Oregon’s glass bottle recycling rates may be some of the highest in the nation, but with the state’s only glass recycling plant temporarily shuttered, where is the rest of our used glass being carted off to? And is glass recycling as green as environmentalists once thought?

Oregon’s Bottle Bill, passed in 1971, is famous for being America’s first bottle bill. It was also the country’s first “extended producer responsibility” program, before that term was even coined. In the bill, legislators made beverage distributors (or manufacturers who self-distribute) responsible for reimbursing grocery stores for the refund value. Consumers then pay the deposit when they buy beer or other beverages, but they recoup that when they return the bottles.

The whole point of the deposit is to incentivize consumers to reliably return the bottles and cans — and it has worked. The Bottle Bill has undergone many updates over the years: adding bottled water (2009); the Green Bag program (2010); juice, tea, coconut water and other beverage containers (2018); and canned wine (2022). In 2017 the deposit doubled to 10 cents per bottle, resulting in a spike in returns. According to the Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative (OBRC), Oregon had a bottle redemption rate of 85.5% in 2022.

Nine other states have followed Oregon’s lead, but when it comes to cans and bottles, Oregon still has the highest recycling rate in the country. In August the Container Recycling Institute, a national beverage container recycling think tank, announced that Oregon’s redemption rate is the best in the nation, followed by Maine, with a redemption rate of 78%.

Much of this success has to do with OBRC, the not-for-profit formed in 2009 by Oregon beverage distributors to efficiently collect empty bottles and cans from retail partners and consumers and sort them by material. OBRC does this via 27 full-service redemption centers across the state, six of which are also processing plants.

“We have a statewide network for return infrastructure, the Green Bag program at redemption centers, all coming back through one fully integrated stream,” says Eric Chambers, vice president of strategy and outreach at OBRC. All of this means cleaner bottles and cans, which are a desirable commodity. The glass bottles that OBRC collects from across the state are crushed into “cullet” and sold to Portland-based glass recycler Glass to Glass.

But what about the glass that doesn’t have a deposit on it — the used pickle jars, peanut butter containers and wine bottles that Portlanders (and residents of other Oregon cities) put in our glass-only bins each week? None of those are collected by OBRC. And what do rural Oregonians who don’t have curbside recycling do with their used glass bottles?

