On a cold, early-winter afternoon, about 25 of Redmond’s economic players are gathered in a tiny downtown church hoping for a glimpse of their future.

On a cold, early-winter afternoon, about 25 of Redmond’s economic players are gathered in a tiny downtown church hoping for a glimpse of their future.

Bend in the Road

Fast-growing Redmond doesn’t want to become another expensive city that drives out its workforce. At a critical juncture in its history, it searches for the right identity.

By Abraham Hyatt

On a cold, early-winter afternoon, about 25 of Redmond’s economic players are gathered in a tiny downtown church hoping for a glimpse of their future. The first major storm of the winter blew through Central Oregon a few days before. They hold jackets under their arms as they, along with Mayor Alan Unger and other city staff, cluster around a half-dozen easels where maps show a potential downtown revitalization plan.

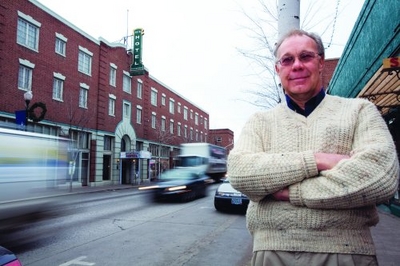

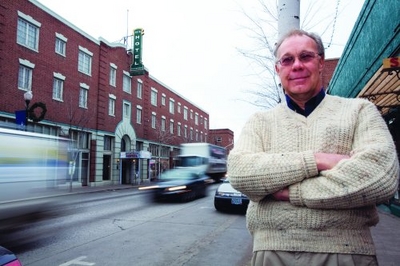

Photo by Simone Paddock Photo by Simone PaddockRedmond Mayor Alan Unger makes a stand on traffic-heavy Sixth Street. Both Fifth and Sixth streets will become city property when Highway 97 is diverted around Redmond, and the community is trying to figure out how to turn the current highway business district into a real downtown. |

Colors and lines fill city blocks. Blue is a new city hall with an accompanying park or plaza. Orange is an entertainment complex next to a big park. Red turns several blocks of one major street, currently the southbound arm of Highway 97, into what’s called a festival street: wide sidewalks, narrow driving lanes, water fountains, trees, public art.

A Redmond native, Unger is a convivial man with a wry grin. He’s spent the last five years as mayor grappling with the beginnings of an economic boom spurred by growth in Bend, 15 miles to the south.

That growth has been an alarm clock of sorts for Redmond. In the last few years, the city has undergone a fairy tale-like change — a sleepy town awakened by Central Oregon’s economic expansion. Like Rip Van Winkle himself, Redmond — which now bills itself as the state’s fastest-growing city — seems alternately amazed and concerned about what the future has to offer.

But unlike with fairly tale characters, waking up is only the beginning of Redmond’s story. The city must deal with a host of growth-related issues: housing, schools, traffic. It’s also been pushed into the tricky realm of creating an identity for a place that has never had one. The biggest influence is Bend, the glamorous big sister that Redmond will either follow or leave behind as it forges its own path.

TO CREATE THAT POTENTIAL DOWNTOWN PLAN, engineers from Sera Architects, a Portland firm hired by the city, have taken over the interior of a 95-year-old church. The building usually serves as a community center; its folding chairs have been stacked against walls to make room for tables covered with laptops, paper and maps.

The engineers have been there for a day and a half. There’s a slight feeling of urgency in the air, and for good reason: By late 2008, the Oregon Department of Transportation hopes to be finished with an estimated $88 million bypass project that will divert Highway 97 around Redmond. When it opens, Fifth and Sixth streets, the city-bisecting, two-lane roads the highway currently occupies, suddenly will become city property. By that time, officials must be ready to jump on their once-in-a-city-lifetime opportunity to turn a highway business district into a downtown.

Matthew Arnold, an associate with Sera, challenges the group of business owners, developers and city staff to ask themselves what the purpose of their new downtown should be. “Is moving traffic your goal or creating a pedestrian- and retail-friendly place?” he asks. They pepper him with questions: But how will people get from the north end of the town to the south? What side streets will be forced to take that increase in traffic? At one point, Unger jumps in. Not so much addressing the engineer as the crowd, he agrees that the city needs to look at bold ideas. “And then we need to look at what’s realistic,” he says.

|

AFTER THE MEETING, UNGER WALKS two short blocks to City Hall to check his mail. His breath frosts in the cold air. He seems unfazed by the critical response to the Sixth Street redevelopment idea. This is the third project the city and Sera Architects have collaborated on. Unger says any problems will be worked out in the next month.

