When Kristofer Lofgren decided to brand his new sushi restaurant “sustainable,” he knew he’d need to fight the perception that environmental consciousness comes with a higher price tag.

When Kristofer Lofgren decided to brand his new sushi restaurant “sustainable,” he knew he’d need to fight the perception that environmental consciousness comes with a higher price tag.

|

When Kristofer Lofgren decided to brand his new sushi restaurant “sustainable,” he knew he’d need to fight the perception that environmental consciousness comes with a higher price tag.

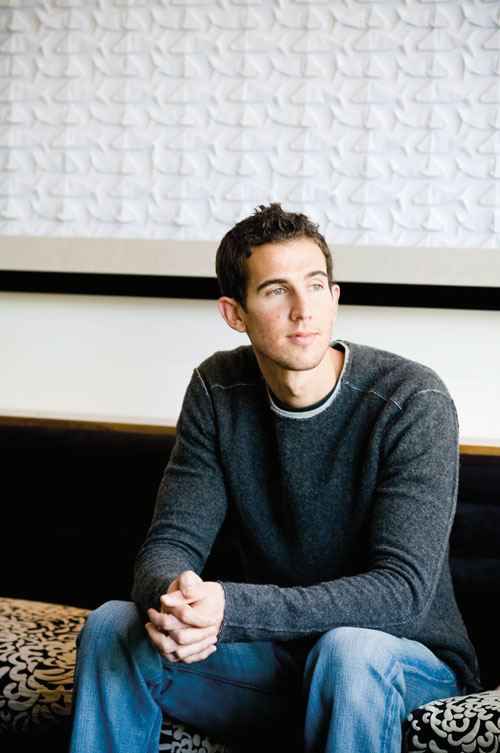

The 27-year-old restaurateur decided to open Bamboo Sushi in Portland in the same location as Masu East sushi restaurant, which he co-owned before buying out his partner. He’d keep prices the same despite switching to a menu swimming with certified, environmentally sustainable fish, a decidedly more expensive product.

To make a profit, he’d simply need a higher volume of customers.

Easier said than done in a county with 3,400 restaurants, many of which vie for the Bamboo Sushi market: professionals in their 30s and 40s with a taste for fine dining.

And that’s not to mention the ongoing recession, which has made meals out seem more dispensable, especially those involving pricey raw fish.

Lofgren’s strategy was simple. He’d hook customers on their first visit.

“We wanted to create loyalty and trust through certification and sustainability, not necessarily more customers,” he says. “The trick is getting them to come back again and recommend us to a friend.”

He reasoned that for some, sustainability would be a draw, but for the most part, customers would return based on the quality of the food and service, as they would with any restaurant.

Bamboo is the first sustainable sushi restaurant to be certified by the Marine Stewardship Council, but Tataki Sushi and Sake Bar in San Francisco operates under similar principles.

|

|

|

|

Despite a rising sea of awareness about food sourcing, other restaurateurs don’t seem to see success with sustainable sushi, presumably because the sushi industry profits by serving inexpensive fish, much of which is caught using destructive fishing and farming practices. Lofgren witnessed that reality as a partner in Masu East, an investment he made as an undergraduate at UC-Berkeley. Upon graduation, Lofgren moved to Portland to study environmental law at Lewis & Clark, but decided he could effect environmental change faster in the business world.

For most customers “sustainable sushi” means little. Through table tents, menus, a website and servers schooled in the eco-ethics of the fish industry, the restaurant invites patrons to learn about the term.

Much of the restaurant’s fish is certified by the Marine Stewardship Council as non-endangered species harvested by environmentally friendly methods. And Bamboo doesn’t serve seafood that appears on the “avoid” lists of the Monterey Bay Aquarium and Blue Ocean Institute.

“Every fish can be tracked to the boat where it came from,” says the restaurant’s executive chef, Brandon Hill.

Getting that caliber of fish to Portland was one of the greatest challenges in opening Bamboo. Hill and Lofgren forged a relationship with Northwest seafood vendor Ocean Beauty Seafoods, which agreed to import sustainably certified fish in exchange for bulk ordering.

By purchasing nitrogen-frozen fish in quantity, the restaurant saves on high freight costs, a practice that shrinks its carbon footprint, Lofgren says.

Bamboo Sushi opened last fall amid an economic downturn that continues to push many Portland restaurants out of business. While Lofgren won’t disclose revenue figures, he says the restaurant has had successively more patrons each month.

Lofgren hopes the numbers become a step toward his ultimate goal: operating a sustainable business long-term. He recently visited Chez Panisse in Berkeley, the kind of 38-year-old, ecologically sound restaurant that inspires young restaurateurs to wax philosophical.

“They’re still doing something interesting and relevant,” he says. “The idea is not necessarily growth, but innovation and evolution.”