An old sign, discovered in an antique shop, hangs over the front of Dr. George Brown’s desk: “A deposit of $5 is required on all hospital cases.” Brown is prone to hypotheticals, as in “if I knew the answer to that” and “if I had a dollar for every meeting I went to.” So one such as “if a hospital visit were $5” amuses him.

An old sign, discovered in an antique shop, hangs over the front of Dr. George Brown’s desk: “A deposit of $5 is required on all hospital cases.” Brown is prone to hypotheticals, as in “if I knew the answer to that” and “if I had a dollar for every meeting I went to.” So one such as “if a hospital visit were $5” amuses him.

|

TACTICS: THE GOOD DOCTOR

STORY BY ADRIANNE JEFFRIES // PHOTOS BY KATHARINE KIMBALL

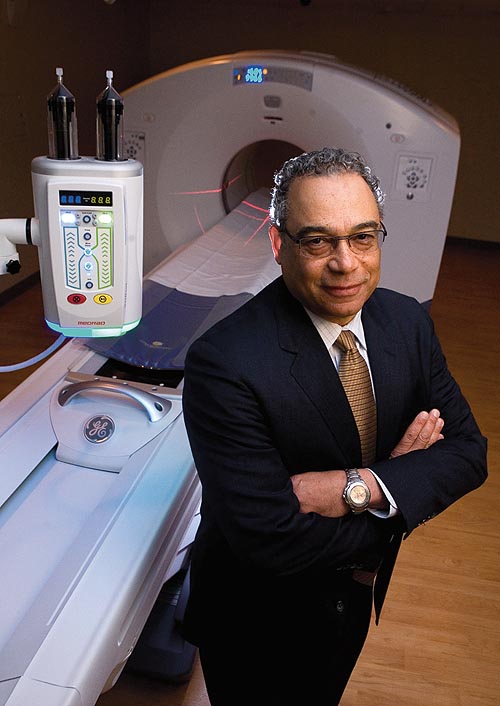

An old sign, discovered in an antique shop, hangs over the front of Dr. George Brown’s desk: “A deposit of $5 is required on all hospital cases.” Brown is prone to hypotheticals, as

in “if I knew the answer to that” and “if I had a dollar for every meeting I went to.” So one such as “if a hospital visit were $5” amuses him. Five dollars would probably be more like$100 today, depending on when the sign was made. But the reminder that hospital care once cost so little and paying for it was as simple as putting down a deposit contrasts starkly with the expensive and complicated system we have now.

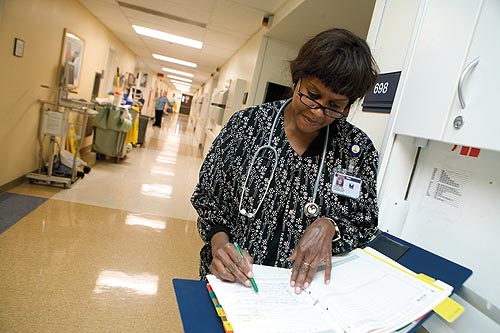

Legacy Health is a nonprofit with six hospitals in the Portland area. Brown is the first CEO it’s ever had who is also a doctor. He’s 62 and a 26-year veteran of the Army, where he practiced medicine. Legacy employees speak of him warmly. “He’s a listener,” says one.

Brown has been preparing Legacy for health care reform since just before the 2008 election, when he took over as CEO. Oregon’s hospitals were struggling with unpaid bills, underpayment by Medicare and Medicaid, and the cost of free care to the needy, which amounted to almost $1 billion in 2008. The financial crisis slashed hospitals’ assets and made it tough to get loans as the number of patients who were unable to pay kept rising.

Preparing for health care reform meant more than talking to Congress and switching over to electronic records. Brown is co-chair of a task force of Oregon health care professionals that has produced innovation and cost savings in administration, payment and treatment. He’s also a strong proponent of an experiment in primary care that improves patient and staff satisfaction and quality of care and will hopefully cut costs: the patient-centered medical home.

|

Imagine having a regular team of doctors, nurses and medical assistants in your neighborhood who know all about you, your medical history, your diet and when you’re due for a mammogram or a prostate screening. “Medical home” has different definitions depending on whom you ask, but the common threads are data, continuity and proactive care. Legacy has five medical homes — the first opened in 2007, and the newest opened last year. The medical home “wraps its arms around a population,” Brown says, so medical homes can tailor services to their patients; Legacy’s Good Samaritan medical home has enough elderly patients to merit three geriatricians and a geriatric psychiatric nurse practitioner. The hope is that medical homes will cut costs by diverting patients from the emergency room and catching problems early.

Payment reform is key to the medical home experiment. Traditional insurance only pays for certain things; it might pay for a doctor to explain in five minutes a medication you’ve already been taking for years, but not for a 20-minute conversation with a nurse about how to improve your diet. By contrast, Legacy’s medical homes receive a flat fee per patient from the Oregon Health Plan, CareOregon. They’re also paid based on quality measures such as whether patients get timely appointments — something that will become more common as health care reform phases in.

There are other medical home-type clinics in Oregon, but Legacy’s serve a wide range of patients, including commercially insured, Medicare and Medicaid patients, older patients, and patients with HIV. And Brown wants to open more. He’s partial to a single-payer model like the military’s. But medical homes, even if they’re multi-payer (some medical homes aren’t), are a vast improvement over what we have now. The next step is to make them profitable — Legacy’s medical homes are supported by grants.

Medical homes are a part of the future of health care, Brown says. But health care reform will take at least a decade and the churning has just begun. Some parts of the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act don’t come into play until 2018, although the first rules will take effect this month. Brown’s priority is to keep himself and his staff engaged during what he calls “a stressful time” for hospitals. With reform coming from Congress, the state and the private sector, the ramifications are not fully known, except for one: Change is happening.