The stakes are high for Oregon tribes, private business investors and the state in the race to get a casino close to the lucrative Portland market.

The stakes are high for Oregon tribes, private business investors and the state in the race to get a casino close to the lucrative Portland market.

|

Stanley “Buck” Smith (left), tribal chairman for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, and Louis Pitt, the tribe’s director of government affairs and planning, have been lobbying for a casino in Cascade Locks for nearly a decade. // PHOTO BY ANTHONY PIDGEON |

BY BEN JACKLET

The signs of the economic times are impossible to ignore as Louis Pitt and Bernard Seeger roll from one end of Cascade Locks to the other, past the high school that recently shut down, the housing development that has stumbled into foreclosure and the lumber mill that has laid off its workforce indefinitely.

At first glance the two men seem an odd couple. Pitt, the director of government affairs and planning for the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs, is a hulking but soft-spoken Native American with long, dark hair and a deep, easy laugh. Seeger, city administrator for Cascade Locks, is a wiry, intense West Point graduate who runs the Pacific Crest Trail for recreation when he isn’t trying to run a city on limited resources. Pitt chuckles at the notion of running for fun; he prefers golf. But in spite of their completely different heritages and personalities, the two men share a strong conviction that a new casino in the Columbia River Gorge would do wonders for their constituencies, and for Oregon’s ailing economy.

Web-only content: More on Oregon Gambling |

|

At the far end of town they reach their destination: 25 acres of grass and oak trees next to the highway, a former lumber mill zoned light industrial. Nine million cars drive past this location each year. This is where the Warm Springs and Cascade Locks have been trying for nearly a decade to build a new tribal casino within 45 minutes of downtown Portland. They say the project would bring 400 construction jobs, 1,700 year-round jobs, $850 million for college scholarships, and $85 million for environmental restoration and economic development in the Columbia River Gorge — not to mention a road to economic self-sufficiency for the tribe and a ticket out of post-timber small-town depression for Cascade Locks. After years of opposition and delays, they recently earned preliminary approval from the federal government, and a final “record of decision” could come any day.

At least that’s how Seeger and Pitt prefer to see it. “We’ve been beating on this dog for so long,” says Seeger. “There’s not a flea left on it.”

“We’re getting real close,” adds Pitt. “If this were a football game we’d be in the two-minute drill.”

But time could be running out. Environmental groups such as Friends of the Gorge remain steadfast against the casino, as do competing tribes and, perhaps most significantly, both candidates for governor. The jackpot is undeniably lucrative, but the odds are long for anyone hoping to change Oregon’s gambling status quo. And the Warm Springs and Cascade Locks are not the only players angling for radical changes.

A pair of Lake Oswego businessmen have partnered with a Las Vegas consultant and a Canadian investment firm in a bid to turn an abandoned former dog track in Wood Village into a $500 million casino and entertainment center, with rooftop gardens and an indoor/outdoor water park along with more slot machines than the largest casinos in Las Vegas. Also in the game is the Cowlitz tribe, which is working to set up a reservation anchored by a huge casino in La Center, Wash., backed by one of the wealthiest gaming tribes in the nation, the Mohegans.

Opposing all three of these projects are two entities that have grown exponentially as a direct result of gambling money: the Grand Ronde tribe and the state-run Oregon Lottery. Both these players are under heavy pressure to keep the money flowing into programs such as tribal health care clinics and public schools, and the last thing they need in a faltering economy is new competition closer to the state’s dominant financial center. That’s a change that few in state government would welcome, with budget shortfalls already requiring huge spending cuts. Both Republican Chris Dudley and Democrat John Kitzhaber have declared their opposition to the Warm Springs deal, meaning the stakes are high for the tribe to make something happen quickly in Cascade Locks. Indeed, the stakes are high for all of the players vying to develop a casino close to Portland.

|

Supporters of a Cascade Locks casino, from left to right: Chuck Daughtry (Port of Cascade Locks), Chief of the Warm Springs Delvis Heath Sr., Chief of the Paiute Joe Moses, Scott Moses (tribal council member, Seekseequa district), Reuben Henry (tribal council member, Seekseequa), Smith, Pitt and Tim Lee (Port of Cascade Locks). // PHOTO BY ANTHONY PIDGEON |

It’s two hours by car from the Warm Springs Indian Reservation to Cascade Locks, but Pitt is adamant that his people have as much right to develop land here as anyone. For centuries their ancestors lived at the center of a river economy that revolved around the abundance of salmon. “We’ve always been here and we’ve never left,” Pitt says. “We were some of the richest people in the world on this river because of salmon. We ceded 10 million acres to the government and one of the things we got in return was off-reservation rights.”

