“SpeakEasy” is a third-year German course at Portland State University conducted as a student-run business startup company. Speaking in German and French, students are in charge of a small business that designs, manufactures and sells multilingual greeting cards.

“SpeakEasy” is a third-year German course at Portland State University conducted as a student-run business startup company. Speaking in German and French, students are in charge of a small business that designs, manufactures and sells multilingual greeting cards.

|

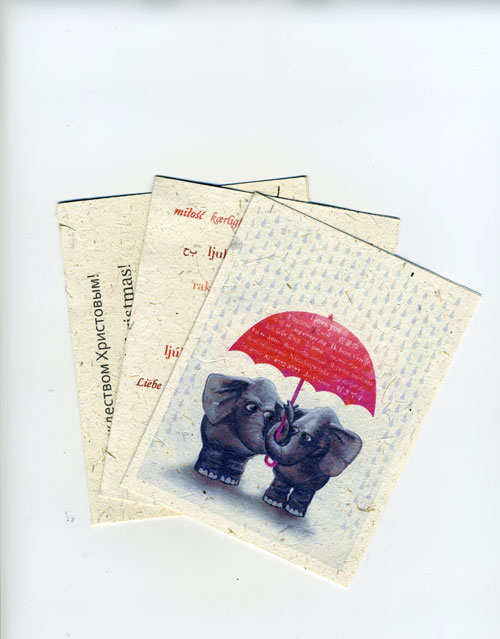

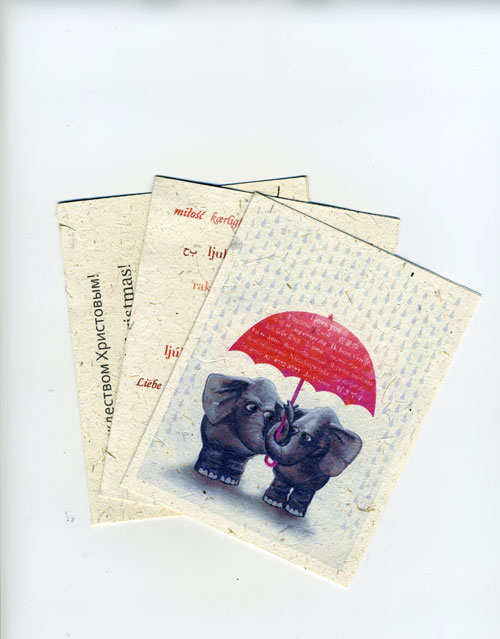

Cards made by SpeakEasy students. |

Sixteen Portland State University students sit in a classroom, taking notes as German professor Bill Fischer details the day’s assignment in German and professor Maggie Elliott retranslates in French. Fischer tells the students that during their presentations for the class’s annual Exposition and New Product Rollout there needs to be a “high point” in their speeches to capture audience attention.

Student Brett Condron questioned the idea of incorporating excitement into the presentations, saying speeches about sales and marketing strategy can’t help but be boring. “Have you ever seen a shareholder meeting?” Condron asks.

“But we’re a small, hungry firm,” Fischer responds.

This isn’t just any foreign language class. Fischer calls the class “SpeakEasy.” It’s a third-year German course conducted as a student-run business startup company. “This is far more difficult than putting verb charts on a board,” Fischer says.

Speaking in German and French, students are in charge of a small business that designs, manufactures and sells multilingual greeting cards. Their products include Valentine’s Day, Christmas, birthday and thank-you cards that are printed on paper made from recycled elephant dung. Their message is expressed in all 23 languages taught at PSU, plus Dutch, and the cards cost between $1.50 and $3.

Business is booming.

“We’ve already exceeded everything we thought was practical,” says Condron, who is the equivalent of the company’s chief financial officer.

The class sells the cards once a week from an on-campus booth. Sales during the spring academic quarter (about half completed) are at $600. “Since we have a real presence, more people have been finding out about us,” Condron says.

Students first sold cards to friends and family. “It was like being a new Avon sales representative,” Condron says.

Fischer began the class in 2001 when he incorporated business and occupational language into a third-year German course and decided to craft the class into a workplace environment. It took seven years to develop a product.

The first was small, portable vocabulary cards packed in plastic carrying cases, with early capital between $750 and $1,000 coming out of Fischer’s pocket. “Quality control was horrendous,” Fischer says.

The class switched to producing cards in 2009. A student suggested using a sustainable paper product, which Fischer says amounted to instant advertising. “There was an immediate return,” he says.

Sales increased by 600%. Production has doubled as marketing efforts increased in late February, and Condron hopes that in two years sales will increase to $10,000 per quarter.

There’s more at stake than gaining practical language skills. Foreign language programs are getting cut from university department offerings because of budget cuts and the perception that foreign languages are not useful.

Fischer hopes that part of the profit can help lessen the impact of institutional budget cuts. “We’re frightened that German [classes] won’t survive if we don’t adapt to the times,” Fischer says.