Employers grapple with increased drug use on the job while facing a worker shortage. Tougher policies could help — or hurt.

THE FIX

Employers grapple with increased drug use on the job while facing a worker shortage. Tougher policies could help — or hurt.

Story by Oakley Brooks

Photos by Jon Meyers

A few years ago, a former production-line worker returned to Roseburg Forest Products looking for a job. He was a likable guy and had been a solid performer. “The kind of person you want on your team,” says RFP’s HR director, Jon McAmis. But five years earlier he had burned through RFP’s drug-abuse program, first failing a urinalysis as part of the company’s random sweeps of its workforce, then failing to test clean following the treatment program he underwent during a probation period.

“He sat down in front of me and even teared up a little and told me this was an important thing for him,” McAmis says. “We had other people we could have hired. But from a business perspective, we already had invested money training him. And people were recommending him, saying he’d really changed.”

McAmis rehired the man, giving him a rare third chance. Six months later, the employee tested positive for marijuana and again was shown the door. “That one stung,” says McAmis.

Across the state employers are struggling with two devilish phenomena: Their pool of skilled workers is steadily shrinking and that group is increasingly riddled with drugs. The United States is looking at a worker shortage of between 4 million and 10 million over the next decade. At the same time, drug use in Oregon is robust (see statistics on following pages). And that’s showing up glaringly in workplaces. At the thousands of companies served by the private drug-tester Oregon Medical Labs, 6.3% of all employees and job applicants tested positive for drugs in 2005, up from 5.3% in 2004. (The state does not keep statistics on workplace drug use or related accidents.) One national study shows workers on drugs are more than three times more likely than sober colleagues to be involved in an accident.

In theory, Oregon employers face two choices: Look the other way and hope to minimize lost time, thefts and bad accidents, or crack down and purge drugs from the workplace, hoping not to lose too much skill and sheer manpower in the process.

“We continue to get a wave of positive tests… “We continue to get a wave of positive tests…We’ve kind of tried the tough-love approach so far. But our system today is enabling people on drugs.” — Jon McAmis, Roseburg Forest Products |

In reality, most Oregon employers oscillate between those extremes, coaxing employees into treatment, taking a second chance on older, skilled people, ignoring the whiff of marijuana or some glazed eyeballs now and then. They even pursue pricey drug testing for new applicants to send a message that they are entering a “drug-free” workplace — something few Oregon companies unequivocally can claim.

Stories of slowed expansion are becoming more common as businesses struggle to find workers who can pass a drug test — Georgia Pacific in Burns and Barrett Business Services in Newport are two examples. Equally alarming may be the companies large and small around the state that say, openly or in hushed tones, that they would never test their current workforce because their business would be stopped cold.

“If we were talking about a virus, we’d have to call it an epidemic,” says Dan Harmon, Hoffman Construction’s executive VP and general counsel.

THE FIX FOR DRUGS IN THE WORKPLACE, proposed by an Oregon Business Plan panel a year ago and backed by a current legislative work group chaired by Harmon, is to massively increase the number of businesses that have a comprehensive drug policy. That policy, in line with federal workplace standards, would include regular drug testing, addiction treatment and thorough enforcement and promotion by supervisors and company executives. Harmon’s group also is proposing incentives for businesses to adopt a drug policy; other legislators plan a bill requiring drug testing for people receiving unemployment payments to keep the pipeline for new workers clean.

Experts in the legislative group suggest that Oregon’s workplace drug problem could be solved if a strong majority of businesses and the state send the message that one must be drug-free to enter the workforce.

“I’ve empathized with workers on marijuana coming off a weekend. We’ve had some damn good employees who have used marijuana and functioned well in their jobs.” |

“If all employers had the same standards, we’d have a lot smaller problem with drugs,” says Jerry Gjesvold, employment services manager for Eugene-based drug treatment provider Serenity Lane and a member of the legislative work group.

Currently, only 13% of businesses statewide have anything like a best-practices policy in place. The Oregon Business Council and state health officials have suggested boosting the portion of Oregon companies with drug-free policies to 75%; the business plan has begun a pilot program with local chambers to get employers around the state on board.

Statewide advocates acknowledge their targets are ambitious; the policy they are pushing also has gotten mixed reviews from companies such as RFP, which has had a similar policy in place for almost 20 years.

“We continue to get a wave of positive tests and failures on people who go through treatments as part of their last-chance agreement,” McAmis says. “We’ve tried the tough-love approach. But our system today is enabling people on drugs.”

And whatever promise there is in the cumulative effect of many employers vowing to be drug free, individual employers have to find their way out of their current fix: How do they start cleaning up their workforce and not lose it at the same time?