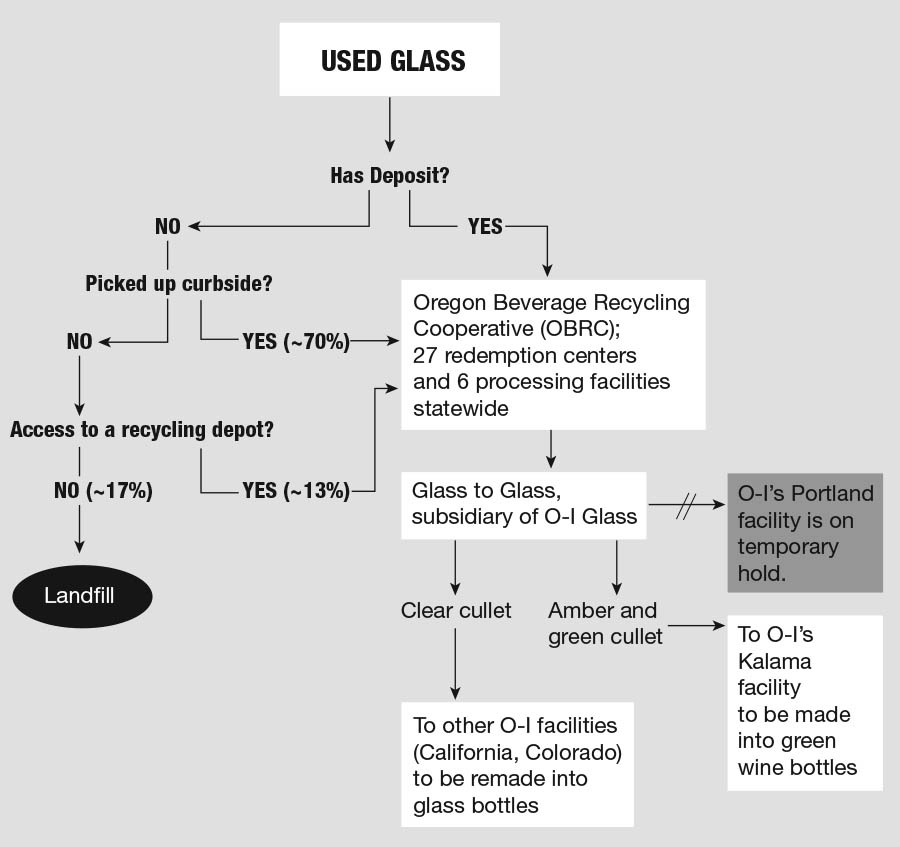

I’d heard whisperings that much of that glass ends up in landfill, since low-income Oregonians can’t afford to pay additional fees for recycling services — and some can’t easily drive to recycling depots. If that’s true, then glass, I realized, is not the environmental best choice many of us think it is. It takes a lot of energy to make. Glass cullet, limestone, sand and soda ash are heated to 2,600 to 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit; the process of making glass emits toxic pollution; and it’s heavy, which means it’s both expensive and puts more carbon into the atmosphere to truck it across the country. According to a 2014 study commissioned by the Wine Institute in California, glass bottles account for 29% of wine’s carbon footprint — the single biggest factor. (That’s not even factoring in that some winemakers order their glass bottles from China.)

Wanting to get to the bottom of where and how Oregon’s glass is recycled, I first called Bob Hippert, Sustainability Strategy Leader at O-I Glass, the Ohio company that owns Oregon’s only glass furnace. Hippert confirmed that all the glass that OBRC collects at six of its processing plants around the state is crushed, then taken to an O-I subsidiary, Glass to Glass, where the cullet is sorted into three different color streams: amber, green and clear. Typically, the sorted cullet is sent to the O-I Glass plant, five miles down the road, but since midsummer, that facility has been on a “hot hold.” (Hippert says that’s due to a lack of interest from the Oregon wine industry in recycled-glass wine bottles, which is what the plant typically makes.) Instead, the amber and green cullet is currently going up to O-I’s facility in Kalama, Wash., 45 minutes north, where it’s used to make green wine bottles. Currently, the flint (clear) cullet is being shipped to out-of-state O-I plants—typically in California and Colorado—and remade into glass bottles there.

Hippert sings the praises of OBRC, which recovers 45,000 tons (90 million pounds) of glass from Oregonians every year. “Oregon is the best state in the country as far as recycling glass,” he tells me. “I wish I had 50 Oregons around the country. We wouldn’t be struggling to hit some of our aspirational goals when it comes to recycled content.”

When Portland’s O-I Glass plant was operational, it made bottles with 70% recycled glass — a very high percentage. (The industry average in recycled glass bottles is nearly 40%.) Lange Estate Winery in the Willamette Valley is a client; winemaker Jesse Lange says he’s proud to support domestic glassmakers. In June 2023, the O-I plant in Portland laid off 81 employees and began a “hot hold” of its furnace. In 2021 regulators at the state Department of Environmental Quality fined the company $1 million for repeated air quality violations at its Portland facility. O-I agreed to install new equipment to control pollution (and the DEQ reduced the fine to $662,000), but Hippert insists that’s not the reason for the hot hold. (The company was fined another $213,600 in August for violations from July 2022 and this past May.) The company needs to install pollution controls by May 2024, per their 2021 settlement with the DEQ.

But, I realized, I still didn’t know where our non-Bottle Bill glass goes. Oregon Metro — the regional government elected by voters in Multnomah, Clackamas and Washington counties to oversee land use and waste collection in the greater Portland area — sets the standards for recycling and manages the trash and recycling system in cooperation with local governments, which award contracts to haulers. So I called Rosalynn Greene, the strategic initiatives director at Metro’s Waste Prevention and Environmental Services department. Metro has two transfer stations: one in Northwest (Metro North) and one in Oregon City (Metro South). But those only process a fraction of the Portland area’s trash. Trash haulers — including Heiberg, Portland Disposal & Recycling Inc., and Waste Management of Oregon — are the entities that collect our trash and our glass (at least in the Portland area). Heiberg sells its glass jars and bottles directly to Glass to Glass; glass containers collected by Waste Management are taken to Environmental Fibers International and Far West Recycling, both of which deliver it to Glass to Glass. Outside of the Metro area, San Francisco-based Recology collects glass curbside in 30 Oregon cities and counties — including Ashland, McMinnville and Tillamook County. It also operate material recovery facilities (MRFs) and recycling drop-off depots. All of the glass it collects is consolidated at Recology transfer stations and then transported to O-I’s Glass to Glass facility in the Portland area. So far, it was sounding like most of Oregon’s glass — at least the glass that’s collected curbside — is sold to Glass to Glass, to be made into new bottles either in Kalama, Wash., or O-I plants in other states.