The Warm Springs are one of four tribes with treaty fishing rights on the Columbia River, and while fishing hasn’t brought them much prosperity in recent years, it is increasingly valuable as salmon runs improve. But salmon money is nothing compared to the value of a casino next to a major interstate, a short drive from Portland. “This is the means for us to rebuild our economy, our way,” says Pitt. “People keep telling us what we should do with our land. They say ‘build a museum.’ Well we built a museum on the reservation. It was a loser. We’re not in business to go broke.”

Census figures show that there is no community in Oregon more in need of economic rebuilding than the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Per capita income on the reservation is less than half the national average. The college graduation rate is about one-fifth that of the rest of the nation. Nearly three times as many families live in poverty as in the rest of the country. The community has no local high school, saddling teenagers with a tedious daily bus ride to and from Madras that contributes to an already high dropout rate.

The numbers tell a different but similarly grim story in Cascade Locks. With more than 100 acres of vacant property in an industrial area once humming with timber jobs, the entire assessed value of the city adds up to $68 million, Seeger says. That results in just $168,000 per year in property taxes. “I can’t run a city on $168,000,” he says. Fortunately for him, the city also runs the utilities, which bring in enough revenue to keep the lights on — barely. The city can only afford to fund local police protection for 24 hours per week.

Pitt is only half-joking when he suggests that there should also be a fourth tribe under the Warm Springs banner in addition to the Warm Springs, the Wasco and the Paiute: the Cascade Locks. “It’s unbelievable how poorly these guys get treated in the Gorge,” he says. “They’re like second-class citizens, and we know all about that.”

Unlike other former timber towns, Cascade Locks has identified a way out of poverty. “We’re talking about 1,700 permanent jobs,” says Seeger. “That would triple our population. And this isn’t a project that’s going to be outsourced to India or China. The tribe is going to be here forever.”

After years of roadblocks, there’s a sense of momentum in Cascade Locks following the completion of the Final Environmental Impact Statement in August. A large sign in the center of town reads, “Welcome Warm Springs. Welcome jobs.” A carload of curious tourists pulls up as Pitt and Seeger tour the property and wishes them luck with getting the casino approved. On the business side, Pitt says the Warm Springs have entered into discussions with investors eager to back the project once it gets federal approval. Howard Arnett, a Bend attorney who has been representing the tribe since 1980, says, “I feel better about our chances than I have in a long time…We’ve cleared every hurdle.”

But more hurdles may lie ahead. Justin Martin, a Grand Ronde tribal member and lobbyist who is working to block the Cascade Locks deal, says the Warm Springs still have a long ways to go before building a new casino. “They’ve reached the end of the beginning of the process,” he says. “That’s it.”

|

An architect’s sketch of the proposed Cascade Locks casino, which would feature 2,000 slots, 70 gambling tables and a 250-room hotel just off I-84. // ILLUSTRATION COURTESY OF WALSCH BISHOP |

Justin Martin was 13 years old in 1983 when the Grand Ronde tribe won back recognition from the federal government after having been “terminated” as a federal tribe in 1954. He remembers his mother being jazzed about the news, but he had no premonition of how significantly it would alter his life and his community until he went in October 1995 to visit what he assumed was the tribe’s new bingo hall, only to be blown away by the magnitude of the Spirit Mountain Casino. In the 15 years since, Martin has earned an advanced degree from Harvard and built a powerful lobbying business in Salem, and the Grand Ronde have grown to more than 5,000 members who receive free health care, scholarships and even per capita annual payments from casino profits.

Tribes are not required to release detailed financial information to the public, but a recent report by two economists hired by Oregon tribes offers a window into a lucrative industry. Robert Whelan and Alec Josephson of ECONorthwest found that Oregon’s tribal casinos employed 5,614 people in 2008 and generated nearly $1.64 billion in economic output on revenues of $577.6 million.

Given that Spirit Mountain contains about a third of the tribal gaming machines statewide and is the closest casino to Portland, it’s safe to estimate that the Grand Ronde tribe earns about $200 million per year in net revenues at Spirit Mountain (total sales minus complimentary goods and services given away). Since setting up the casino the Grand Ronde tribe has earned more than $833 million in gaming profits (amount bet minus payouts).

But Martin is quick to point out that “12 or 13 years of economic success don’t come close to fixing the problems of the past 150 years.” True, unemployment and alcohol and drug addiction rates have improved among tribal members, he says. But they are still worse than the national averages. In addition, there’s no guarantee that the cash cow that has brought the tribe its recent prosperity will continue producing.

