Large swaths of Oregon’s public land are being leased for wind exploration, leaving wildlife at risk and raising serious questions about how energy projects should be developed.

Large swaths of Oregon’s public land are being leased for wind exploration, leaving wildlife at risk and raising serious questions about how energy projects should be developed.

By Lee Van der Voo // Illustrations by Ana Mouyis

The exact speed of the wind on this flat-topped butte is confidential. But on the towering plateau 32 miles east of Bend, wind whips across the sagebrush at 5,000 feet, piling snow up by the foot in winter. It’s a landscape mostly left to sage grouse and eagles, pygmy rabbits and bats. Increasingly in Oregon, such lands are also welcoming new residents: windmills.

The exact speed of the wind on this flat-topped butte is confidential. But on the towering plateau 32 miles east of Bend, wind whips across the sagebrush at 5,000 feet, piling snow up by the foot in winter. It’s a landscape mostly left to sage grouse and eagles, pygmy rabbits and bats. Increasingly in Oregon, such lands are also welcoming new residents: windmills.

Pacific Wind Power, owned by 69-year-old John Stahl of Santa Barbara, plans construction of a 104-megawatt wind farm on West Butte. The company is still pursuing financing for the project, but when its 52 wind turbines start turning, Stahl hopes next year, a 4.5-mile road will reach across federally managed land from Highway 20, making it one of two wind projects to lease public lands in Oregon. On the new frontier of renewable energy, this is our pioneer.

Driven to the butte by a federal policy that makes renewable energy a priority for public lands — a silver bullet intended to address climate change, energy independence and job creation in one — it comes with blessings from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. The agency’s effort to help developers, state and local governments, and landowners develop wind farms and solar arrays nationwide was sanctioned by an Interior Department order in 2009, aiming to put 10,000 megawatts of renewable energy leases on national public land by the end of 2012.

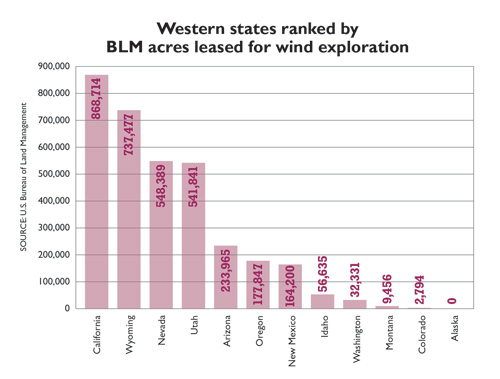

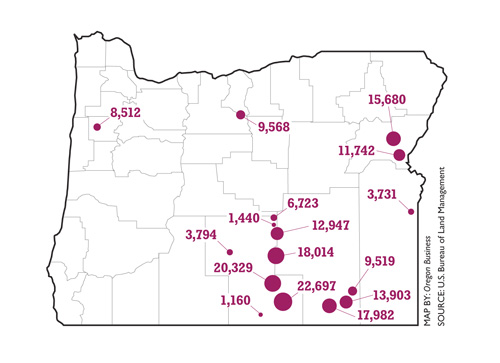

But conflicts with existing residents of the land — birds and bats primarily, along with cattle-grazing ranchers and hunters — are an unfortunate result. With a mandate to site renewable energy projects, but no real rules as to how, it falls to conservationists, government officials and others to define where renewable energy will fit into public lands in Oregon, even as 177,847 acres are currently being studied or developed for wind farms.

This pursuit on Oregon lands is part of a national trend. So far, the race to the 10,000-megawatt finish line includes hopeful plans for 12,500 megawatts in solar projects (about 100,000 acres) in the nation’s southwest.

This pursuit on Oregon lands is part of a national trend. So far, the race to the 10,000-megawatt finish line includes hopeful plans for 12,500 megawatts in solar projects (about 100,000 acres) in the nation’s southwest.

In Oregon — blessed with windy gorges and ridges and cursed by limited transmission in the sunny south — it is wind that is the advancing force. That flat, breezy places along the ready-wired Columbia Gorge are locked up has pushed companies east of the Cascades. There, much of BLM’s 15.7 million Oregon acres are singing opportunity. Wind developers were sleuthing conditions on 177,739 acres in mid-October, testing for possible development. Meanwhile, construction was wrapping up on the first wind farm to be built, the 3.5-megawatt Lime Wind project in Baker County.