The U.S. has an abysmally low glass recycling rate: 31.3% of glass is turned into a recycling program according to the Environmental Protection Agency. In Oregon that number is better: 75% according to the DEQ. (That figure includes Bottle Bill recycling.) Part of that has to do with the Bottle Bill infrastructure, but also it has to do with Metro fighting for a separate glass bin, at least in the greater Portland region.

“We have advocated for it and required local governments to separate glass because of the material quality issue,” says Metro’s Greene. Even in Seattle, which is in a Bottle-

Bill state, residents throw their glass into a mixed-recycling bin. “As you can imagine, when all the materials go to a MRF [Materials Recovery Facility], it’s hard to pull out glass from paper when it’s wet,” Greene says. “There are issues when it’s commingled and getting that material out of it.”

When people throw everything from soiled food containers to used Keurig pods into the commingled bin, the glass ends up in a sorry state. So in states that don’t have a separate sorting mechanism for glass, the dirtier glass from MRFs ends up as cover for landfills (literally, a top layer to keep other trash from blowing away), according to Peter Spendelow, a natural-resource specialist at the DEQ.

“That’s a pretty worthless use,” he says. The clean stream of glass OBRC and trash haulers supply to companies like Glass to Glass means that most of Oregon’s glass actually gets recycled and not thrown into landfills.

According to the DEQ, about 70% of Oregon’s population has access to curbside recycling and another 13% has access to depots only, where people can drop off their recycling. That leaves 17% of Oregonians who don’t have convenient access to glass recycling of any kind. In those remote corners of the state — places like Malheur or Lake counties — it’s likely that most people’s trash ends up in the landfill. (These figures do not include Bottle Bill glass, which OBRC collects weekly in all parts of the state.)

The consistency of recycling across the state will improve when the new Recycling Modernization Act goes into effect in 2025. Passed during the 2021 Oregon legislative session, the RMA is a producer-responsibility law that will require the formation of producer-responsibility organizations (PROs) that will be responsible for making sure their packaging materials are recycled in “responsible end markets.” (Rule-makers are still working out how to enforce this.) The RMA will expand recycling services across the state, upgrade recycling facilities, and create a uniform statewide collection list so that whether you live in Burns or Astoria, the same materials will be collected for recycling. In November, rule-makers at the DEQ approved a uniform statewide collection list.

One of the things that makes glass superior as a packaging type is that it can be recycled an infinite amount of times.

“There’s not a maximum amount of times glass bottle can be remelted,” says Hippert at O-I. But even better for the environment than recycling glass is refilling it, which you can do up to 50 times. In 2018 OBRC launched a refillable bottle program for beer bottles.

“Because of our high redemption rate, and our vertically integrated system, we have a high degree of confidence that they’d come back into our system,” says Chambers at OBRC.

OBRC created two custom bottles (12 ounce and 500 ml, both made by O-I) embossed with the words “Bottle Drop” and debossed with the words “Refillable” and “Please return.” Right now they have 11 partners, mostly brewers, including Double Mountain, Gigantic, Ancestry and Buoy. They even have two winemakers — Pierce Wines and Coopers Hall Wine — and one cidermaker, Röder Apfelwein. Collectively, these 11 partners have 137 individual SKUs in the OBRC system totaling 2.8 million refillable bottles. While that’s a small percentage of the overall market, it’s the only statewide refillable-bottle program in the nation. For Chambers, this pilot project is proof of concept.

One of the biggest evangelists for refillable bottles (and also OBRC’s first refillable partner) is Matt Swihart of Double Mountain Brewery in Hood River. He’s done his homework. Experts he’s interviewed say that not only do refillable glass bottles have a 90% lower carbon footprint than single-use bottles, they are far superior to aluminum cans, which rely on bauxite (a rock that needs to be strip-mined from the earth) and are lined with plastic. Finally, he says, beer out of glass bottles tastes better, because less oxygen gets in during the bottling process. On the OBRC website, Swihart explains a big perk of the refillable-bottle program during COVID: “During the pandemic, almost every brewer I knew was panicking [about] package supplies with shortages of both aluminum and glass,” Swihart said on the OBRC site. “But we’ve been great with a bunch of stock in Clackamas, so we haven’t had major interruptions or changes in pricing.”

