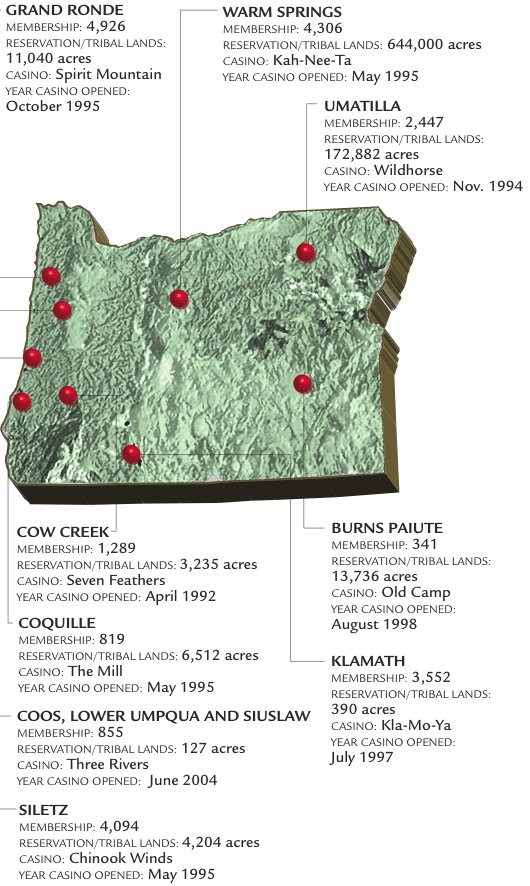

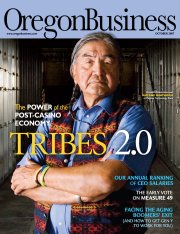

As the next decade unfolds, the nine federally recognized tribes in Oregon will have a major role in how the economy of the state develops. It’s not just about casinos anymore.

TRIBES 2.0

TRIBES 2.0

As the next decade unfolds, the nine federally recognized tribes in Oregon will have a major role in how the economy of the state develops. It’s not just about casinos anymore.

By Abraham Hyatt

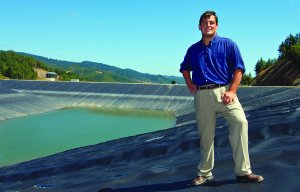

It’s a summer day in Canyonville about a half hour south of Roseburg, and the Cow Creek Tribe is pretending their new dam is about to collapse.

It’s one of the biggest dams in Douglas County: 1,000 feet long, 95 feet high and capable of holding back 119 million gallons of water. It spreads across the mouth of a canyon that sits above I-5 and several million dollars worth of tribal enterprises: the Seven Feathers casino, a motel, an RV resort, a truck stop, a restaurant and self-storage units. The drill spreads quickly via radio and cell phone from the base of the dam to the floor of the casino.

This is not the tribe’s only dam. Further back in the canyon sits a smaller companion dam. And another reservoir. And a gray-water lagoon. Nearby sits a water treatment plant, storage tanks, a sediment basin — all part of a $25 million, 250-acre utility project that, come this winter, will supply the tribe and, in emergencies, the city of Canyonville with water.

|

“Sewer, power, water: We’re working toward total self-sufficiency,” says Wayne Shammel, the Cow Creek’s lawyer, as he drives past workers involved in the drill on the dusty road that follows the rim of reservoirs.

The recently completed project was built on the success of the tribe’s casino and resort. And while the casino will remain its crown jewel for years to come, Cow Creek — like many tribes around Oregon and the nation — is rapidly moving beyond a gaming-based economy.

It’s a transition that requires quick learning. Fifteen years ago, Cow Creek was the only tribe in Oregon with a gaming facility. Now the tribe owns and operates 12 separate companies and is the second-largest employer in the county. Its members are learning the intricacies of running a municipality-sized utility. And the tribe is learning that its successes can draw political ire from the local community.

Their growth and push for economic diversity — also typical of other tribes in the state — shows no signs of slowing. Economists hired by the tribes say tribal gaming alone had an almost $1.5 billion economic impact on Oregon in 2005. But that’s just casinos. Last year the Coquille Tribe teamed up with Home Depot on a $20 million shopping center. The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation have attracted two Fortune 500 companies to a new business park a few miles outside of Pendleton. Smaller examples at other tribes abound.

When Antone Minthorn, chairman of the Umatilla board of trustees, says, “We are on the cutting edge of economic development in rural Oregon,” there’s evidence to back up that claim.

Oregon state economists have no estimates or data to determine what impact tribal economies as a whole have today. But it’s clear that as the next decade unfolds, Oregon’s nine federally recognized tribes won’t just be shaping the future of their children, grandchildren and culture. They’ll have a major role in shaping the economic future of the state.