In the 12 Western states with lands managed by BLM, there are 47 wind farm proposals on 384,722 acres. Another 169 sites are being tested for wind speeds, 16 in Oregon, making the state the sixth most active for wind development. Projects are under construction on 33,632 public acres nationally. In addition to the recent approval of the West Butte Wind Power Project’s access road and Lime Wind, Spain-based EDP Renewables (formerly Horizon Wind Energy) envisions a 500-megawatt wind farm on Burnt River. The company also plans another wind farm on Pueblo Mountain. Oregon Community Wind, a Portland-based developer focused on small-scale projects, is pursuing a 9-megawatt farm 15 miles east of Lakeview.

“There’s been a rush on developing alternative energy and cashing in on incentive markets,” says Brett Brownscombe, natural resource policy adviser for Gov. John Kitzhaber. But while development moves forward, the rules for siting wind projects, particularly in sensitive habitats, are being made up as projects move along, prompting concerns about whether resource protections for wildlife will keep pace.

In 2009, former Gov. Ted Kulongoski convened a group under the Oregon Solutions umbrella to reconcile the call for energy leases with the state’s energy and wildlife priorities. That conversation continues today, involving seven government agencies and other stakeholders.

“As we continue to think about renewable energy and the need for transmission facilities that will go with that, do we want to continue mitigating on a site-specific basis?” asks Pete Dalke, an Oregon Solutions program manager who coordinates the meetings. “Or do we want to look across Eastern Oregon and look at whether there are key areas of habitat that we want to build upon by preserving it and restoring it and expanding on it?”

Bringing wind farms to the West hasn’t been as simple as federal officials might have imagined. Spinning blades are proving deadly to golden and bald eagles, prompting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to temporarily halt construction of wind farms nationally, including West Butte and three others in Oregon, and to review operating farms last fall while crafting an eagle protection plan.

Bringing wind farms to the West hasn’t been as simple as federal officials might have imagined. Spinning blades are proving deadly to golden and bald eagles, prompting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to temporarily halt construction of wind farms nationally, including West Butte and three others in Oregon, and to review operating farms last fall while crafting an eagle protection plan.

Cattlemen are cautiously watching wind development, supportive so long as energy leaves room for grazing allotments, according to rancher John O’Keeffe, public lands committee chair for the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association. Hunters and conservationists are looking to preserve populations of mule deer, elk and other wildlife. Of particular concern is the sage grouse, a now imperiled species of bird that dwells on the same flat, open lands also prime for wind farms.

Sage grouse breed in open spaces called leks, and will avoid them, and breeding, if tall objects hover, fearful they conceal predators. With the number of leks shrinking and no way to reproduce them, sage grouse were categorized as “warranted but precluded” by the U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife in March 2010, meaning the bird’s condition warrants an endangered species listing but there aren’t the resources to make it happen. The listing was a cautionary signal to developers and conservationists. If sufficiently harmed by wind farms, sage grouse could prove the spotted owl of Eastern Oregon and wipe out energy goals for some states altogether, including Oregon.

Bob Sallinger, conservation director of the Audubon Society of Portland, is among conservation leaders looking critically at wind. While the last two years of planning and talks have led to bald and golden eagle protections, a BLM effort to protect sage grouse regionally, and a mitigation and sage grouse protection policy for Oregon, Sallinger says those are bright spots on an otherwise troubling scene: Oregon still doesn’t have a framework for determining where wind farms can go. And the political pressure to put more renewable energy on federal land — and do it fast — may meanwhile have consequences for wildlife.

“We haven’t seen that federal agencies so far are willing to stand up to wind developers and really ensure that natural resources are protected,” says Sallinger. “Ultimately, I think that’s not only going to be to the detriment of natural resources but to the wind industry itself, because what I see is that the wind industry is losing its green veneer.”

But speaking out is an awkward posture for some conservationists, many of whom championed renewable energy as an answer to climate change. Sallinger says conservation groups first avoided such disputes, glad to make progress on alternative energy goals.

“I think what you’re seeing now is a growing shift from focusing on ‘OK, we need to be doing this’ to ‘we need to be doing it right,’” he says. “I think it’s important to understand that the market that drives renewable energy is not entirely different from the market that drives oil.”

