The promise of prosperity hasn’t come true for Oregon’s rural communities.

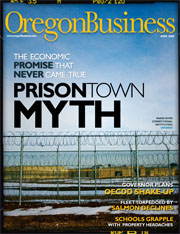

PRISONTOWN MYTH

PRISONTOWN MYTH

The promise of prosperity hasn’t come true for Oregon’s rural communities

By Ben Jacklet

The facility sits on a sweeping expanse of land so remote that it is difficult to determine the nature of its business without moving closer to investigate. Only then do the details come into focus: sniper towers, a firing range and spirals of razor wire extending into the horizon.

This is the Snake River Correctional Institution, Oregon’s largest prison, home to 3,000 inmates. Watching over these inmates, feeding them and caring for them, are 872 state employees, 1,000 if you count the contract jobs, putting the Snake River Correctional Institution even with the Ore-Ida plant, where the Tater Tot was invented, as the largest employer in Malheur County.

|

Down in the center of Ontario, population 12,000, there is no sign of the prison. But its economic presence is palpable, even at the coffee shop owned by one of its biggest former critics. Todd Heinz, who owns Making Tracks Cyclery and three Jolts & Juice coffee shops, led an unsuccessful recall effort to oust the local officials responsible for turning Ontario into a prison town in 1991. Today he is having coffee with two of his best customers, both 27-year veterans of the corrections industry, and his views on the prison have changed profoundly.

“There were a lot of opponents when it was being built, me being one of them,” says Heinz. “But it’s a huge part of our economy. If you were to pull that prison out of here now the impact would be disastrous.”

Support for the prison is nearly unanimous within Ontario’s business community. The prison brought jobs that did not exist previously: stable, relatively high-wage positions with full benefits. Local people doubled their salaries. New residents moved in with money to spend. The hospital got new patients and the community college grew. Business picked up at the taco stand, the tire repair shop and the hardware store as healthy state salaries worked their way through the local economy.

Ontario is not alone. Since 1985, Oregon has expanded its prison system from three institutions based in Salem to 14 prisons scattered throughout the state, many of which were built in economically depressed, remote cities such as Ontario, where land is inexpensive and jobs are welcome. From Lakeview to Umatilla to Madras, business leaders praise their new prisons as stabilizing tools of development.

It is hard to find a business owner in Ontario or Umatilla who questions the wisdom of having a prison as the city’s largest employer. In Umatilla, where the president of the Chamber of Commerce works at the Two Rivers Correctional Institution, local business owners, such as Cathy Putnam of Carlson Drug, can’t find anything negative to say about the prison that dominates the local economy. “You have people with jobs that are spending their money,” she says. “I don’t see a downside.”

John Breidenbach, executive director of the Ontario Chamber of Commerce, says, “The prison has been here for 15 years, and it has stimulated our economy.”

|

But travel a few blocks away from Ontario’s downtown, and you will find abject poverty: dilapidated shanties, rusted-out cars and trailers parked amid towering piles of old tires and garbage. Before the prison opened in 1991, Malheur County was one of the poorest counties in Oregon. Today it is the poorest, with 21% of the county’s residents living in poverty.

The prison brought jobs, but it did not bring prosperity.

OREGON EXPANDED ITS PRISON system dramatically during the 1990s, partly because of national trends toward stricter sentencing and partly because of the state’s defining tough-on-crime law, Measure 11, which passed in 1994 and established mandatory minimum sentences for violent criminals. Since 1990, Oregon has built seven correctional facilities and more than tripled the budget of the Department of Corrections (DOC). Oregon already spends a larger percentage of its general fund on prisons than any other state, and that expense could grow as voters this fall consider stiffer new sentencing laws that could again swell the prison population.

During the prison boom of the 1990s, the DOC was able to overcome local resistance by touting the economic benefits to municipalities struggling to recover from the downfall of Oregon’s natural resources economy. For those communities, a prison where the median wage is $3,849 per month is seen as a prize rather than a burden.

|

But recent research shows that prisons are not effective tools of rural economic development. A phalanx of researchers from the University of Colorado at Denver, Pennsylvania State University, Washington State University, Ohio State University and the Washington, D.C., nonprofit organization The Sentencing Group analyzed data from across rural America and concluded that prisons do not significantly improve employment rates, poverty rates or median incomes. No studies have focused solely on Oregon, but based on economic statistics from Umatilla and Malheur counties, the Oregon counties that rely most heavily on prisons, these conclusions hold true there as well.

