Before this summer, the penalty for distributing fentanyl testing strips — which can help people determine whether other drugs are contaminated with it — was higher than the penalty for carrying most illegal drugs. A new law does away with that discrepancy.

Josh Davis has worked in nightlife most of his adult life.

Davis, 49, opened Star Bar in Southeast Portland in 2010, having previously owned a bar in Seattle and having worked as a bar manager and bartender for years before that.

It’s fair to say drug use is common in the industry, both for bar staff who may use stimulants to get through long shifts and for patrons — and Davis has seen the human cost firsthand.

“In the ’90s, growing up in Seattle, I had a lot of friends overdose from heroin, and that was not something that I would like anybody else to go through,” the soft-spoken Davis tells Oregon Business. In recent years, the increase in fentanyl use — and attendant overdoses — became impossible for him to ignore.

“The fentanyl deaths started to mount, and then it was suddenly introduced into cocaine, then people kind of on the periphery of this bar started to overdose, and we’d hear about it,” Davis says.

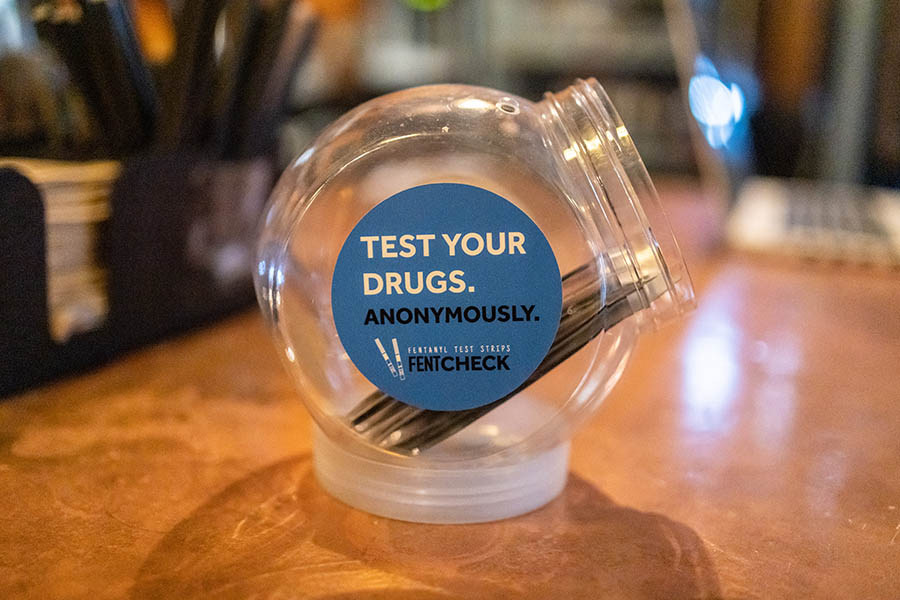

Davis says he heard about FentCheck — a nonprofit that makes and distributes fentanyl testing strips — through a friend who owns a retail store. He got in touch with the organization’s co-founder, Dean Shold, and started making the test strips available at the bar. They’re in a fish bowl on the bar counter, where customers can easily grab them without having to ask questions.

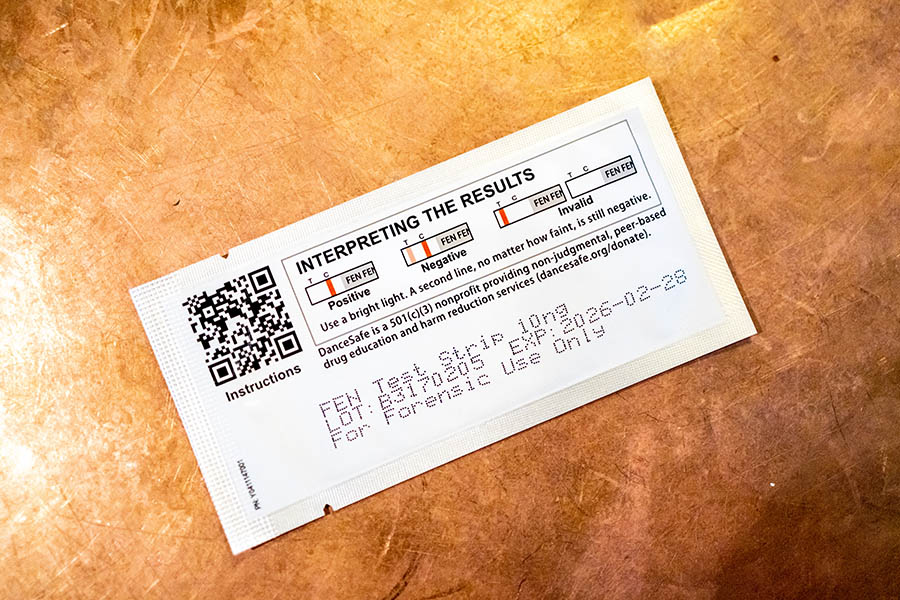

As recently as last month, distributing such strips was illegal in Oregon. An Oregon law modeled on federal legislation from the 1970s classifies testing equipment as drug paraphernalia and issues a fine between $2,000 and $10,000 for possessing items in that category. Under Measure 110, which Oregon voters passed in 2020, possession of most controlled substances is a Class E civil violation punishable with a $100 fine. (The Legislature rolled back part of 110 this session, making it a misdemeanor to possess “a mixture or substance containing a detectable amount of fentanyl” or five “user units” — that is, pills — of a drug that contains a detectable amount of fentanyl.)

The Legislature also passed House Bill 2395, which redefines “drug paraphernalia” to exclude single-use drug test strips, hypodermic needles or “any other item designed to prevent or reduce the potential harm associated with the use of controlled substances” — thus doing away with the prior penalty. As this issue went to press, the bill was on its way to Gov. Tina Kotek’s desk; it will be effective as soon as it’s signed into law.

