The chief investment officer of the Oregon State Treasury talks about the complexity of investing post-financial crisis, why solving the $22 billion unfunded liability is not his concern and the poor quality of financial news reporting.

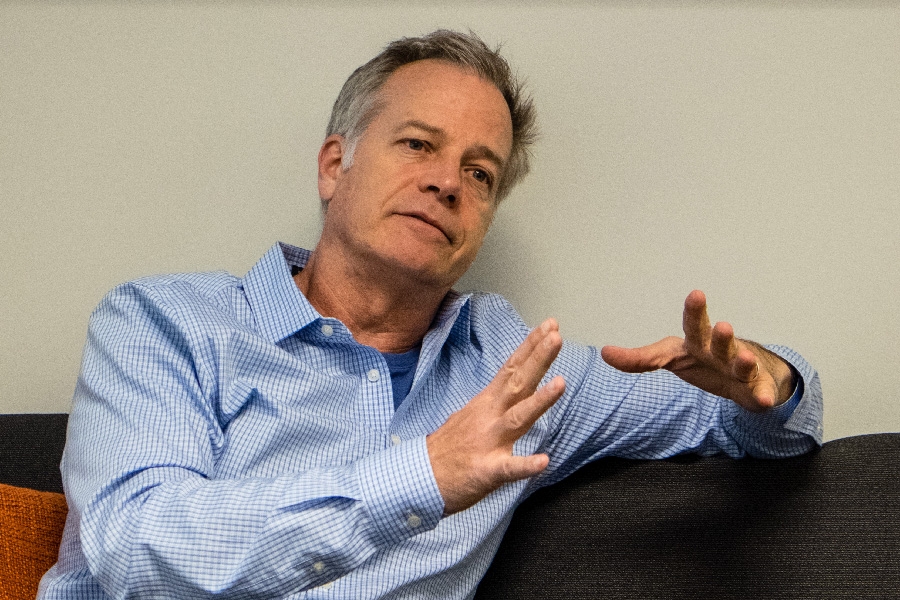

The week before the New York Times put Oregon’s pension woes in the national spotlight, we sat down with John Skjervem, the man who is responsible for managing $106 billion in public funds. Most of that money comprises Oregon’s public employees retirement fund, the investment vehicle for the Public Employees Retirement System (PERS).

Skjervem joined the Oregon State Treasury in 2012 after spending more than 20 years at wealth management firm Northern Trust. In our conversation, the CIO didn’t pull any punches, mixing complex financial analysis with frank talk about PERS and not-so-veiled barbs at the financial press and mutual fund sales tactics.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You are responsible for managing Oregon’s $78 billion public employees retirement fund. What keeps you up most at night about that responsibility?

I would say assimilating a whole generation of new people. We were a notoriously lean staff for many years. It was a source of great and deserved pride to manage a successful investment organization as lean as we did for many years. But the pension fund portfolio finally got very large and very complex with investments in assets all over the world and in all types of public and private market strategies. Early in my tenure and in conversations with Ted Wheeler (former state treasurer) I said we need more resources, primarily because of the complexity. That began a series of campaigns in regular and short sessions to bring more resources into the division.

What is your expansion plan for the fund in terms of resources and staff?

We have doubled the staff. I was astounded when I got here that the division was able to do what it was doing with so few people. That is a testament to the quality of the people, the dedication of the people.

Photo credit: Jason Kaplan

Photo credit: Jason Kaplan

What is your solution to bridging the retirement fund’s $22 billion unfunded liabilities gap?

It is not an issue for us. The liability is a reflection of the benefits that were promised. It doesn’t affect the way we manage the money. We remind people that on the investment side we are returns takers not returns makers. We go out into the markets every day and compete, but the markets give a certain level of return, what investment people call beta. We cannot create beta out of thin air. Returns makers are people in policy positions. They ultimately determine through fiscal and monetary policy what the level of beta returns will be. In those areas of the portfolio where we think we have a competitive advantage we add alpha. There is no investment strategy to solve the unfunded liability.

SEE RELATED STORY: OPINION: SOARING PERS COSTS REQUIRE ACTIVE DEBT MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

You outsource most investing to external investment managers. To what extent would you like to bring more investment management in-house?