The Grand Ronde face increased competition from the state and constant demands to continue funding expensive tribal programs and to pay for a recent slew of ambitious upgrades at the casino. “Just like any other government we’re facing problems with how to fund our programs,” says Martin. “It’s been a challenge. We’re under pressure to pay off debts.”

Still, unlike other tribal casinos in more rural areas and larger players in the business, the Grand Ronde have not been forced to lay off workers. They employ 1,500 people at Spirit Mountain, and ubiquitous transit and billboard ads in Portland boast that the Spirit Mountain Community Fund has generated more than $50 million for worthy projects.

Bruce Studer, the Lake Oswego financier who came up with the idea for Oregon’s first non-tribal casino, is unimpressed with that figure. “They’ve done $50 million in their entire history,” he says. “We would do $150 million a year.”

|

Attorney Matt Rossman and financier Bruce Studer have partnered with a Las Vegas consultant and a Canadian finance firm on a plan to convert a former dog racing facility in Wood Village into a mega-resort they say would pull in an estimated $589 million per year in revenues. // PHOTO BY ANTHONY PIDGEON |

An architect’s sketch of the Wood Village Park casino resort, which would contain indoor and outdoor water parks, movie theaters, bowling alleys, a concert hall, a 290-room hotel, rooftop dining and 3500 slot machines, more than the major hotels in Las Vegas. // ILLUSTRATION COURTESY OF PETER WILDAY, ARCHITECT |

For a long time it was a mystery who was behind Studer’s ambitious plans for a Wood Village gaming and entertainment center. Studer and his partner, attorney Matt Rossman, first went public with their idea in 2005 without disclosing who their partners were. Now that they have made their way onto the November ballot with one of the two measures they hoped to pass, they are providing some jaw-dropping details about the size and scope of what they hope to build with the Las Vegas-based Navegante Group and the Toronto-based investment firm Clairvest.

Their plan calls for 3,500 slot machines (Spirit Mountain has fewer than 2,000), 150 gambling tables, a 290-room hotel, a concert hall, an indoor/outdoor water park with a flow wave machine for surfers, a 14-screen movie theater and 36 lanes of cosmic bowling. Clairvest, one of the investors in a recent casino development near Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, would finance the deal. Navegante, run by a former chairman of MGM, would design and manage the casino.

“The investment is there and the players are in place,” Studer says. “We’ve got the best team on the field.”

Studer says the resort would earn $589 million in annual revenues at full build-out, employing 5,000 people between construction jobs and permanent positions and contributing $150 million per year to public schools, counties and municipalities.

If those kinds of numbers were to come to fruition, one non-tribal casino in Wood Village would be earning more money than all nine tribal casinos in Oregon combined. It would also wreak havoc on the Oregon Lottery and the Grand Ronde’s Spirit Mountain. State analysts estimate it could take away $72 million to $79 million per year away from lottery proceeds. Martin predicts the Grand Ronde would have to lay off half of its 1,500 employees at Spirit Mountain if the Wood Village casino were to go through.

Studer and Rossman say their project would simply give consumers more choices. They describe it as the largest unsubsidized economic development project in the state, thousands of new jobs created with out-of-state capital. “Not one dime of taxpayer dollars will be used,” says Rossman.

But it’s unclear whether their casino would be legal. Studer and Rossman have been trying to change the state constitution to allow non-tribal gambling since first going public with their plans five years ago. They haven’t succeeded yet, and their latest attempt to put the question on the ballot didn’t get enough signatures.

Their legal position is now complicated because only one of the two measures they backed made the Nov. 2 ballot. Between the constitutional issue and limited support for the casino in polls, the odds seem against them — for now. They’ve said that they can move ahead without changing the constitution, but opponents such as Len Bergstein scoff at that notion.

Bergstein is the well-connected Portland-based public affairs strategist who helped the Grand Ronde build their casino and is now trying to help the Warm Springs build theirs. He says the constitutional issue is hardly a detail that Studer and Rossman can shrug off. “They spent $1.3 million to get two initiatives on the ballot, not one,” says Bergstein. “They knew they had to change the constitution. They failed. They did not get enough signatures. Now they say they don’t need it. Well, nobody believes that.”