John Audley, deputy director of the Renewable Northwest Project, a Portland-based nonprofit focused on growing renewable energy generation, sees possibilities, however, for renewable energy to be a positive force on the landscape. While conservation dollars are short, he says the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife could use funds from renewable energy mitigation to underwrite conservation efforts. “I’m not arguing for bad decisions in the interest of renewable energy investments, but if true partnerships exists,” he says, then those opportunities should be forged.

John Audley, deputy director of the Renewable Northwest Project, a Portland-based nonprofit focused on growing renewable energy generation, sees possibilities, however, for renewable energy to be a positive force on the landscape. While conservation dollars are short, he says the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife could use funds from renewable energy mitigation to underwrite conservation efforts. “I’m not arguing for bad decisions in the interest of renewable energy investments, but if true partnerships exists,” he says, then those opportunities should be forged.

West Butte is one example, with Pacific Wind Power providing $1.3 million for restoration and enhancement of 9,000 acres of sage grouse habitat and conservation easements. Through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the company will also spend $40,000 a year for the life of the project, 20 to 25 years, to spread cages on power poles to prevent electrocution of eagles.

Criticism that wind development in these areas could ultimately resemble extraction industries like oil and gas hit hard among developers. Pacific Wind Power’s Stahl, the West Butte developer, is among them. Having shifted careers to wind development after 14 years focused on problems posed by oil tankers and liquefied natural gas in Santa Barbara County, he is particularly galled at the suggestion.

“I don’t understand how it would be extraction of the land, we’re not depleting anything,” he says. He notes that wind has a much smaller footprint than solar, and that in a state like Oregon, where approximately 53% of the land is publicly owned, “It ought to be used for something instead of just cattle grazing.”

That wildlife issues are most prevalent in the same rural communities hardest hit by economic downturn hasn’t been lost in the discussions. Though BLM maintains no national statistics on how many jobs wind projects create, it’s also clear wind farms bring work to areas most in need of economic boost. The West Butte Wind Power project is expected to generate 70 jobs during construction and another 345 to provide supplies, materials, support and offsite services to construction workers. The American Wind Energy Association pegs long-term jobs in wind at 21 jobs per 100 megawatts.

As developers consider public lands, some, including Roby Roberts, vice president of communications and government affairs at EDP Renewables, say the process is still too complicated for good business. Even amid signals of support from the highest levels of government, Roberts says resources in local BLM agencies are slim, and that the Department of Interior hasn’t kept federal agencies organized in moving development forward. “We wish they were more coordinated, we wish they were more collaborative. And this process has not been as smooth as we would like,” he says.

Randy Joseph, the owner of Lime Wind, says seeing that project through meant navigating a confusing federal bureaucracy. “There is no one person to make a decision. There’s nobody to go to and get a definitive answer. Sometimes that is frustrating,” he says. Oregon Community Wind’s Big Valley Wind Project east of Lakeview stalled out for eight months when the nearby Ruby Pipeline riled tribes, squeezing resources at the small business. “We don’t have 30 projects out there that are constantly churning. It really affects us,” says CEO Kirk Slack.

Still, Audley says, “I don’t think we can walk away,” even if wind developers continue to emphasize private land while obstacles remain.

“If you want to call [the Columbia Plateau] low-hanging fruit, it’s been picked,” he says. “That means we venture from places where the choices were easy and clearer to areas where there are conflicts, and we need the kind of values to muscle through difficult situations.”

He believes renewable energy development on public lands is a critical part of the nation’s

energy future.

Yet as long as wind developers are a small part of the energy picture, they will continue to compete for staff attention and predictable policy at BLM. Though the agency anticipates national wind leases to account for $2.9 million by 2016, it’s a paltry sum, and a demonstrably small part of the energy business at BLM, where right-of-way rentals for oil and gas pipelines, leases, bonuses and royalties across the country totaled $13.7 million in 2010. Competitive oil and gas lease sales show comparably monstrous returns: the 25 sales held so far in 2011 netted $193 million.

Such slow traction on renewables has allowed time for talks in Oregon about where and how wind can make the most of its potential in the state. Which resources are best set aside for traditional uses, both by ranchers and by wildlife, particularly sage grouse, likely will be a continued — and heated — debate for many more years.

Lee Van der Voo is a Portland journalist who has written for The New York Times, The Atlantic, and other noted publications. Her last story for Oregon Business was on the stalled wave energy industry. She can be reached at [email protected].