Sitting in his own office in the cramped City Hall, city manager Michael Patterson says one problem with the Sixth Street concept is that it’s too much like Bend. That’s an accusation made by several people concerned about the plan. What do they define as “Bend”? Some point to a high cost of living or an abundance of high-end boutiques and condos. Sometimes Bend is explained simply with a dismissive wave to the south. For Patterson, Bend represents an economic climate in which working-class families can’t survive.

But not everyone hates the idea of Bend. A few blocks away on Sixth Street — and at the heart of the redevelopment plan — sits Santiago’s Mate Company. “I’d wish they’d Bend-ify a little,” owner Nathaniel Winkler says of Redmond. “You can’t have a walking-friendly downtown with all this traffic.”

The café sells yerba mate, a specialty tea familiar to many in places such as Bend, but not as popular in Redmond. Winkler says only 20% of his business is retail based; his primary focus is online wholesale. On the afternoon the downtown plan is presented, the brightly lighted café is empty. Containers of the aromatic herb line the walls. A steady stream of the estimated 33,000 cars and trucks that currently use Sixth Street each day roar and bang past outside.

Despite what he hopes downtown will become, Winkler chose his location because it wasn’t Bend. In other words, it was affordable. Bud Prince, manager of Redmond Economic Development, says the city’s boom is due in part to that very thing. It helps, he says, that the city is home to the regional airport, and is a center point for Central Oregon’s three major counties (and five resorts being built in the region). But more than anything, it has cheap land and a low cost of living.

DRIVING THROUGH REDMOND’S NEIGHBORHOODS yields no surprises about the small city. There’s a high-desert sparseness here. Simple, sometimes run-down working class homes line streets near the railroads on the east side of town. On the west side, land that sold for $30,000 an acre 10 years ago now sells for $300,000 an acre. New homes look like they’ve popped up through the soil.

Patterson says one of the biggest problems the city faces is affordable housing, a dilemma tied to its exponential population growth. Fifteen years ago, 7,200 people lived in the city. Today newcomers outnumber old-timers — those who lived in Redmond before 2000 — two to one. And the marketing group Economic Development for Central Oregon thinks the city’s current population, 21,000, will grow to 47,200 by 2025 — a 125% jump.

A lack of affordable housing will drive Redmond’s workforce into even smaller towns such as Prineville or Madras, new satellite cities around a new economic supernova. That may already be happening. But Patterson said the city can keep future housing costs down by avoiding a Bend-like atmosphere where there’s a lot of downtown condos, which can have a ripple effect on property values through the city. “If we have too many high-end condos, we’re lost,” he says.

An equally pressing problem is the city’s school shortage. Nearly 2,100 students pack into the city’s only high school every day. This year voters approved a bond that would pay for a new elementary and junior high school. However, voters shot down a previous high school building bond, and city officials are unsure if another attempt would be successful. Unger shakes his head as he talks about the money the school district will have to raise in the next 50 years. His eyes are serious behind his glasses when asked for a figure. “$300 million,” he says, his voice rising as if he’s asking a question.

A FEW HOURS AFTER THE ENGINEER’S MEETING with economic leaders, the sun sets on a 61-acre lot about two miles east of the church. Rabbits scurry in the twilight through brittle, thigh-high weeds. The land is currently home to a few pine trees, two junked cars and a gutted ambulance. It’s also one more component in Redmond’s jigsaw-puzzle economic future. By this summer, Bend-based Edge Development Group hopes to have city approval for a $15 million, 28-lot industrial complex.

Redmond is trying to keep up with its growth. Last year it expanded its urban growth boundary by 2,200 acres, and made plans to expand by another 5,600 acres within 50 years. There’s a new community center in the works. The city council plans to make a final decision on what the downtown redevelopment plan will look like sometime this month. Pending that decision, the city hopes to break ground on a new city hall and parking project before the end of the year.

As Unger says, “If you grow fast, you have to react fast.”

But can the city avoid becoming what it fears? Economists say that for every destination town such as Bend there is often a Redmond — a nearby city where land and housing are cheaper, where industrial parks far outnumber the few, if any, boutique retail stores. They dot the western United States, these cities caught up in the gale-force economic growth fueled by their booming neighbors.

Ask Redmond’s business owners, developers and civic leaders about how to steer that growth and their conversations are infused with excitement and uncertainty. They use the phrase “vibrant downtown” often. But no one has concrete answers as to how to create the identity that they say the growth must be built on.

There is only an energy in their voices that reveals they know how urgent it is for them to find an answer, how urgent it is for them to determine, right now, what comes next for the city of Redmond.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]