It will be up to the courts to decide that issue and others if the Wood Village casino earns approval. Studer and Rossman say they fully expect a lawsuit from the tribes as they progress toward a non-tribal casino.

|

Grande Ronde tribal chairwoman Cheryle Kennedy at Spirit Mountain Casino, Oregon’s most successful casino. Spirit Mountain employs 1,500 people and funds tribal programs. // PHOTO BY ANTHONY PIDGEON |

Until recently, the player that seemed to have the best shot at building a mega-casino near Portland first was the Cowlitz tribe of Washington. Led by the charismatic David Barnett, son of the tribal chairman who led the Cowlitz to regain federal recognition in 2002, the Cowlitz entered into a partnership with the gambling-rich Mohegans of Connecticut, purchased land 30 minutes north of Portland in La Center, and gained a Final Environmental Impact Statement from the Bureau of Indian Affairs long before the Warm Springs did.

But the Cowlitz tribe has run into serious legal problems. A February 2009 U.S. Supreme Court ruling against the Narragansett tribe shot down that tribe’s attempt to take land into trust to form a reservation around a casino after regaining federal recognition. That is exactly what the Cowlitz are trying to do in La Center, so the precedent could prove a deal killer.

The Cowlitz also face a crisis in leadership after an auto accident involving the front-man Barnett and his girlfriend left him seriously injured in November 2009. The Vancouver Columbian later reported that Barnett and his girlfriend both allegedly suffered from cocaine addiction and had tested positive for drugs after the accident.

Cowlitz tribal chairman William Iyall says Barnett is recovering from his injuries and the casino project is very much alive despite the court decision, with “a steady dialogue” between the federal government and the tribe. “It took us 26 years to get federal recognition,” Iyall says. “Hopefully we’ll get a decision (on the trust land for the casino) sooner than that.”

But even if the federal government approves the trust land and the legal issues stemming from the Supreme Court decision are somehow resolved, the Cowlitz will still need to negotiate a compact with the state of Washington before breaking ground. Another challenge involves the once-mighty tribe investing in the deal, the Mohegans, who are struggling with debt and recently laid off 475 people at their Foxwoods Casino in Connecticut.

“We believe the Cowlitz casino is pretty much dead in the water,” says Mark Hohlt, rules and policies manager for the Oregon Lottery.

The wobbly foundation of the Cowlitz casino represents a huge relief for the player with the largest stake in stopping the migratory flow of gamblers from Oregon into Washington: the Oregon Lottery. The Lottery pulls in twice as much in gambling revenues as all nine tribal casinos combined. State government has grown increasingly dependent on this money to fund schools, economic development and parks. Since coming into existence in 1984, the lottery has steadily grown its offerings and today pulls in the bulk of its bounty from video poker and slots at restaurants and dive bars sprinkled around the state, most prevalent in the Portland area.

The lottery contributes more than a billion dollars each biennium to education, parks and selected economic development investments.

But lottery revenues are sliding as consumer confidence wanes and the job market remains weak. The smoking ban has also taken its toll on gambling in taverns. Overall, gamblers are spending less time at the machines and betting less, says lottery spokeswoman Mary Loftin. “Habits have changed,” she says. “It’s a tightening of the belt.”

Even as the trend toward a “new austerity” convinces recreational gamblers to keep their money in their wallets, the state is under pressure to continue pulling in more gambling money. The same pressure applies to everyone else in the game, including some of the most powerful players in Vegas, Atlantic City and tribal gambling. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that some of the richest tribes in the nation have been unable to pay off their debts to investors, resulting in tighter credit, tougher loan terms and higher interest rates. Oregon tribes saw their casino revenues drop by $20 million in 2008, and Portland economist Robert Whelan estimates they fell by another 7% to 8% in 2009. Oregon Lottery revenues dropped by $134 million in fiscal 2009.

If a more cautious approach to consumer spending proves to be the long-term trend it appears to be, the growth engine driving much of this would-be prosperity would not be the recreational gambler, who would be sitting out this round in the interest of fiscal responsibility, but rather the problem gambler, who is unable to stop playing due to addiction issues. That raises a large question: Are there really enough problem gamblers living in or passing through Oregon to undo 150 years of past wrongs to the tribes, to rescue a state budget from looming shortfalls, and to create the thousands of private sector jobs that businesses have been unable to generate during the downturn?

It seems unlikely. But don’t expect Pitt and Seeger and their allies on and off the Warm Springs Reservation to fold their cards any time soon. The same goes for Studer and Rossman and their high-powered backers, and even the Cowlitz and the Mohegans. The pot isn’t as sweet as it used to be, and the odds are as long as they’ve ever been, but every gambler knows that you have to play to win.

