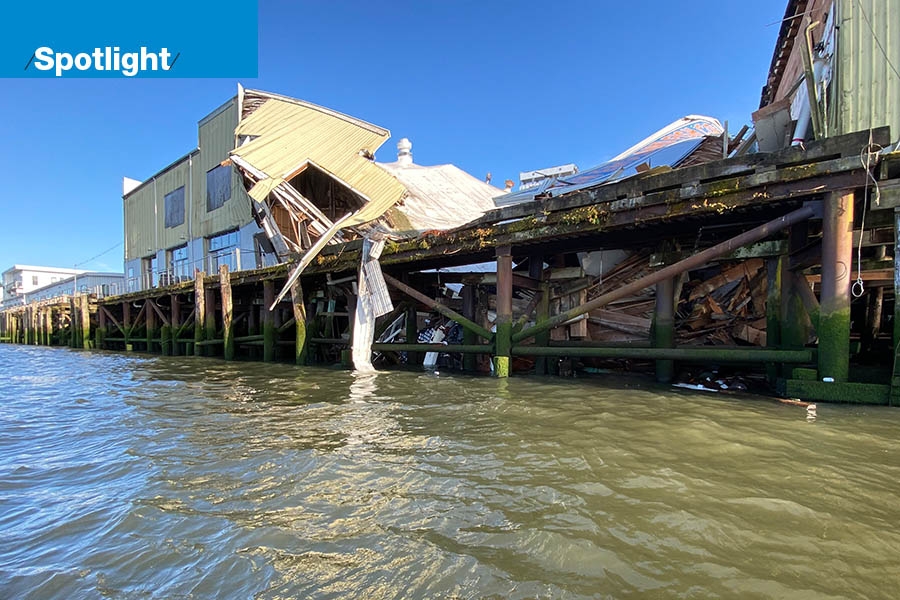

The Buoy Beer Company building partially collapsed this summer. A structural engineer says he predicted the implosion 19 years ago.

In mid-September Astoria’s Buoy Beer Company announced plans to stabilize the south wall of its brewery on the city’s waterfront, which would allow the city to reopen the fenced-off Astoria Riverwalk.

The city issued a permit for the job Sept. 12 — almost exactly three months after the brewery’s original building imploded, sending beer cans, labels and other debris tumbling into the Columbia River.

The brewery had operated on a dock in Astoria — the oldest white settlement west of the Rockies — since 2014. Its beers garnered immediate praise in the brewing world, and the brewery and restaurant, housed in a former fish-processing plant, was hailed as a fun, family-friendly gathering spot. Its opening, and that of the Fort George Brewery in 2007, also marked a shift in the city’s identity — from a down-on-its-luck former fishing town to a place where locals and tourists alike could enjoy draft beer, fish and chips, and a great view just upstream of the place where the river meets the ocean. Contractor Jared Rickenbach even carved out a section of rotted floor and installed a window for watching sea lions.

In the weeks that followed the collapse, the brewery announced that it was reopening in a new location and offered free tasting flights at Pilot House Distilling (which the brewery owns) to those who helped clean up debris from the implosion.

No one was injured in the collapse, likely because the kitchen had been closed since September 2021, due, the company said, to problems with the pilings that supported the dock. When the building imploded, a spokesperson for Buoy told The Astorian, “The structural issue was known.”

That raises the question: Who knew and for how long?

Documents reviewed by Oregon Business suggest personnel at Bornstein Seafoods — which owns the building and whose co-owner, Andrew Bornstein, is also a founder and secretary at River Barrel Brewing, Buoy’s parent company — knew as long ago as 2003 that the pilings that support the building were in a dangerous state of disrepair.

It’s not clear what, if anything, has been done to address the problem. It’s also unclear whether the building was evaluated by a structural engineer before it opened as a brewery, which is required under the state building code.

OB reviewed hundreds of documents from city, county and state agencies detailing the history of the building since the brewery’s incorporation. The records include numerous building permits and permit applications for remodeling work, but as of this writing, OB had not located any permits for work on the dock or pilings.

That doesn’t necessarily mean those records don’t exist, or that no work was done. As of this writing, a public-record request with the Army Corps of Engineers was still outstanding.

And because of the location of the brewery and the nature of the building, multiple government agencies have jurisdiction to receive and issue building permits. In Astoria, the city issues building permits for the structure itself, and Clatsop County issues permits for electrical work. The Department of State Lands owns the land adjacent to the waterway and can issue permits for fill work, including work on pile fields. The Army Corps of Engineers has regulatory authority over waterways themselves and sometimes issues permits for maritime construction.

“In order to get an Army Corps of Engineers permit, imagine a ladder, and the ladder has seven departments that you have to cross off if you [want to] check off that ladder. Before you get their approval, you’ve got to satisfy every jurisdiction in the way,” structural engineer Bill Marczewski says. “The city has to sign off on the things that you’re doing, the county, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, NOAA, National Marine Fisheries and the DEQ.”

It’s a tedious process many contractors simply skip, he says. And the system isn’t set up to make sure they go through the appropriate process.

Marczewski has operated his own structural engineering firm, BSM Engineering in Portland, since 2017, but prior to that he ran BSM Consulting Engineers in Astoria from 2005 to 2016, state records show.