The same supply-chain issues hit the wine industry. Chinese-made wine bottles were either stuck in ports or delayed due to pandemic shutdowns, which meant, in many cases, that U.S. winemakers couldn’t bottle their wine. A new venture has sprung up to offer a local refillable wine bottle program here in Oregon — at a much larger scale. Keenan O’Hern and Adam Rack are the passionate duo behind Revino, which will be introducing a refillable wine bottle in the Willamette Valley in 2024.

There are many reasons why winemakers want refillable bottles: One, they want a reliable supply of locally made glass. (The Revino bottle will be made by O-I.) Others want the bottles for environmental reasons. That’s the case for Donna Morris and Bill Sweat at Winderlea Vineyard & Winery, who have been working to find a lighter bottle. (The heavier the bottle, the higher the carbon emissions.) In 2006, when they made their first vintage, their bottles were 830 grams. The ones they order from Saverglass’ facility in Mexico are 600 grams. Revino’s will be 495 grams. They plan to start using Revino bottles for a few select wines they sell in the testing room, but hope to go big as Revino grows. “It would be our goal that 100% of our glass will be in refillable,” Sweat says.

Pat Dudley at Bethel Heights Vineyard, who is a co-founder of the Oregon Oak Accord (her husband, Ted, founded the LIVE Certification), is also switching to Revino, at least for four wines the winery serves exclusively in the tasting room.

She says the concept has been proposed in the Valley before but the hurdles have thus far been insurmountable. “I hate to say this, but I think one of the main holdups has been the attachment of winemakers to the bottle styles,” she says. The other challenge is re-collecting the bottles. Both of those would be solved by Revino.

When Revino is up and running this spring, it’ll have regular collection routes through the Willamette Valley. The company, which already has its first van, will collect empty Revino bottles from tasting rooms and take them to a facility to wash them. (O’Hern and Rack will store the bottles at a warehouse until their wash facility is up and running.) Wineries would receive a credit on future glass purchases for each bottle returned through Revino’s pick-up route. The duo estimates that a case of Revino bottles will cost $12. O’Hern and Rack are also in discussions with OBRC to include Revino bottles in the OBRC return system. If that happens, then any consumer could return their Revino bottle to an OBRC redemption center, and OBRC would sort them out from other bottles. Revino would then pick up the bottles from OBRC and send them to their own facility for cleaning.

The second hurdle — wine bottle style — is something that O’Hern and Rack are working on. They plan to have one style initially: an antique green Burgundy bottle (both cork and screw-cap finishes). But depending on interest from the Finger Lakes wine region and other areas they’re in talks with, they may do a Bordeaux-style bottle or a riesling bottle after that. A sparkling-wine bottle may even be on the horizon. “We’ll let the market and winery partners influence our decisions,” Rack says. Ultimately, if all goes well in Oregon, they hope to have multiple facilities across the country so that eventually wineries could use refillable Revino bottles even for their far-flung wine-club sales.

Dudley thinks Oregon winemakers are finally ready to embrace this refillable program and notes that in Europe, these programs have been in place for a long time. “I think there has been enough push in that direction [sustainability] that winemakers are starting to feel obliged to give up that silliness about the bottle weight and the bottle shape,” Dudley says. “Let your label be your brand!”

Many prestige Willamette Valley brands, in addition to Bethel Heights and Winderlea, have committed to ordering Revino bottles including Adelsheim, Brick House, Brooks, Cameron, Illahe, Walter Scott and Soter. So far 56 winemakers from up and down the Willamette Valley have signed on with 60+ more showing interest.

O’Hern, whose mom is Dutch, grew up regularly visiting Holland, where no one thinks twice about bringing their reusable glass bottles back to the store. “It’s just a way of life over there. You put it back in the crate, bring it back to the shop and they wash it and reuse it,” says O’Hern, who got his MBA at George Fox University and has worked in digital marketing education and as a management consultant. Rack was the operations manager and assistant winemaker at Coopers Hall, an urban winery and wine bar that has exclusively put wine in kegs since it opened in 2014. (Thanks to Rack, it also joined the OBRC refillable program in 2019 with Coopers Hall wines.)

With glass prices continuing to rise, using the same wine bottle over and over again also makes financial sense for wineries. “If you think about it, the glass wine bottle has value already,” says Rack. “We wash our glassware, we wash our wine glasses. We pay a lot of money for them. Pint glasses at a restaurant or wine glasses are used hundreds of times! These bottles that don’t break when you throw them in the trash because they’re so heavy and thick—we throw them away. And they’re gone. There’s value there!”

Click here to subscribe to Oregon Business.