The national studies cite a number of problems with using prisons to boost economies. First, prisons do not pay local taxes. Second, they rarely if ever purchase goods and services locally, and while they sometimes try to hire locally, they do not always succeed because of union requirements that promotions must be based on seniority. Third, prison employees tend not to live near their place of employment, preferring to settle in outlying areas and commute. For example, 62% of the employees from the Ontario prison don’t live in Oregon but next door in Idaho, where property taxes and home prices are lower.

Finally, prisons supply inmate laborers at low or no cost, taking jobs away from the local community.

Finally, prisons supply inmate laborers at low or no cost, taking jobs away from the local community.

In addition to those specific shortcomings, there is the broader notion of “opportunity costs,” the cost of pursuing one choice rather than another. The idea is that operating large prisons in small, remote towns requires so much accommodation that it crowds out other opportunities that might lead to clusters of related, competing businesses propelling each other to innovate and expand. In other words, there is nothing entrepreneurial about a prison economy.

Academic researchers aren’t the only ones re-evaluating the economic promise of prison expansion. Max Williams, director of the Oregon Department of Corrections who was appointed by Gov. Ted Kulongoski in January 2004, says it is a misnomer to think of prisons as an engine of economic development.

“We are not a profit center,” says Williams. “We are a cost center. We’re taking tax dollars that could be spent on a whole variety of things, and we’re spending them on prisons.”

“We are not a profit center,” says Williams. “We are a cost center. We’re taking tax dollars that could be spent on a whole variety of things, and we’re spending them on prisons.”

This is a significant reversal for the DOC, which promoted prisons as catalysts of development during the prison-building frenzy of the past 20 years. Williams says he would prefer to spend less money on prisons and more on “evidence-based” solutions to crime. But the DOC’s steps toward reining in spending on prisons are jeopardized by the looming prospect of two prison initiatives on the ballot in November.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Both initiatives would increase spending on corrections. The more expensive measure, backed by Republican activist Kevin Mannix, would set up mandatory prison sentences for first-time property and drug criminals, adding a projected 4,000-6,000 inmates to Oregon’s prison system at an annual cost of $128 million to $200 million. There currently are 13,500 inmates in the state. Legislators reacted to that imposing price tag by cobbling together an alternative measure that would focus on punishing repeat offenders and expanding drug treatment programs. Their less-expensive alternative would still add about 1,400 new inmates at a cost of $52 million annually.

If both initiatives pass, the one that receives the most votes will become law. If history repeats itself, the odds are with Mannix. More than 150,000 Oregonians signed the petition to put Mannix’s measure on the ballot, and the state’s voters have a history of embracing tough anti-crime measures.

It’s unclear exactly how the state would house the flood of prisoners that would accompany the Mannix initiative, but the DOC would have to move quickly to make room; new prisoners could start pouring into the system next March. The DOC owns undeveloped property in White City, outside of Medford, and has preliminary plans to build a 2,000-bed prison in Junction City. But the department’s construction plans were based on forecasts that did not consider the thousands of extra inmates that would result from harsher sentencing laws.

THE OREGON STATE PENITENTIARY was built in Portland in 1851 and relocated to Salem in 1866, where it remained the state’s only major prison for 100 years. Other facilities were built to supplement the penitentiary’s mission, but with the exception of a forest work camp in Tillamook, Oregon’s prisons were confined to Salem until 1985, when the Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution opened in Pendleton.

Then came the great expansion: the Powder River Correctional Facility was completed 350 miles east of Salem in Baker City in 1989, followed by a barrage of prisons named after bodies of water rather than towns: Mill Creek, Columbia River, Shutter Creek, Snake River, Two Rivers, Coffee Creek and Warner Creek. With the opening of the Deer Ridge Correctional Institution in Madras last October, Oregon’s prison industry has grown to 14 facilities, 13,500 inmates, nearly 5,000 jobs and a DOC budget of $1.26 billion. The state now spends more on prisons than on higher education.

As the new prisons were built, wages in rural Oregon stagnated. So it’s not surprising that rural communities have embraced prisons and the jobs they bring. “There’s not a lot of industry knocking at your door in these rural areas,” says Oregon Employment Department regional economist Dallas Fridley, who tracks North Central Oregon. “Given the isolated nature of some of these communities, there may not be that many options for development beyond a prison.”

State economic development specialists were intimately involved in DOC’s selection process. A brochure sent by the DOC to Madras residents in 2002 prior to the construction of the Deer Creek prison promoted jobs, training and business opportunities. The DOC commissioned economic impact studies to win over local officials with promises of jobs and economic development. But it has not studied whether those promises have been kept.