BOTH HOFFMAN CONSTRUCTION AND RFP PUT THEIR POLICIES TO WORK in the late 1980s as the federal government attempted to crack down on drug use at its contractors. This was the period when the Exxon Valdez ran aground in Alaska, and its captain was charged, but acquitted, with being drunk. A Conrail freight train also rammed into an Amtrak passenger train in Maryland, after which the Conrail conductor admitted smoking marijuana. Rigorous testing began in transportation industries. Subsequent laws required any company doing business with the federal government to enforce a drug-free workplace; employers risked a five-year moratorium on federal contracts if drugs were involved in a company accident. OSHA laws also have required that workers be “unimpaired” at work.

Hoffman’s Dan Harmon says his company’s pre-employment drug testing failure rate — initially as high as 18% — has gone down since the late 1980s. But company policies have failed to halt drug use at the company. After employees and subcontractors attend treatment and fail a second drug test, they’re permanently banned from Hoffman’s job sites. In 20 years, the company has banned nearly 1,000 workers; in the last 10 years alone, it has had 20,000 failed drug tests (pre-employment screens included) and 250 accidents attributed to drug and alcohol use.

Hoffman has been involved in some of the more high-profile developments in Oregon — the latest is Portland’s South Waterfront — but Harmon worries that the company’s future may be endangered by its shrunken worker pool.

“If it continues to shrink it’s going to be a barrier to us and others looking to expand,” Harmon says.

In RFP’s mills, where about half of 4,000 Oregon employees belong to a union, a “last- chance” program similar to Hoffman’s has been protected in contract bargaining since 1989. McAmis says bluntly that drug users have viewed the last chance not as a desperate measure but as a “get-out-of-jail-free card” to avoid being fired. Lumber and Sawmill Workers union shop president Cindy Black agrees that the policy isn’t working — nor is random testing, which fails to sweep through enough of Roseburg’s workers in a given year. “There are a lot of people here on drugs that just haven’t been caught yet,” Black says, noting that her unit at RFP’s Riddle plant has never been randomly tested in the 17 years she’s been there. “We’re fortunate we haven’t had some fatalities.”

“There are a lot of people here on drugs that just haven’t been caught yet. We’re fortunate we haven’t had some fatalities.” “There are a lot of people here on drugs that just haven’t been caught yet. We’re fortunate we haven’t had some fatalities.”— Cindy Black, Union shop president, Roseburg Forest Products |

The recent methamphetamine crisis only has compounded drug problems in Oregon workplaces. Though the rate of positive tests for meth in the workplace has leveled off (something drug experts attribute to new Oregon laws barring the cold medicine — and raw meth ingredient — pseudoephedrine), for several years it surpassed marijuana as the most common drug in employee tests. And heavy users’ sore-covered faces, rotting teeth and erratic, aggressive behavior have been hard for employers to ignore.

“Fifteen or 20 years ago you could use drugs for a while and it wouldn’t become that problematic,” say Gjesvold. “But meth is a different story. It’s nasty and it moves quickly and creates some dangerous situations.”

IN DOUGLAS COUNTY, WHERE EMPLOYERS’ recent complaints about drug use have been higher than the rest of Oregon, RFP’s fellow wood products companies have taken divergent approaches to addressing the issue.

At C&D Lumber, a sawmill and planing mill in Riddle, general manager Brad Hatley has a zero-tolerance program. “If you fail a drug test, you’re gone,” says Hatley, who says he will let employees elect treatment if they come forward before a test and admit they would fail. The failure rate in pre-employment testing has fallen to about 1% over the past two years.

Percentage of Oregonians using illegal drugs in the past year | |

| Marijuana and hashish | 14.0% 415,000 |

| Pain relievers | 6.0% 29,000 |

| Hallucinogens | 2.5% 74,000 |

| Cocaine | 2.0% 60,000 |

| Methamphetamine | 1.1% 31,000 |

| Ecstasy | 1.0% 29,000 |

| SOURCE: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration study 2003-2004 | |

C&D might be considered a success story, except that Mimi Bushman, who runs the state-funded Workdrugfree advocacy program, worries that a harsh policy simply sends an addict to the end of the unemployment line, where he has no opportunity for treatment. “It just recycles the problem and it’s one of the reasons you have those high pre-employment positive drug tests elsewhere,” Bushman says.

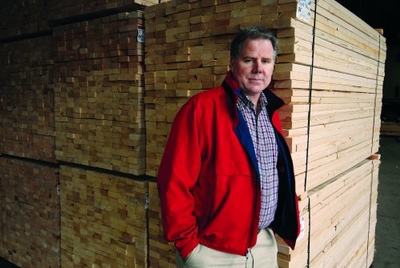

In the northern part of Douglas County is Murphy Plywood, which until recently ran a mill in Sutherlin. Several Douglas County residents mentioned the company when asked about some of the more relaxed drug policies in the area. When his company’s reputation was presented to him, Murphy Plywood president John Murphy understandably bristled. “For every person who thinks we’re lax, I’ll show you 10 who say we have a clean workplace,” Murphy says.