The bill also makes it legal for a law enforcement officer, firefighters and emergency medical services providers to distribute and administer naloxone, an opioid agonist that can reverse overdose.

“This acute, sudden overdose increase has really been traumatic and really concerning as a frontline physician taking care of people who overdose,” says Maxine Dexter (D-Portland), who is also a pulmonologist and critical-care physician. “This all came about because I have rushed in as a critical-care doctor to rooms where patients stopped breathing: They have had a cardiopulmonary arrest, meaning their heart has stopped or they’re no longer breathing. The first thing that I do is give naloxone, because no matter who it is, it’s safe. It quickly revives people if they are suffering from an overdose. It’s just part of our urgent response to an arrest, and I know it’s safe. I know that it is effective. And we need it everywhere in our community to make sure people are, you know, kept alive long enough to get into recovery, if at all possible.”

House Bill 2395 passed out of the House of Representatives in early March. But for much of the spring its fate was uncertain, due to a six-week walkout by Republican senators that left the Legislature without the quorum required under the state’s Constitution to pass new laws.

That hamstrung legislative business until mid-June, leaving observers concerned that testing strips would remain in a legal gray area until the next session. But an amended version of the bill passed out of both chambers June 24, the day before the Legislature adjourned.

“Oregonian lives will be saved through this bill,” Shold says. He is originally from Portland and recently moved back but had previously worked as chief technology officer at Alameda Health System, a public health care system in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is sometimes prescribed for patients in extreme pain — such as patients recovering from surgery or for advanced-stage cancer patients — but that’s also manufactured and sold by black-market dealers. The Centers for Disease Control describe the drug as 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine. It’s also lethal in smaller amounts than other drugs: Shold says just 2 milligrams can be a lethal dose.

He says in his previous role, he started researching the opioid epidemic and learned that one of the contributing factors is an increase in other illegal drugs — like cocaine and heroin — laced with fentanyl.

Shold doesn’t believe that’s intentional. “Killing customers is not high on their list,” he says of drug dealers. Rather, he says dealers are often handling, measuring and bagging multiple types of drugs using the same equipment in the same facilities. But because fentanyl can be so dangerous in such small quantities, the results can be devastating.

“The audience we really wanted to focus on was people who were effectively ingesting fentanyl nonconsensually — meaning they didn’t think they were going to be ingesting it. They thought they were doing cocaine or they thought they were getting a Percocet pill off the street,” Shold says. “Those are the people that we are trying to help find a way to check their drugs, to make sure that they don’t contain fentanyl if they don’t want to be consuming fentanyl.”

He and Alison Heller created FentCheck in 2019 because, at that time, fentanyl testing strips existed but were difficult to find.

Prior to the passage of HB2395, the easiest place to get fentanyl testing strips was through syringe-exchange programs. But, Shold points out, not all drug users know about or regularly visit such locations. His organization has done outreach to nightclubs, dive bars and strip clubs, and he says a number of business owners have expressed interest — but have been reluctant because of the legal issue. (For his part, Davis says law enforcement have left him alone.)

The CDC estimates that about 150 Americans die every day from overdoses related to synthetic opioids. The Oregon Health Authority’s data dashboard on illicit fentanyl overdoses ends in 2019 but shows a slight drop in the number of deaths that year from the previous year — 62 deaths versus 73 in 2018 — after years of steadily increased deaths from 2015. The OHA says fentanyl is the most frequent drug involved in overdose deaths in Oregon, and that the amount of fentanyl seized by law enforcement in the state increased from 690 counterfeit pills in 2018 to more than 2 million in 2022.

Haven Wheelock has run Outside In’s syringe exchange for 17 years and has worked in harm reduction for more than 20 years, starting with HIV-prevention work in high school in 1998. She holds a master’s in public health from Johns Hopkins University, focusing on overdose and addiction policy.

“I love people who use drugs a lot,” Wheelock says.

Outside In’s needle-exchange program was one of the first in the United States, modeled on programs in Europe that were developed to curb the transmission of HIV through intravenous drug use.

Fentanyl “really has become dominant” in use in recent years, Wheelock says. In late 2021, there was a decline in the number of people coming in for injection equipment. The nonprofit has begun to offer pipes — partly to encourage people to smoke fentanyl rather than inject it, because the risk of overdose is much lower with smoking — as well as fentanyl testing strips. (After the print version of this story went to press, Willamette Week reported that Multnomah County had begun distributing pipes, along with foil and straws, to fentanyl users. Shortly after that story published, county officials said they’d suspend the program.)

“Fentanyl test strips are a relatively new intervention in the world of harm reduction. I mean, we’ve been using them for about 10 years as a harm-reduction community, but that’s still pretty new, right?” Wheelock says. “I don’t think when they were drafting [the drug paraphernalia law], they were thinking, ‘Oh, we’re going to keep people from inadvertently using substances that are dangerous, right? I don’t think their intention was to bar people from having fentanyl test strips. But it’s how it’s playing out today.”

Davis says the fentanyl epidemic has hit home just recently, with news reports that eight people in Portland overdosed in a single weekend in May and stories from friends working at other bars. And a little less than a year ago, he says, a regular customer who he considered a friend had a girlfriend who overdosed, and then overdosed himself the following day.

“Drug use has happened, to the best of my knowledge, ever since bars existed, and I’m just providing another tool for people to make an informed decision,” Davis says. “I’m not saying ‘Yeah, go ahead and do it’ or ‘No, don’t do it.’ It’s more, ‘You’re going to make your own decisions. Be safe about those decisions.’”

Click here to subscribe to Oregon Business.