Cities across Oregon transform industrial waterfront sites into recreation opportunities.

In today’s urban development landscape, it’s all about the river. As waterways become less critical for industry and cities face pressure to attract and retain workers, it seems nearly every Oregon town, large and small, is undertaking a riverfront redesign.

Waterfront redevelopment came into fashion during the post-industrial era in the 1960s. During this time, a task force appointed by Governor Tom McCall knocked out Portland’s Harbor Drive Freeway in favor of the now iconic Tom McCall Waterfront Park. The development followed the principles of the Olmsted Brothers 1903 park plan, prioritizing people walking over driving and other uses.

As urban populations multiply, public waterfront amenities are becoming essential. Residents packed into denser developments, landscape architect Gina Ford argues, increasingly see waterfront parks as “one giant shared front yard.”

On September 29, Vancouver opened portions of a $31 million, 7.3-acre park. Hugging the Columbia River, the park will include a meandering path, a playground, an urban beach and a fountain evoking the Columbia River watershed.

The City of Eugene approved a design this fall for a riverfront development on the 16-acre former headquarters of the Eugene Water and Electric Board. The latest estimates for the project total $12.2 million. The plan features a riverfront plaza surrounded by a restaurant, a hotel, 70 townhomes and 215 market-rate and affordable apartments. The development will connect to a planned three-acre riverfront park.

A map of the new Vancouver Waterfront Park. City of Vancouver

A map of the new Vancouver Waterfront Park. City of Vancouver

The rural community of John Day is transforming a former mill site along the John Day River into an “innovation gateway” with opportunities for both recreation and education. At a price tag of around $20 million, the plan encompasses hydroponic greenhouses, botanical gardens, an academic campus for agricultural research, and a multi-use riverfront trail. It’s a prime example of modern-day park planning that provides educational and recreation activities, rather than passive open spaces.

The $10 million Peter Courtney Minto Island Bridge, opened last year, links Salem’s up-and-coming downtown with 1,300 acres of parkland, an area larger than New York’s Central Park. Funding comes from federal, state, and local sources including Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, Business Oregon and the Department of Transportation.

Since it developed its waterfront urban renewal plan in 2008, Hood River continues to expand riverside amenities. The empty industrial lots at the confluence of the Columbia and Hood Rivers are rising again as craft breweries and luxury apartments. The Hood River Riverfront Park, completed in 2013, replaced a light industrial site.

The view from a proposed viewing platform in the Willamette Falls redevelopment plan.

Not all of these projects are success stories. Mounting costs toppled the ambitious plans for developing a vibrant waterfront neighborhood on the 33-acre Zidell Yards site on Portland’s south waterfront.

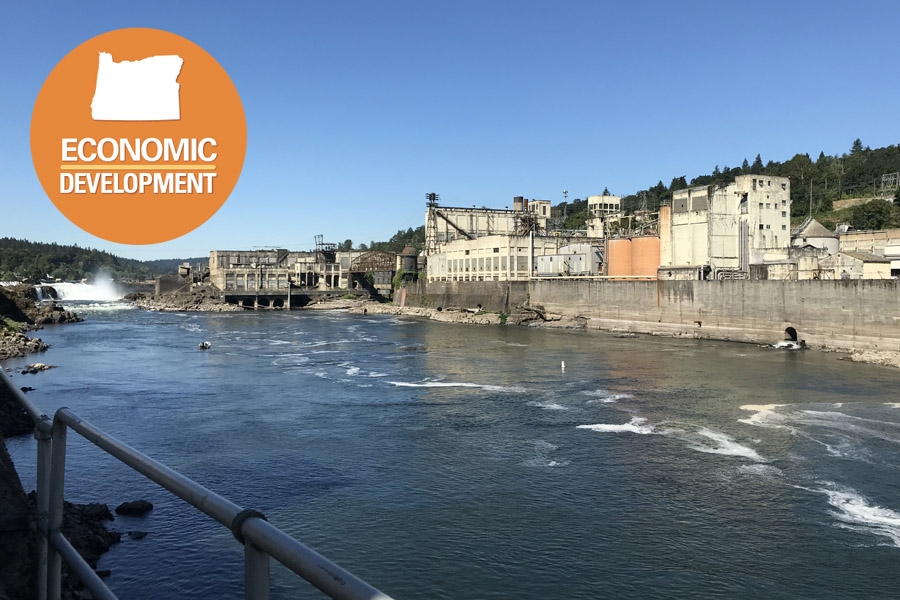

The proposed Willamette Falls redevelopment in Oregon City has also faced hurdles. The design features a riverwalk that weaves through the site’s industrial past and culminates with a view of the second largest waterfall by volume in North America. Public partners are haggling with the landowner over the project’s cost and design.

These projects illustrate the perils of public-private partnerships. But that won’t stop riverfront revitalization, as the river becomes one of the most important economic development tools for the 21st century city.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.