Employment and income numbers indicate that Oregon’s massive investment in prison expansion has brought local gains that are modest at best. The rural counties that gambled biggest on large prisons after the passage of Measure 11, Malheur and Umatilla, have continued to struggle. In Malheur County, non-farming jobs have increased slightly since the completion of the Snake River prison, but wages have been sluggish. Malheur County has the state’s highest poverty rate, its lowest median income, and is 31st out of 36 Oregon counties in earnings per job.

Employment and income numbers indicate that Oregon’s massive investment in prison expansion has brought local gains that are modest at best. The rural counties that gambled biggest on large prisons after the passage of Measure 11, Malheur and Umatilla, have continued to struggle. In Malheur County, non-farming jobs have increased slightly since the completion of the Snake River prison, but wages have been sluggish. Malheur County has the state’s highest poverty rate, its lowest median income, and is 31st out of 36 Oregon counties in earnings per job.

The situation also looks grim in Umatilla, where the main street through downtown features boarded-up storefronts, vacant lots, run-down $25-a-night motels and sprawling trailer lots in varying stages of decay. In Umatilla County, state jobs grew after the Two Rivers prison opened in 2000, but private sector jobs fell and wages have held flat. The 430 employees of the Two Rivers Correctional Institution, by far the largest employer in the City of Umatilla, spend money locally, but the prison does not. Of the $56.6 million that DOC spent to purchase goods and services for its prisons in 2007, only $29,928, or .05%, went to Umatilla businesses.

Local purchasing figures are only slightly higher in Ontario, an agricultural center for potatoes and onions. Mark Nooth, superintendent for the Snake River prison, explains that the facility’s hands are tied when it comes to supporting local business.

“We’re too big,” Nooth says. “We serve 9,000 meals a day. Local businesses can do a portion of it, but we need someone who can handle the whole thing.”

Statewide, just 42.5% of the goods and services used in prisons are purchased from Oregon companies.

Then there is the matter of prison labor. In 1994, the same year Oregon voters passed Measure 11, they also approved Measure 17, which requires inmates to work a 40-hour week. As a result, Oregon prisoners work inside and outside of their facilities, cleaning parks, sorting mail, printing business cards, building cabins and making telemarketing calls for private companies, including Timeline Industries and National Marketing Solutions.

At the Eastern Oregon Correctional Facility in Pendleton, inmates produce the Prison Blues brand of jeans for the Array Corporation, a division of Portland-based Yoshida Group. In Ontario, minimum-security inmates sort potatoes bound for the Ore-Ida factory and spruce up the Four Rivers Cultural Center, the location of the Ontario Chamber of Commerce. In Umatilla inmate crews work at the Finley Butte Landfill and unload rail cars for CRL, a subsidiary of the Denver-headquartered Broe Group.

Larry Clucas, Umatilla’s city manager, frequently hires inmate crews. “Yeah, they’re jobs that might have been taken away from somebody,” he says, “but realistically they probably wouldn’t have gotten done.”

That may be true for menial tasks, but prisoners also fill jobs that might otherwise provide meaningful income. In Umatilla and Ontario prison laborers helped expand the prison to make room for more inmates, a project that might otherwise have been filled by well-paid construction workers working for an Oregon contractor.

DOC director Williams emphasizes that Oregon Corrections Enterprises, which oversees prison work programs, studies each contract to make sure jobs are not being taken from the community. He also points out that, while prisons do not pay taxes, they do pay a negotiated portion of the costs to expand utilities, which often enables municipalities to do needed upgrades to sewage systems and other infrastructure. But the most important asset the DOC brings to communities where the prisons are built, Williams argues, is the employees.

“We’ve been able to win communities over by the way we run our facilities and the people we hire,” he says.

|

PRISON EMPLOYEES MAKE good money, especially in comparison to what other jobs pay in Ontario and Umatilla. Rather than just scrambling to pay the bills, there are some prison workers with entrepreneurial leanings and discipline who are able to save enough capital to go into business for themselves.

Ron Rouse worked for the Ontario prison for 17 years, starting at $1,500 per month and working his way up through step increases and promotions to nearly $6,000 per month, enough to support a family of five children, a nephew, plus a “kid from the neighborhood who came to stay with us and never left.”

Rouse and his wife, Sandra, worked two jobs for two years and poured their savings into building a Gandolfo’s Deli franchise in Ontario to serve the lunch crowd from the prison, as well as shoppers who cross from Idaho to Oregon to avoid paying sales tax. They plan to open seven sandwich shops over the next seven years.

Rouse says the entrepreneurial spirit is not unusual among his friends from the prison. Other prison employees raise cattle, run service companies and invest in rental properties. “There’s so much talent to pull from the prison, and it brings so many new things into the community, it’s just phenomenal,” says Rouse.

