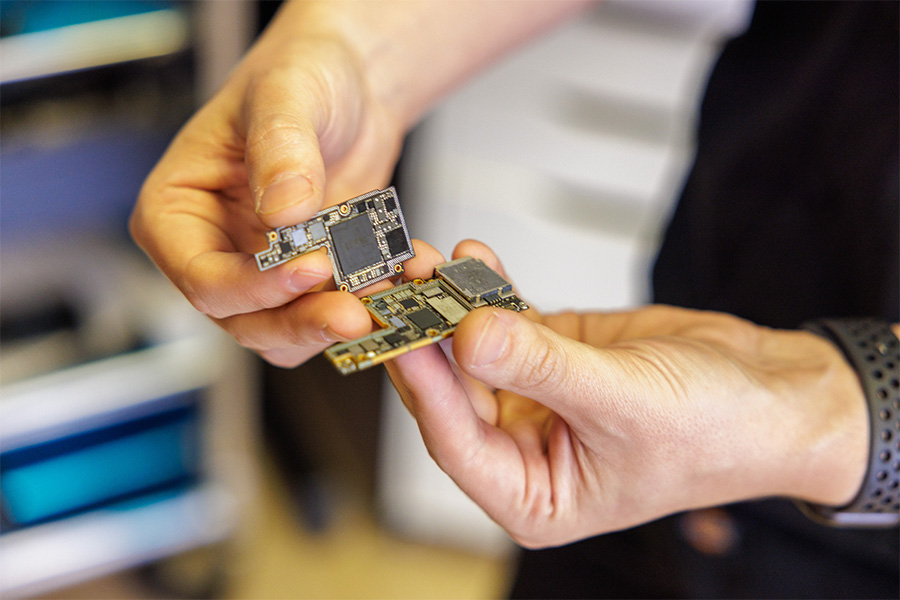

And that’s not even the worst of it. Even if one can get the right parts, they may not work properly, due to a practice called parts pairing — creating software locks on the parts that come with a device that mean they can only be used with that specific device and won’t function if transferred to another device.

In other words, the manufacturer “has to bless the repair,” says Romain Godin, whose repair shop, Hyperion Computerworks, is situated in Southwest Portland.

“We can buy two iPhone 13s new from the Apple store and switch the batteries, and you’ll get a bunch of messages saying, ‘We can’t tell if this is genuine,’” Godin says.

That means people who use Apple products need to go to Apple-authorized repairers to get their devices fixed — even when the repair is as simple as swapping out a battery or screen.

While Apple has become notorious in recent years for parts pairing, there’s a similar practice in car manufacturing called “VIN locking,” and manufacturers of kitchen appliances have also begun pairing parts with serial numbers, making it harder to make simple repairs.

According to Godin, manufacturers say they do this to prevent counterfeiting, but he thinks there would be fewer counterfeit parts on the market if companies made replacement parts readily available to customers and to business owners like himself, and provided more support for repair.

It’s created a situation where it’s often easier for customers to dispose of and replace electronic devices rather than replace them.

But the tide is turning.

Earlier this year, Gov. Tina Kotek signed Senate Bill 1596, which requires manufacturers to make the same documents, parts and tools available to the owners of consumer electronic equipment that they make available to authorized service providers for repair, maintenance and troubleshooting.

At least three other states have passed similar bills in recent years — notably California, which passed a Right to Repair bill in 2023.

Oregon’s law is notable, though, because it was the first to take direct aim at parts pairing. Under the law, manufacturers may not use parts pairing to prohibit an independent repair provider or device owner from installing or enabling the function of an otherwise functional replacement part or component of consumer electronic equipment.

The bill goes into effect Jan. 1, 2025, but enforcement doesn’t start until 2027, at which point consumers will be able to complain to the attorney general’s office if they believe a company is in violation. If the office finds a company is in violation, it can impose a civil penalty up to $1,000 per day as the violation continues or enjoin the company to restrain the violation.