We have already insourced many of the investment activities. The important thing about insourcing goes back to skill. The competitive advantage we have in Tigard, Oregon, is a cost advantage; it is not a skill advantage. We are a public plan — anybody that has genuine skill and can show that in the form of alpha isn’t going to work for me because I can’t pay them what they are worth.

We have to be clear-eyed about our advantages: Oregon is a terrific place to live; we have a terrific brand as an institutional investor. That will accrue in what I call plain vanilla mandates – long-only fixed income; high-quality, long-only public equity; large cap – those are investments in asset classes for which the application of skill is not sufficiently rewarded. Therefore, that is the perfect candidate for us.

How concerned are you that investment fees are a drag on the fund?

The investment fees are a drag on the fund. It is the business we are in. Skill-based strategies cost money in the form of fees. Skills are sufficiently rewarded in certain alternative asset classes, like private real estate, private equity, minerals, mining, timber, agriculture. Those are important exposures for us to have because they make the portfolio more resilient over time in the form of diversification. One of our most important jobs is to scrutinize the managers in those strategies to make sure we are being rewarded for the fees we pay. That is easy to do in public markets. It is much harder to do in private markets. But is one of the top responsibilities of the staff.

What is the part of the job you most enjoy?

We have an almost exclusive objective of securing the financial future of public employee retirees. We are the largest institutional investor in one of the most premier venture capital funds (he declined to name the fund).

You and I could win the lottery tomorrow and we would never get access to that fund because we were not there in the beginning; we are not networked in. And yet Oregon, because of its brand and its connections developed over 37 years, has access. That may sound trite, but contrast that to my role in a commercial setting and you don’t always have that alignment with fiduciary ‘true north.’ You have all sorts of competing priorities like quarterly earnings targets or market share or marketing campaigns or client service and all the other elements that come with a commercial appointment.

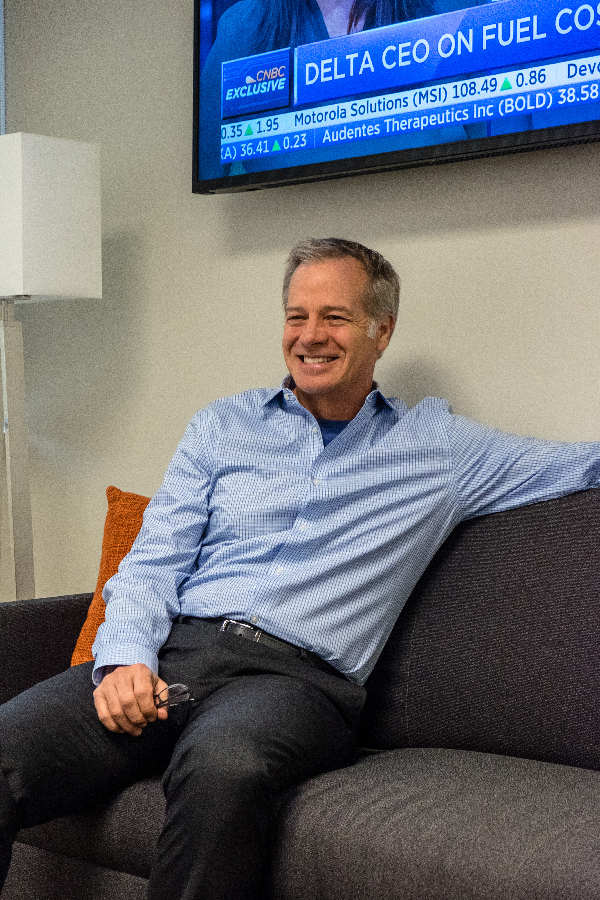

I don’t have to sell anything to anybody. I don’t have to keep clients happy. I don’t have to go on CNBC like I used to in order to try to promote a commercial brand.

Photo credit: Jason Kaplan

Photo credit: Jason Kaplan

What is your most memorable news story to come out of the financial investing world?

