Danielle Elsener’s work to promote zero-waste fashion is gaining the attention of apparel makers, potentially revolutionizing one of the most wasteful and polluting sectors in existence.

Portland-based fashion designer Danielle Elsener was in her final year of a master’s degree at the Royal College of Art in London when the coronavirus pandemic put the city into lockdown in the spring of 2020. Stuck at home with nowhere to go, she put her apparel-making skills to work by designing scrubs for the U.K.’s National Health Service.

Danielle Elsener wearing her NHS scrubs. Courtesy of Danielle Elsener

Danielle Elsener wearing her NHS scrubs. Courtesy of Danielle Elsener

Her patterns had a twist. They were designed to create no waste — an approach that has formed the basis of her work as a zero-waste systems designer. She made the patterns available online for anyone to download.

“It was on a few sheets of A4 paper that you could print off. It was completely open source. I said, ‘There are probably mistakes, just tell me and I will fix it.’”

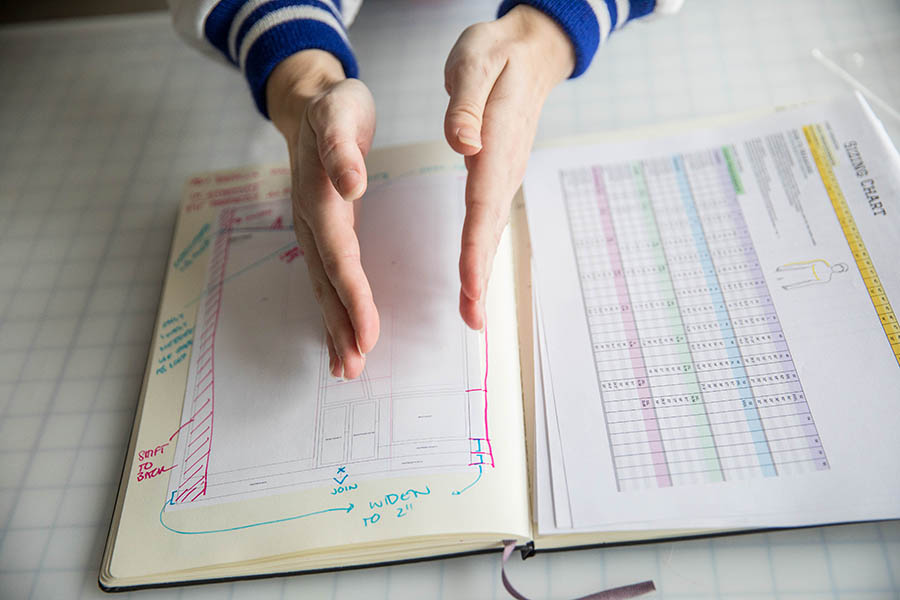

Danielle Elsener’s open-source pattern for scrubs. Courtesy of Danielle Elsener

Danielle Elsener’s open-source pattern for scrubs. Courtesy of Danielle Elsener

The response was overwhelming. People contacted her over social media to share their thoughts and make suggestions for improvements. One sewist in the U.K. became so invested that she asked if she could make video tutorials on how to construct zero-waste garments. A factory in Myanmar contacted her to ask if they could make full runs from the design.

“It really pivoted how I work,” says Elsener. “A lot of my work has been about including people and making zero-waste design more accessible and interesting.”

Her design ideas are now influencing global heavyweights in clothes manufacturing and prompting businesses to rethink the way they design clothes to meet sustainability goals. It is an important step in improving the environmental performance of the garment industry, which has a terrible record of waste and pollution.

Elsener had a gift for clothes design and sewing at a young age. It all started at the age of 8, when her parents gave her a Christmas gift card to the sewing store in her neighborhood. She soon learned how to make a skirt. From there she started accompanying her aunt to a sewing and quilting retreat, where she wowed the more mature attendees with her sewing skills.

“I went to this retreat as a young kid, and I was the little one running around quilting with 60-year-old ladies. They were always marveling at me because I always finished first,” says Elsener.

Her interests in cutting down waste were borne out of a tendency toward impatience. “I never wanted to wait for my mom to take me to the fabric store, so I just used whatever was around me. I would make patterns out of newspapers, use recycled bags to make things. I always wanted to make stuff, and if there wasn’t anything around, I would find a way to do it.”

She also credits her grandmother’s frugal ways as an early influence on her. “My mom says my grandmother was a true zero-waste warrior before anyone else was doing it and before it was a trend.”

Her ideas of creating garments that produce no waste in the design stage matured when she attended Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) to study fashion. In her third year, she stumbled across some pioneering pattern makers, which led her to the work of Holly McQuillan and Timo Rissanen, the pioneers of zero-waste fashion.

The designers co-authored a book, Zero Waste Fashion Design, which promotes sustainable fashion systems and practice. “Something about their work struck a chord with me,” says Elsener. “It brought me into this rabbit hole that I haven’t been able to escape.”

Figuring out how to design garments without producing any waste is a skill akin to working out a math puzzle. “Having something to solve outside of a normal fashion problem and having constraints to design to are something I really enjoy,” she says.

Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

The fashion industry has a long way to go toward adopting sustainable manufacturing practices. The rise of fast fashion — the design and manufacture of large volumes of cheap clothes that are designed to be discarded quickly — means the sector is creating more waste than ever before.

On average, people bought 60% more clothes in 2014 than in 2000. The industry is the second-largest industrial consumer of water and produces 10% of the world’s greenhouse gases.