Prior to that, he worked for another engineering firm in Astoria. In that capacity, in 2003, Marczewski inspected the property that until June housed Buoy. At that time, the building had housed Bornstein Seafoods since 1982 and would until 2007, when the fish-processing plant moved to the Port of Astoria. He tells OB he was contacted by Bergerson Construction, a maritime construction company in Astoria that does pile repair, which was hired by Bornstein, but he isn’t sure what precisely prompted the inspection — only that there was no pending change-of-use or change-of-occupancy application.

Marczewski says he observed axial loads “in the initial stages of buckling”; lateral spreading of the north and south walls; and piles that were not braced adequately.

“This facility is in extremely poor condition and the life-safety of all occupants is at risk,” Marczewski wrote in a letter dated Oct. 16, 2003, and reviewed by OB. “The building is in the initial stages of partial, if not complete, failure. We have little doubt collapse is inevitable.”

Before sending the letter, he says, he called the city’s building official, who told him the company didn’t need to make any changes to the structure unless there was a change of use or change of occupancy. (That official is no longer employed by the city, which has gone through at least five or six building officials in the past 20 years, interim city manager Paul Benoit says.)

In addition to concerns about the pilings —which he says are held to the pile field under the Astoria Riverfront Trolley tracks by a horizontal tether — Marczewski says there were significant issues with the building itself. The floors were uneven, and both the second and first floor were covered with 4 to 6 inches of concrete, placing too much pressure on the foundation.

The letter closes with several recommendations, including a recommendation to place a steel perimeter around the dock to keep it from drifting.

After Marczewski sent his letter, he says Bornstein asked him to make his report “more black and white,” and also engaged a second engineering firm, Conlee Engineers, to inspect the building. Marczewski says he was invited along to that second inspection but felt he was being pressured to soften his report and declined.

Marczewski’s letter was sent directly to Bornstein, with copies to Bergerson and Julius Horvath, a Vancouver, Wash.-based engineer who accompanied him on the inspection.

Another document suggests the property owners and a principal in the brewing company have been aware of the need to repair the pile field since 2007.

In 2007 Bornstein Seafoods, in conjunction with a company called Greenlite Development, submitted a joint permit application to the DSL and the Army Corps of Engineers to redevelop the property as a multiuse condominium and retail facility.

“To accomplish this project, the entire building and platform that currently exist on this submerged-land lease portion of Bornstein’s property will need to be removed so that a thorough analysis of the current piling field can be performed by certified engineers,” the application says. “While performing maintenance and repair to the current piling field, new pilings may need to be driven to replace current pilings in order to increase the structural integrity of the field. While the extent of necessary new piles cannot be determined at this time, it appears that a great deal of pilings currently exist within our field, and that these may be in excess of the future requirement.”

State records show Greenlite was incorporated in 2009, with Andrew Bornstein listed as registered agent; the company dissolved in 2012. Jay Bornstein, then the president of Bornstein Seafoods — an 88-year-old company with facilities in Newport, Warrenton, Astoria and Bellingham, Wash. — is the primary applicant on the 2007 paperwork; he has since sold the company to Andrew and his two other sons.

There’s no record of a permit being issued for any part of that project. Instead, the Bornstein building sat vacant until 2013, when Buoy co-founder Luke Colvin and Rickenbach Construction applied for a conditional-use permit with the City of Astoria.

The file that includes that permit application bears the city’s stamp of approval. What it doesn’t include, however, is a copy of a structural evaluation by an engineer.

“That’s not something that we would require. If it’s not new construction, that’s not required,” says Paul Benoit, who took over as interim city manager of Astoria in July but served as the city’s community development director from 1986 to 2003 and as city manager from 2005 to 2013.

Chapter 34 of the state building code, which specifically addresses existing buildings, says: “The owner shall have a structural analysis of the existing building made to determine adequacy of structural systems for the proposed alteration, addition or change of occupancy.” The code also includes a clause saying alterations to historic buildings may be made without conforming to all aspects of code, provided any unsafe conditions are corrected, and the restored building will be “no more hazardous based on life safety, fire safety and sanitation” than the existing building.

The state’s Reference Manual for Building Officials also says structural evaluations must be practiced by licensed engineers. No engineer is named in the 2013 conditional-use application.

Rickenbach Construction — which has performed the bulk of remodel work on the building, including the project to stabilize the city wall — declined an initial request for an interview, and did not reply to an email specifically asking whether an engineer was engaged to perform a structural assessment when the building underwent a change of use.

In September OB sent an email to Andrew Bornstein, Luke Colvin and Buoy president David Kroening that included questions about the 2003 inspection, the 2007 permit, and what work — if any — has been done on the pile field since the business incorporated and since the 2021 kitchen closure.

“We have no comment at this time,” Kroening wrote.

Benoit says it’s possible some pile repairs were performed under the building, which is about 100 years old and housed a feed-and-grain facility, another seafood processor and a mink-feed storage site before Bornstein moved in.

“What happens over 100 years is they’ll cut off the section of piling that is rotten. They’ll cut it off and put a new post in. They don’t have to go to the Corps of Engineers for that,” Benoit says.

Historian John Goodenberger says that in the early 20th century, when there were 24 canneries active on Astoria’s waterfront, there were pile bucks “almost 24/7 working on pilings.” Benoit says most of the waterfront property owners still retain facilities workers to work on pilings.

Marczewski says major piling repair is time-consuming and expensive, and there are waterfront buildings all over the West Coast with significant structural challenges. Since the 2003 inspection, he’s avoided the building and told family and friends to stay away as well.

Officially, however, the cause of the collapse is still unknown.

“I don’t know that anybody other than Buoy knows,” Benoit says.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.