OREGON TRIBES ARE NOT UNIQUE in their push to diversify. It’s a shift that some tribes across the country are making very successfully. Last year the Seminole tribe of Florida made international headlines when it announced it was buying the Hard Rock chain of casinos and hotels for about $965 million. The Southern Ute tribe in Colorado is worth nearly $4 billion, in part because it controls the distribution of roughly 1% of the nation’s natural gas supply. In Washington State, the Puyallup Tribe is replacing a riverboat casino in Tacoma with a $300 million international shipping container terminal.

|

Economists and the tribes agree that nearly all growth can be traced back to a 1987 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court, which decided that tribal lands did not fall under state gambling laws because of the sovereignty of the tribes. Consequently, they could build casinos. Using gaming money as a springboard, tribes bought and created businesses.

The same court first established tribal sovereignty in the 1880s. Despite that promise, the federal government spent the ensuing decades attempting to force assimilation on American Indians. In the 1950s, 109 tribes — 62 of which were in Oregon — were dissolved or had their land taken away. In Oregon, like many other states, it was the culmination of more than 100 years of forced relocation and land theft.

By the 1970s and 1980s, legal action, political pressure and sometimes-violent protest — along with a changing national attitude toward civil rights — led to a shift in federal and state positions. Through legal battles, some Oregon tribes regained federal recognition. Some received money for lost land. Some even had land returned to them. Employment and poverty rates were still tragically low. But now the tribes had a way to address that.

|

Four years after the Supreme Court’s 1987 gaming decision, the Cow Creek took out an $825,000 loan from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and built a tin-sided bingo hall. It was the first in Oregon, but not for long.

In 1994, the Umatilla opened a casino outside of Pendleton. The year after that, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians (Lincoln City), the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs (Warm Springs), the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde (Grand Ronde) and the Coquille (North Bend) all opened casinos.

Today, Oregon’s nine federally recognized tribes all have casinos.

In 2005 those casinos had a direct $675 million effect on Oregon’s economy, according to a study by the economic consulting firm ECONorthwest that was commissioned by the tribes. Add in the impacts to the construction, manufacturing, wholesale, retail and services industries and the number jumps to $1.47 billion.

That’s nearly the combined economic force of Oregon’s wine and dairy industries.

THE IMPACT OF TRIBAL ECONOMIES as a whole, versus simply the impact of casinos, is harder to quantify. Because the tribes are sovereign entities, the state doesn’t compile its own data, says Jill Mills, the national business development officer for the Oregon Economic and Community Development Department (OECDD).

Some tribes have done their own county-specific studies. The Cow Creek estimates it had a $142 million overall impact in 2006 in Douglas County. The Coquille says its businesses had a nearly $53 million impact in Coos County.

Many tribes, however, won’t reveal anything about their financial affairs. Until 2005, Mike Burton was assistant director at OECDD. Now he’s the director of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians’ economic development corporation. He says one reason for the secrecy is a fear that if communities begin to think that the tribes are flush with cash, they’ll shut down services or schools near tribal lands in hopes that the tribes will take up the slack with their own programs.

But even without hard data, it’s still possible to quantify some aspects of the effect tribes have on the state. One way is to look at the number of jobs created, almost all of which are in areas with high unemployment. According to state data, Oregon’s tribes employed 2,200 people in January 1995; in July of this year, the number was 8,700.

An equally important indicator, says Burton, is the scope of tribes’ economic investments. Along with the businesses that sit below their dam, the Cow Creek also own a communications company, a graphic design and marketing company, a lodge, a cattle ranch and hay operation, and Umpqua Indian Foods, where the tribe manufactures and sells jerky and gift items. They also run their own electric utility.

All that adds up to about 1,270 jobs. And it makes them the second-largest employer in Douglas County.

The Coquille own an assisted living and Alzheimer’s facility, the Mill Casino, a fiber-optic telecommunications company, and Coquille Cranberries, which they say is the world’s largest producer of organic cranberries. With the more than 600 jobs they provide, they’re also the second-largest employer in the county, paying an estimated $15 million in wages and benefits a year — wages that were 15% to 60% higher than those at comparable jobs elsewhere in Coos County, according to the tribe’s analysis.

The Grand Ronde is already the largest employer in Polk County with 1,500 employees. Several years ago it helped finance an office building in Portland. Now it’s teamed up with the Siletz on a $2.5 million business development project in Keizer. Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua & Siuslaw Indians — which didn’t build a casino until 2004 — don’t have any major investments. But they estimate that an upcoming expansion to the casino will create 250 more jobs in the town of Florence, population 8,000.

On the other side of the state, the Umatilla own the Wildhorse Casino, a truck stop, an energy company, a market, a golf course and a recreation area. In the last year, the tribe has partnered with DaVita Inc. to build a kidney dialysis center and with the international outsourcing company Accenture to create Cayuse Technologies — a tech business with software programming, digital document processing and a call center. Both will open this year.

Of the Umatilla’s $145 million 2007 budget, the tribe says that less than 20% of revenue comes from casino profits; the rest comes from grants, contracts, interest earnings, utility taxes and funding from the state and federal governments.

Between their own government and businesses, they employ 1,135 people with a $35 million annual payroll. They, too, are the second-largest employer in their county. And the 250-plus jobs that Cayuse Technologies will create — tribal leaders say the jobs will pay more on average than other area jobs — may take them to the No. 1 spot soon.