An average of 15% of fabric is wasted at the cutting stage, according to Fashion Revolution, a nonprofit advocacy group. That percentage goes up to around 40% for luxury items. This leads to 60 billion square meters of fabric turning into waste annually.

Only a small proportion of this waste, 10%, is recycled. An estimated 57% of wasted fabric goes to the landfill and 24% is incinerated. Cutting down fabric waste is critical to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the industry; 80% of the carbon-dioxide emissions come from fabric production.

Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Elsener designed a zero-waste clothing collection while at SCAD, and she has made this approach the basis of her work since. After graduating, she worked at several large apparel makers, including Ralph Lauren, Reebok, Urban Outfitters and Nike. At each employer, she proposed a zero-waste collection. But it was hard for her ideas to gain traction at first.

The idea of zero-waste fashion design “wasn’t at the front of everyone’s minds,” says Elsener. “If you have a system that is already working and you know what your customers like, it can be really difficult to switch paths.”

Elsener moved to Portland in 2015 to work for Nike in basketball apparel design. While at Nike, she prototyped a zero-waste methodology. As an independent, zero-waste systems designer, she recently held a workshop at the sportswear maker, where she taught the design team about zero-waste history and applications.

Nike says on its website that it is focused on eliminating waste “by creating products that are better for athletes and our planet.” A Nike spokesperson said in an email: “As part of NIKE, Inc.’s 2025 targets, we will recycle, refurbish or donate 10x the amount of post-consumer waste collected.” The company also aims to divert 100% of waste from the landfill in its extended supply chain.

Elsener left Nike in 2018 to pursue a master’s degree at the Royal College of Art. The move proved life-changing as it set her on a path toward independence as a zero-waste designer.

While at the Royal College of Art, she applied for a grant from the Evian Activate Movement initiative, a new program that awards €50,000 grants for “sustainability-focused design and innovation projects.” Shweta Harit, Evian global brand vice president, said in an email that the initiative is designed to “champion a tidal wave of new thinkers and innovators with sustainability built into their core ethos; we feel that Danielle embodies all that we continue to champion as a brand.”

Winning that competition has enabled Elsener, who moved back to Portland in 2020, to develop a three-pronged plan for launching a zero-waste design business under the moniker DECODE.

A large part of her work is building an online platform with other designers that provides tools for people to pursue zero-waste design. The website has a pattern master, which contains information and instructions for designing zero-waste garments. She also holds workshops and events to teach and educate people about zero-waste design.

Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Her ideas are gaining traction among apparel makers, particularly in the sportswear sector. Nike is “way ahead of their peers” in zero-waste design, says Elsener. “The athletic industry is a lot more tuned in to what people want because they are serving the needs of athletes. If the athlete or consumer wants more sustainable clothing, then that is where they go.”

Elsener has also worked with local, smaller apparel makers to incorporate zero waste into their collections. For the past few months, she has worked with Settlemier’s Awards Jackets, a Portland maker of varsity-style jackets and logos. She is working with the third-generation-owned factory to digitize its patterns and ultimately create zero-waste versions.

Aaron Settlemier, the 39-year-old owner, says the company was seeking to revamp its decades-old, worn paper jacket patterns when it came across Elsener’s work. “We saw a whole new way of thinking about updating patterns; it went from a technical change to a philosophical change,” says Settlemier, who took over the business from his mother.

The company, which makes all its jackets at its 8,000-square-foot Portland factory, wastes about 20% of fabric through its paper patterns. The chance to reduce waste fits in with Settlemier’s way of thinking. “My mom always said, ‘When you solve the problem of waste, you will change the company for the better.’ She meant that as an economic driver, but for my generation, it is more about the impact on the planet.”

Elsener is also designing her own clothes collection to sell to retailers. Her specialty is menswear, but she describes the pieces as nongendered. The garments are also designed to look as “normal” as possible.

“It is my goal to create pieces that do not necessarily look like they are zero waste, because that often comes with the connotation of eco-chic or big beige sacks. I am trying to create normal garments that people would wear but that have something of interest, like a pattern that is cut in one place but reappears in another, so you understand there is something more going on.”

Ultimately, Elsener wants to launch a micro zero-waste factory to produce garments in the U.S. Part of her proposal for the Evian Activate Movement grant was to create a mobile micro factory in a shipping container, which would come with machinery, tools and resources to create zero-waste garments.

The coronavirus pandemic has put her plan of developing a micro factory on hold, since “with COVID, it didn’t make sense to make a physical space.” But she wants to realize that plan eventually. Despite most garment-making taking place overseas, she wants to keep the factory in the U.S.

“Personally, I like to have [the manufacturing] close by so I can see what is going on. When I was trying to get some garments produced in the past, it was really difficult working through such a long communication chain. The way you construct zero-waste design is different. If you can’t physically talk to the person or there is a language barrier, it is difficult to communicate what actually needs to happen,” she says. “In the States, I like being able to ensure the standards of what you are producing and making sure people have living wages.”

The international supply-chain disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic will likely accelerate the trend of onshoring manufacturing back to the U.S., which would boost Elsener’s zero-waste factory plans. Ultimately, she wants to bring zero-waste fashion to as many people as possible.

And the apparel makers she is working with also hope to influence others to follow the zero-waste path. “We definitely want other factories to see what we are doing and get inspired,” says Settlemier.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.