The report says pharmacy benefit managers are able to conceal prices from the Oregon Health Authority through non-disclosure agreements between other entities in the states complex Medicaid network, and recommended fixes.

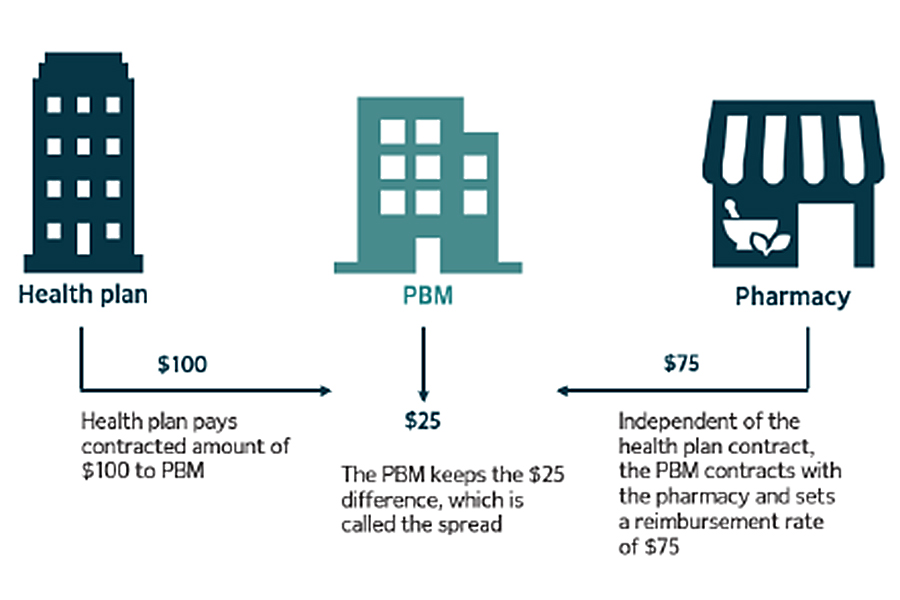

The Oregon Health Authority’s is unable to track and monitor Medicaid prescription drugs prices charged by pharmacy benefit managers, third-party intermediaries between insurers, drug manufacturers, pharmacies, and governments, according to a report published Monday by the Oregon Audits Division, a division of the Secretary of State’s office.

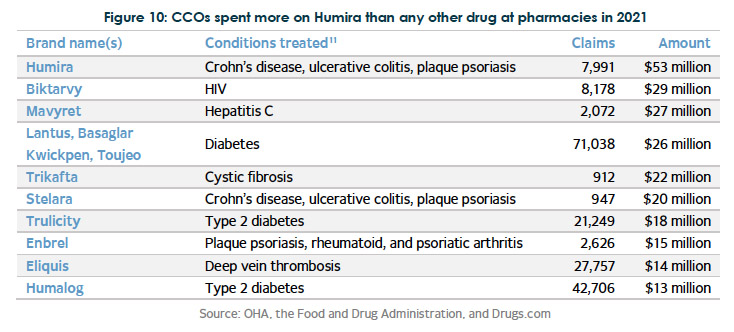

The OAD report was unable to estimate exactly how much the state has overpaid PBMs for prescription drugs, but noted national chains, some of which are owned by PBMs or PBM parent companies, were reimbursed twice the amount independent pharmacies were for selected drugs.

“Pharmacy Benefit Managers have proprietary deals with drug manufacturers and we do not know the true net price after rebates and discounts from those manufacturers,” Ian Green, the audit manager who oversaw the report, tells Oregon Business over email.“OHA needs to monitor six PBMs across 16 different CCOs and each CCO has a different deal with those PBMs. Each pharmacy also has a different deal with the CCOs and PBMs and different reimbursement structures. Preferred drug lists for example may change quarterly or monthly for each of the CCOs and there are many other factors that make this regulation and oversight different for OHA.”

The audit division’s 55-page report titled “Poor Accountability and Transparency Harm Medicaid Patients and Independent Pharmacies” found PBMs are able to conceal pricing through non-disclosure agreements with Coordinated Care Organizations and other entities they interact with up the supply chain.

“The deals PBMs negotiate with insurers, manufacturers, pharmacies, and other entities are often considered trade secret information and do not have to be shared. This opaque system makes it impossible to understand the actual costs of prescription drugs and has garnered attention at multiple levels of government,” the report reads.

While unable to provide exact figures, the report noted that in 2021, about 11.8 million Oregon Medicaid prescriptions were dispensed at pharmacies, and CCOs reported spending $767 million on prescription drug benefits, while Fee-for-service drug expenditures were only $208 million.

The report called Oregon’s Medicaid system the largest and most complex government program in Oregon, The state’s prescription drug process in Medicaid involves multiple entities interacting, including sixteen COOs, six PBMs, hundreds of pharmacies, multiple drug manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacy administrative organizations, the OHA and the Department of Consumer and Business Services.

Historically, PBMs were created as claims processing administrators to help insurers contain drug spending. Currently, three largest PBMs control 80% of the U.S. prescription market complex web of prescription drug billing and generate $315 billion annually. PBMs can influence which drugs are covered by insurance companies and whether certain prescriptions can only be filled at specialty pharmacies.

PBMs have already faced federal regulations for their ability to control drug prices. In in 2018, the Patient Right to Know Drug Prices Act, S.2554 and the Know the Lowest Price Act, S.2553 banned “gag clause” provisions between PBMs and pharmacies, which prevent pharmacists from telling patients when the cash price of a drug is less than the insurance copay price.

The report details a number of best practices that other states have implemented and makes recommendations where it believes Oregon should adopt policies to regulate PBMs. One particular model Green says other states have found success was adopting a single PBM for their entire Medicaid program. Another model Green suggested would be a universal a fee-for-service model for all prescription drugs in the state. Other states require PBMs to be a fiduciaries, which means they must act in the best financial interest of the state and Medicaid patients.

He says other states that have adopted these models have reported hundreds of millions of dollars in savings.

“It’s always important we make sure taxpayer funds are being spent as effectively as possible, and Medicaid is a prime example,” said Audits Director Kip Memmott in the press release accompanying the audit. “It’s the largest and most complex government program in Oregon and provides critical health services to more than one million Oregonians. But the lack of transparency in our current system means it’s almost impossible to tell if we’re truly getting the best use of our funds with these PBMs.”