“We wanted to make sure that as we see other policies that have come into play, and as we put this language together, that we were allowing companies to make potential changes to their process so that they can be good actors in this,” says Sen. Janeen Sollman (D-Forest Grove). “This was never set up as a gotcha. We wanted to make sure that we were good partners in this process.”

The bill passed 42-13 and enjoyed broad bipartisan support, with Republican Sen. Kim Thatcher, R-Keizer, co-sponsoring the bill.

Republicans got on board once they saw that much of the business community was on board, Sollman says. One big supporter was Google, which described the measure as “a win for consumers who are looking for affordable repair options, for the environment, and for companies that want to invest in making their products more repairable and sustainable,” per a statement from Steven Nickel, Google’s devices and services director of operations.

But even as the coalition of supporters broadened, Sollman says, the parts-pairing language remained an important sticking point. So Apple — which supported California’s Right to Repair legislation — did not follow suit when Oregon’s law was introduced, likely due to the parts-pairing language.

“Parts pairing was such a sticking point because I felt that if we eliminated the language that we had in the bill, it would essentially provide Apple the lane in which they could continue doing the practices that they do, which to me was very anticonsumer behavior,” Sollman says.

The current push to support tech consumers’ right to repair and to push back against manufacturers’ restrictive practices dates back to 2013, when the Digital Right to Repair Coalition — now known as the Repair Association — was formed in response to trends in electronics manufacturing. Manufacturers had stopped selling replacement parts or even making manuals available, and blocked customers and independent repairers from getting access to already installed firmware.

Oregon was actually the first state to introduce Right to Repair legislation, in 2019. That bill died in committee, and two subsequent attempts to introduce a Right to Repair bill also failed. Oregon’s current effort was led by the Oregon State Public Interest Research Group, which built a coalition of support including Hyperion and BrainWave, as well as environmental organizations like the Oregon Environmental Council and governments like Oregon Metro and the League of Oregon Cities.

In the interest of full disclosure: I worked for one of the organizations in the coalition, Free Geek, in 2005 and 2006, and have in recent months volunteered for two others — SCRAP PDX and Repair PDX — as a sorter of donated craft supplies and repairer of clothing. That is to say, I was not involved in the Right to Repair campaign, but my brief tenure at Free Geek piqued my interest in the problem of electronic waste. Electronics aren’t easy to recycle, and if disposed of in trash, they can leach toxic metals like mercury, lead and cadmium into soil and water. OSPIRG estimates that Oregonians dispose of about 4,800 cell phones every day, and that 85% of the energy and climate impact of cellphones is from the manufacturing process. So prolonging the life cycle of cellphones — not to mention computers and tablets — stands to have a real environmental impact.

Since the passage of Oregon’s bill, Colorado has passed a Right to Repair law that also includes language prohibiting parts pairing — and includes language specifically mentioning wheelchairs and farm equipment, which are increasingly subject to similar restrictions on repairs.

Oregon’s law includes some exceptions: It doesn’t apply to video- game consoles, medical devices, HVAC systems, devices powered by combustion engines and energy- storage systems.

In addition to fixing computers, Gibbs refurbishes and sells used computers and recycles them — it’s the best way to teach interns how computers are built, he says — and is hopeful that the recent wave of legislation will impact not just the way electronics can be fixed but the way they’re made.

“It’s definitely nice to have something that’s on our side rather than having to figure it out on our own,” Gibbs says. “I really hope it improves the relationship between repairers and manufacturers.”

Rigoberto Martinez, the three-year employee of BrainWave who asked Gibbs a question about PlayStation controllers, told Oregon Business he was a strong supporter of Right to Repair and a climate activist. He’s hopeful that the law will make it easier for do-it-yourselfers to access the right documentation, and to keep products out of landfills and recycling facilities for longer periods.

“If we can’t reduce, then at least reuse,” Martinez says.

Godin says the new law is a win for just about everybody.

“It’s better for the consumer, better for the environment,” Godin says. “The only people it doesn’t benefit are shareholders of the [big tech] companies — and I’m sure they’ll be fine.”

Click here to subscribe to Oregon Business.