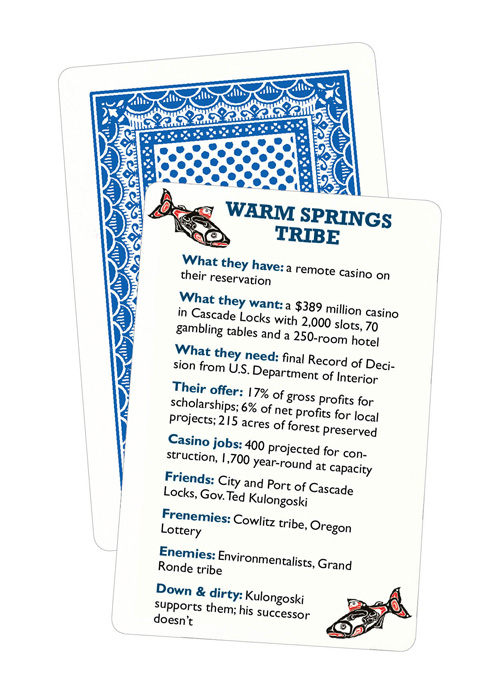

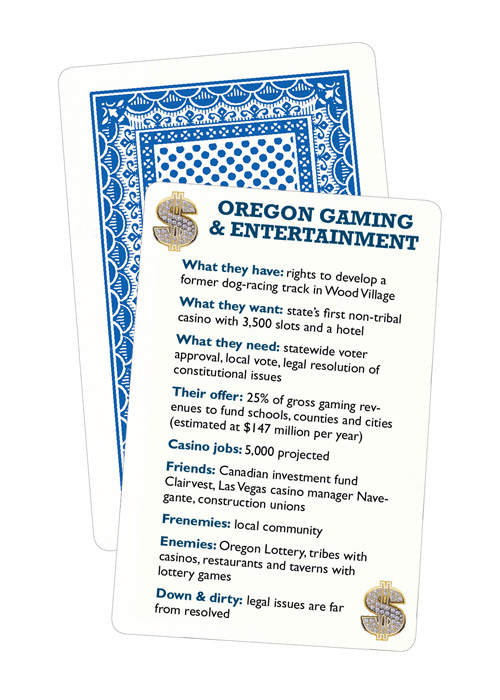

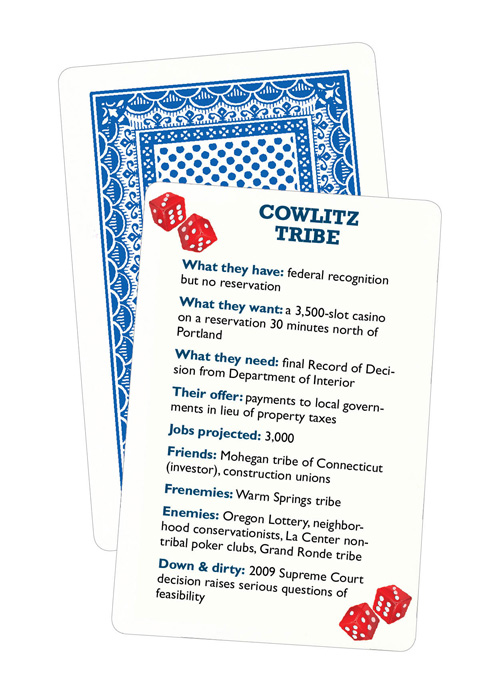

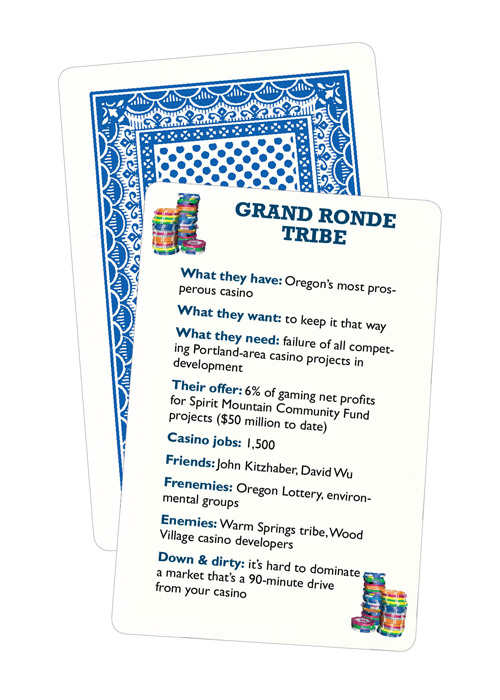

The Players

Who’s at the table, what they’re holding, what they need and what they want

|

|

|

|

|