Tony Shaver is another example. He was one of the first 75 people hired to work at Snake River, doubling his salary. That was in 1991, when it was a small minimum-security facility. Since then the prison has vastly expanded, and Shaver has increased his earnings in sync, enabling him to buy six rental houses as well as his own house in New Plymouth, Idaho.

After 16 years on the job, Shaver bought a local business in the north end of town, TRS Plumbing. “I always had ideas, but I never had the means,” he says. “The prison gave me the means.”

But business is slow, Shaver admits. “I went from earning $4,200 a month to no income,” he says. “It’s a good thing my wife works.”

Unfortunately, Shaver’s business is located on the opposite side of town from a Home Depot that is better positioned to snag shoppers flowing in from Idaho. In that regard, Shaver may be a victim of the same prison economy that allowed him to start his business. Studies show that the tendency of prison employees to make good money and drive great distances to work has not escaped the attention of big-box retailers, which have followed new prisons into rural America, often to the detriment of locally owned businesses.

|

FOR EVERY REMOTE TOWN in Oregon that got a prison during the 1990s, there is another that did not. One municipality that tried to bring in a prison several times only to lose out to Ontario and Umatilla was Boardman, in Morrow County. In 1989, when the DOC was trying to locate the prison that eventually was built in Ontario, Morrow County’s unemployment rate was 16.5%, the highest in Oregon.

“Our economy was in tough shape,” recalls Gary Neal, general manager of the Port of Morrow. “We thought it might be a good fit to create some good-paying jobs. But folks didn’t want a prison. We heard that loud and clear. At the time I was disappointed. But I just went on and looked for the next opportunity.”

Rather than floundering after failing to attract a prison, Morrow County’s economy has steadily improved, particularly at the sprawling industrial properties of the Port of Morrow, which is now Oregon’s second-largest port. Two gas-fired power plants run cooperatively by Portland General Electric and Avista pump out power. Two major factories broke ground last fall: a Pacific Ethanol plant that is Oregon’s first fuel refinery and a joint venture involving R.D. Offutt and the Japanese food company Calbee to make potato snacks for Japanese consumers. Portland-based Greenwood Resources is spending $35 million on a new sawmill and a dry kiln to produce sustainably harvested timber. The Tillamook County Creamery Association has invested $100 million in Morrow County and will soon have the capacity to make twice as much cheese here as in Tillamook County. There are two parcels of land leased out to speculating biofuel companies, a staging area for wind turbines and a proposed NASCAR track that could draw thousands of racing fans. It adds up to about 1,000 new jobs on port property created since Boardman lost out to Ontario for a prison.

It is impossible to know whether the lack of a prison helped spur the diversification of the Port of Morrow. Furthermore, it would be a stretch to describe Boardman — population 3,500 — as a boomtown, with just two real estate companies, one grocery store and a median home price of about $100,000. But jobs are being created in Boardman and clusters are forming in the specialty food and renewable energy sectors. Private employment grew by 27% from 2000 to 2006. During that same period, neighboring Umatilla County, home to two large prisons, lost 1,460 jobs in the private sector.

In 1989, Umatilla County had a higher median household income than Morrow County, $23,207 to $22,944. By 2005, Morrow County’s median income had jumped to $43,776, well ahead of Umatilla County’s median of $39,003.

The income numbers are far lower in Malheur County, which beat out Boardman in the contest to host Oregon’s largest prison. Local leaders in Ontario say they do not regret welcoming the prison and the stable jobs it brought. But they acknowledge that the prison did not solve the ingrained problems that stem from the downfall in agricultural jobs and generational poverty.

With that in mind, they are freeing up agricultural land for development, hoping to attract new businesses — preferably a large employer that pays as well as the prison, but one that is different from the prison. They nearly succeeded in 2003, when Gov. Kulongoski traveled to Ontario to announce the impending arrival of an innovative biorefinery to be built by Treasure Valley Renewable Resources. But the deal fell through before construction began, and Ontario’s search for new jobs continues.

“We’ve got huge parcels of land, we’ve got tax benefits, and we’ve got people who are looking for work,” says Jim Jensen, a former president of the Malheur Bell phone company and the director of Malheur County Economic Development Department. “We need to attract new companies to the area so we can raise the bar.”

After 17 years of living with the prison, Ontario is left looking beyond the facility to find the answer to its economic troubles. As Oregon considers pouring even more money into prisons, turning more rural communities into prison towns, the question remains: Is it worth it?

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]

Todd Heinz, who owns three coffee shops and a bicycle store in Ontario, opposed the prison initially, but not sees it as a vital source of jobs.

Todd Heinz, who owns three coffee shops and a bicycle store in Ontario, opposed the prison initially, but not sees it as a vital source of jobs.