I am pretty cynical about financial reporting. It has gotten much worse. With the explosion of bandwidth and content you have more information than ever. But I don’t think it is information; it is opinion and commentary. And then you have marketing experts that package that so that the guy in the street thinks it is news and that they are building knowledge from this information. And they are not. It is white noise. The only way to be successful, especially building an institutional investment portfolio, is thinking long term. This is one of our few remaining competitive advantages. We work for an organization for which the investment horizon is truly measured in decades.

What is the most important lesson you learned from the 2008 financial crisis?

A common refrain after the crisis was diversification didn’t work. That is not true. Diversification worked just as it was designed. The lesson learned was that many institutional investors were not diversified. Equity risk had seeped into all the other parts of the portfolio. When equity assets went down all the asset classes went down – not because diversification didn’t work – because they really weren’t diversified. That is why it is so important to remain disciplined.

How have you increased diversification in Oregon’s public pension fund?

We created an alternatives portfolio for the express purpose of being a truly diversifying asset. It is a portfolio that includes timber and agriculture, infrastructure and minerals and mining – exposures and strategies that aren’t uncorrelated – that would be the holy grail – but hopefully less than perfectly correlated. We can’t time markets so you build the most diversifying portfolio you can.

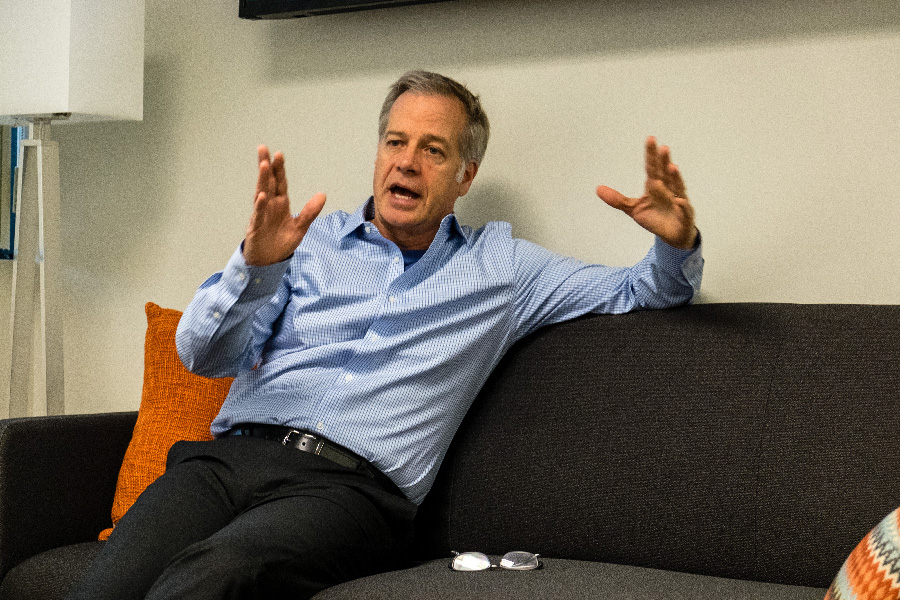

Who do you most respect in the financial investing world?

I respect our own program and the folks that served in governance roles 37 years ago, namely Jim George and Roger Meier, who made the first substantive institutional investment in private equity.

It is the greatest, seldom-told story told in Oregon. Private equity today is a $2 trillion industry. It has created more billionaires than any other industry in a long time. In 1981, we announced the deal with this unheard of little boutique out of New York called KKR. We announced a transaction that nobody had heard of called a leveraged buyout. That transaction was consummated in 1982; it was $178 million – $150 was debt, $28 million was equity.

That was off the charts in terms of size. Private equity before then had been high net worth individuals and $25 million investments from insurance companies. When you think of the courage it took to partner with a boutique out of New York nobody had heard of, put 8% of the fund in an investment strategy that nobody had heard of. The only thing people had heard of was that it was a leveraged buyout of Fred Meyer, so there was familiarity with the asset, but not with the players or the financing technique. It is what built our brand.

Photo credit: Jason Kaplan

Photo credit: Jason Kaplan

What will be the biggest transformation in the retirement plan sector over the next decade?

I suspect it will be a big acceleration of programs like OregonSaves where we realize the retirement systems of the past are insufficient in size for reasons both political and social. We need to create new structures and programs like OregonSaves so that people can start taking a bigger share of retirement savings responsibility.