Conflicting economic forecasts point to the need for more analysis in a data-saturated age.

Conflicting economic forecasts point to the need for more analysis in a data-saturated age.

BY LINDA BAKER

In our data-saturated age, reporters, business owners, and policy makers are inundated with economic forecasts that monitor changes in housing starts, unemployment, consumer confidence, manufacturing etc. Such indicators are intended to guide executives and government officials as they make decisions based on their view of the future. Increasingly, economic forecasts are also mined for political cachet. As the Daily Beast’s Daniel Gross observed yesterday, it was the much-hyped September Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs report — companies added 114,000 jobs that month — that gave Obama his winning edge.

In our data-saturated age, reporters, business owners, and policy makers are inundated with economic forecasts that monitor changes in housing starts, unemployment, consumer confidence, manufacturing etc. Such indicators are intended to guide executives and government officials as they make decisions based on their view of the future. Increasingly, economic forecasts are also mined for political cachet. As the Daily Beast’s Daniel Gross observed yesterday, it was the much-hyped September Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs report — companies added 114,000 jobs that month — that gave Obama his winning edge.

“It was the single most consequential economic data point in recent political history,” Gross wrote. The “unemployment data turned out to be (Obama’s) impregnable fortress.”

Having a job determines consumer confidence, the housing market and other economic activity. But how to determine the value connected to the abundance of other economic data? Do economic forecasts, which appear with increasing frequency, provide an accurate picture of the economy and where it’s headed? Or are they so much noise, especially in a recession and recovery that has confounded all predictions?

Consider three Oregon economic forecasts released this past week and dutifully reported by the news media:

October 30: a Federal Reserve report predicts that Oregon’s economic growth through March is expected to be among the fastest in the U.S. The Philadelphia Fed says the Oregon Coincident Index, based on housing permits, unemployment insurance claims, manufacturing data and interest rates, is poised to expand by more than 4.5 percent over the next six months.

November 1: Another positive sign, albeit with a disclaimer, this time from Oregon’s Economic Insecurity Index, which fell 5.8 percent in 2011. The gauge measures the share of Oregonians that lost at least 25 percent of available household income in a single year. Despite the good news, the report shows that economic insecurity in Oregon remains higher than the national average.

November 5: Some bad news from a University of Oregon gauge, showing that the state’s economy retreated in September, dampened by one of the steepest monthly jobs losses — 7,900 — since the recession. To calculate Oregon’s growth, the UO gauge uses a variety of factors, including manufacturing data, home permits, consumer sentiment and hiring among a handful of industries.

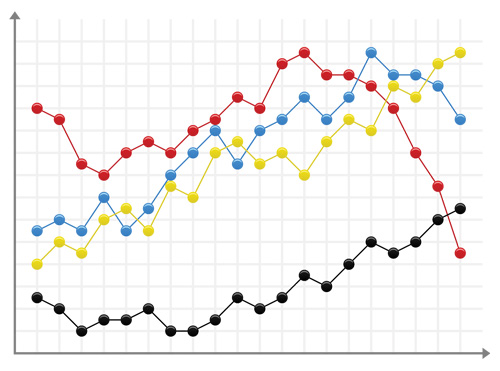

Collectively, these three reports present conflicting, or ambiguous, pictures of economic trends. One suggests the economy is expanding rapidly, another claims household income is declining at a slower pace while noting that economic insecurity is still high, and yet another documents a slower than normal expansion. How to make sense of the different forecasts and how to decide which one is the best predictor of economic trends?

“You use mine,” joked Tim Duy, the University of Oregon economist who compiles the monthly UO forecast. I talked to Duy yesterday and he agreed proliferating economic data presented something of a conundrum. The key to making sense of economic forecasts, he said, is understanding the context behind the numbers, recognizing what the indicators measure and understanding that most economic forecasts provide a snapshot in time, not an analysis of long term trends.

For example, Duy said the economic insecurity index measures impacts on lower income households. “How useful is that to a business person a firm owner — I would think not particularly useful,” he said. On the other hand, policy makers trying to understand the needs of low income Oregonians would likely find that information meaningful.

The federal reserve data projects rapid economic growth in Oregon. But it’s important to know that the latest (September) report is responding primarily to a rapid increase in building permits, Duy says. What’s more, he said, three months earlier, that same index “pointed toward recession territory.”

“You have to know the context and you’re only going to know the context if you’re someone like me,” said Duy. The economic “truth,” he says, is probably somewhere in between July’s gloomy assessment and September’s more positive outlook: Oregon’s economy is growing “but probably not at a super fast pace.”

Duy’s own chart documents a steep increase in job losses to suggest a slowing of the economy. But Duy himself notes that the state’s employment data is volatile, and that “the general story my index is telling is that things are getting better.” Or, as Duys says of his own monthly forecast: “it’s a snapshot of the available data, but the data is in flux.”

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to understand that that value of a given economic forecast depends less on the individual forecast than how it fits into long term trends. But if that conclusion is a no brainer, it also flies in the face of a world that is less a coherent whole than a growing mountain of data.

As Gross pointed out, in the presidential election, virtually every data point — about home prices, car sales, consumer confidence — became a point for or against one candidate’s larger political position. But if Duy’s analysis of this past week’s economic forecasts harbors a message, it’s that every economic forecast should come with a disclaimer. Warning: in the information age, data is not the same as knowledge.

Linda Baker is managing editor of Oregon Business.