“We’re not looking to have an empire here,” says Stephanie Seamans, one of the Umatilla’s economic planners. “But we want an economic base so that at some point our unemployment rate is the same as everywhere else or lower.”

That’s no small thing on a reservation where unemployment stood at 37% just 15 years ago. And it’s no small thing in a state where seven years ago 26% of American Indian families earned less than $25,000 a year.

Seamans is beginning to get her wish: Since the 2000 census, the number of American Indians in Oregon living below the poverty rate dropped 23%, and the number of tribal members going to college has increased 88%.

THE TRIBES’ ABILITY TO BUILD that economic base has led to some conflict in the last few years. Publicly, there is broad support for the their success. People and officials in the cities that border tribal lands who criticize the tribes ask to do so off the record for fear of upsetting tribal members. As one person in Pendleton said, “They’re very powerful.”

|

Critics say tribes have an unfair competitive advantage: They don’t pay property taxes. They’re exempt from state land-use laws. They don’t pay state taxes on the profits from their casinos. How can non-tribal businesses be expected to compete with that?

“The people who don’t understand what the [Umatilla’s] 1855 treaty means are the people who don’t get it,” Mills, the OECDD business development officer, says. “You have to understand that by law this is what they are able to do.”

Oregon’s tribes signed treaties with the federal government at different times during the 1880s. Their sovereignty — even though it wasn’t honored for more than 100 years — gave them the rights that currently draw complaints. Tribal governments, like state and local governments and nonprofits, don’t pay taxes — just like one state does not pay taxes to another state. However, tribal businesses that aren’t on land that’s been placed in federal trust do pay taxes, as do their employees.

As multi-million dollar projects spring up in economically depressed areas, it’s not surprising that some jealous residents might begin imagining what individual tribes are worth. But thinking they’re flush with cash is the wrong assumption to make, says Robert Whelan, one of the economists who did the ECONorthwest study on gaming. Oregon tribes had to borrow a lot of money to build their casinos, often at high rates because of their lack of financial assets, he says. Now that money is coming in, he says, much of it goes to government administration and providing health, education and housing services to their members. That can be a heavy load for a tribe like the Grand Ronde, with almost 5,000 members.

“We’re still at the early stages of what it will ultimately look like for the tribes,” Whelan says. “They’re still at the early stages of gaming, developing businesses and providing social benefits to tribal members. They’re starting to see changes in the unemployment rate, in health care and education, but they’re still far behind people who are not tribal members.”

It’s that commitment to their culture and their members that makes Oregon’s tribes a unique economic entity. As Umatilla chairman Minthorn says, “I view it as your culture and your economy are one and the same thing.”

THE FUTURE OF GAMING as it stands today is uncertain. Oregon tribes with the smallest, most remotely situated casinos — the Klamath, Burns Paiute and Warm Springs — have made controversial overtures about starting off-reservation casinos closer to metropolitan areas. Obviously that would cut into the profits of other tribes.

And so the future lies in further diversification, which the tribes readily acknowledge. Who’s doing the best at that? When Tom Hampson, executive director of the Oregon Native American Business Enterprise Network, talks about the tribes who’ve done the best at diversifying, the names at the top of his list aren’t surprising: the Coquille (“very thoughtful in how they’re doing what they’re doing”); the Cow Creek (“could have stuck to tourism but they really stepped outside of that”); the Umatilla (“great continuity of leadership; they’re on a bit of a streak”).

The Umatilla plan to keep that streak going: A marketing push to find more high tech and light manufacturing for their business park will be ready in the next six months, says Bill Tovey, director of the tribe’s department of economic and community development. Then there are expansions to Wildhorse Resort: more space for recreational vehicles, another dining facility. “You can’t rule anything out for the future,” Tovey says.

Other tribes are racing ahead as well. The Cow Creek have a new sewer treatment facility in the works, plus a massive expansion to the hotel portion of their resort, which will break ground this year. The Grand Ronde and Siletz have their development in Keizer. The Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw are waiting for the passage of a bill — introduced by Sen. Gordon Smith, R-Ore. — that would give them the Cape Arago Lighthouse and nearby land.

Unsurprisingly, that future is rooted in the past. Minthorn says his tribe’s economic drive is evidenced by trading that stretched all the way to Mexico before the arrival of European settlers. They hit a rough spot in the early 1970s when a faction of the tribe successfully fought to divide up among members a $2 million federal payment, instead of investing in a hotel and golf course on I-84. It’s been a slow process to relearn the importance of economic diversity, Minthorn says. But by the time casinos came to Oregon, he says tribal members understood that need.

“A lot of damage was done to our homeland, a lot of promises were broken. There’s something called justice, but you have to do something to achieve that. You have to work to make this growth happen,” Minthorn says, then finishes with a laugh: “It’s the American way, isn’t it?”

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]

Buildings for the first two tenants in the Umatilla’s

Buildings for the first two tenants in the Umatilla’s