Murphy, however, described his own policy toward those who test positive once for marijuana as “lenient.” That worker is allowed to return to the workplace as soon as he or she can produce a clean urinalysis. (The worker is let go if he can’t get clean in 30 days.) Murphy says that person also will likely be taken off jobs involving moving machinery and put under close supervison. If other substances such as meth or cocaine are detected in a drug test, a worker is sent to a treatment program before returning to the job. Any positive drug test, regardless of the substance, puts Murphy workers into a last-chance agreement, and John Murphy says they are let go on subsequent offenses.

Speaking from his current office in Eugene (the Sutherlin mill burned down in July 2005 after a fire broke out in a dryer motor), Murphy says he and his human resources staff arrived at their approach to marijuana because “I’ve empathized with workers on marijuana coming off a weekend.” The policy also allowed him to accommodate employees who have had a good work record. “We’ve had some damn good employees who have used marijuana and functioned well in their jobs,” he says. Greg Gassner, Murphy’s HR director, adds, “If it’s a post-accident test and it’s a low level [of marijuana] and it hasn’t affected his performance, we give him a chance to get clean.”

IT WOULD BE HARD FOR MANY EMPLOYERS IN OREGON to argue with Murphy’s policy. Jerry Gjesvold says at least one large employer he knows — a well-known name but Gjesvold asked it be kept confidential — has said it would never randomly drug-test because it would sweep up too many good workers.

Some small-business owners, already averse to the cost and hassle of a drug program, say they don’t want to deal with the consequences of a scientific drug test. In Brookings, Lesa Cooper runs a 12-person concrete construction company with her husband, Gary, and has had a miserable time dealing with drug addicts.

She’s been physically and verbally attacked when confronting suspected meth addicts, withstood several robbery attempts and frequently absent workers, and even moved her family to a remote location to avoid incidents with former employees.

With less-troublesome drug users who are skilled, show up semi-regularly and don’t show violent behavior, she’s more lenient. “I don’t want to lose the guys I like to work with who every now and then screw up,” says Cooper. “Some [other contractor] will pick them up in a heartbeat. You’d like to do everything the way you’re supposed to. But it’s become ‘If it isn’t happening on my jobsite, I’m going to look the other way.’ And you do put up with some lost time.”

Percentage of workers using illegal drugs in the past month | Percentage using illegal drugs other than marijuana | |

| 9.5% | Oregon | 3.7% |

| 8.1% | United States | 3.6% |

| SOURCE: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration study 2003-2004 | ||

Gjesvold says leaving room to negotiate with drug users is “selfish” of employers, but he understands why they do it. “They’re hard up,” he says. “The higher the skill level, the tougher people are to find.”

Gjesvold says it may take another accident on the level of Exxon Valdez to spur the business community and state leaders into widespread action on drugs. He notes that it wasn’t until meth had ravaged the general population that legislators and the governor passed the law banning pseudoephedrine. “You’re going to see some bizarre things and employers are going to suffer in terms of ROI,” says Gjesvold. “I hope I’m wrong.”

Oregon’s legislative work group is hoping some carrots for

businesses may swing the majority toward addressing drug abuse in their workplaces.

They are proposing that em-ployers with a comprehensive drug policy get immunity from lawsuits brought by employees fired for drug use, and that employers with approved policies get a discount on workers’ comp rates. A similar workers’ comp program in the state of Washington was associated with a reduction in workplace accidents between 1994 and 2000.

The Oregon group also has discussed setting up a fund to pay for drug treatment of employees at small businesses. A 2005 “mental health parity” bill calls on insurance providers to cover in-patient drug treatment. But just 60% of Oregon businesses provide health insurance; for the uninsured, in-patient treatment starts at around $5,000.

The work group would also like to rein in Oregon’s medical marijuana law by limiting the prevalence of possession cards and the legal amounts cardholders can possess. There are now more than 19,000 marijuana possession cards in Oregon for users and caretakers, which allows users to possess up to 24 ounces of marijuana.

That puts employers trying to reduce drug use at a further disadvantage, as does the fact that Oregon courts still haven’t decided if companies need to accommodate workers with a medical marijuana prescription.

What may be hopeful for employers tearing their hair out over the drug issue is the emerging advocacy of employees in some workplaces. It was an employee survey two years ago that led Brad Hatley to strengthen the drug policy at C&D Lumber. “They were telling me that our policy had too many loopholes and it needed more teeth,” he says.

At Roseburg Forest Products, shop president Cindy Black appears ready to lead a similar effort. She says she’d be open to a stricter policy: One failed drug test and you’re out. “It’s a drug-free workplace and it’s clearly stated,” she says. “New people coming on shouldn’t have that second chance. The company would be protecting itself, for sure, but they’d also be protecting us. The last thing I want to do is pull someone out of a piece of machinery.”

Some employers admit they need all the help they can get. Says RFP’s Jon McAmis: “We’re really at a loss as to what to do next.”

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]