You’ve always had to have big ideas. Right now you have to have a very, very big idea.” — JAY EISENLOHR, AMBRIC

You’ve always had to have big ideas. Right now you have to have a very, very big idea.” — JAY EISENLOHR, AMBRIC

“It’s a very difficult environment. You’ve always had to have big ideas. Right now you have to have a very, very big idea.” — JAY EISENLOHR, AMBRIC

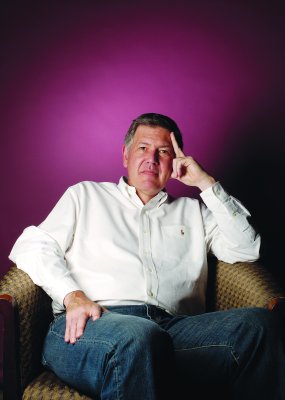

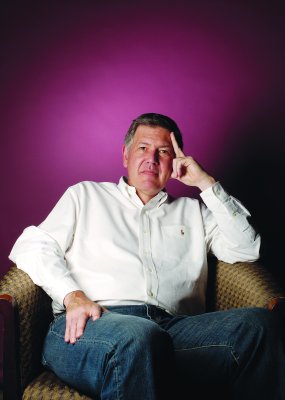

Jay Eisenlohr, Ambric Photo by Michael G. Halle |

BY CHRISTINA WILLIAMS

Jay Eisenlohr figures he’s got a shot at the whole megillah this time and with two previous startups under his belt, he has a base of experience to speak from.

“This is the first company that I’ve started that has the potential to do an IPO and stand alone,” he says. “It has the potential for thousands of people and a campus.”

It’s a lofty goal for a 60-person startup that’s going up against the biggest names in the semiconductor industry. Of course, Eisenlohr also will acknowledge that the chance that Beaverton-based Ambric will even be alive in five years is no better than one in 10.

Nodding in agreement is Christian Prusia, the founder of Enuclia, a semiconductor company that aimed at the digital display market from its Beaverton headquarters, but fell short of the goal.

Enuclia dropped behind on its production schedule and was forced to close this summer when one of its key investors balked, spooking the others. With no money to finish its first product, there was no other choice but to pull the plug.

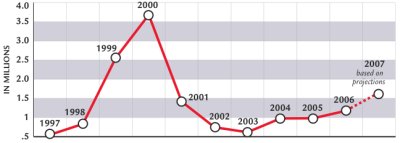

When Enuclia went down, it prompted some to declare the region’s storied display cluster all but dead. After all, projector company InFocus has gone through multiple layoffs and is up for sale by the board, Pixelworks has dramatically scaled back its operations and founding CEO Alan Alley left the business to work in the governor’s office. Even Planar Systems, the sector’s stalwart that acquired Clarity Visual Systems last year, has missed revenue targets and watched its stock price slump.

“[Enuclia] was the last great hope for the video processing silicon sector here in Portland,” says Eric Rosenfeld, managing partner at Portland-based Capybara Ventures, a seed investor in Enuclia. “They were so close with so many of their customers.”

Rosenfeld is quick to say Enuclia’s fall doesn’t signal a looming clear cut of Silicon Forest, but the thinning does point out some of the region’s oft-mentioned competitive disadvantages, namely: the lack of a research-oriented university, the lack of experienced high-tech managers, the lack of a critical mass of companies that attracts said managers, the lack of high-tech investors and the lack of je ne sais quoi — the rabid drive for success that is present in other high-tech meccas with a 24/7 work culture. That’s absent, many say, in Oregon where warm summer days and ready access to the great outdoors sometimes eclipse the desire to stay inside and pound out code under the fluorescent lights.

Yet it may be too soon to recite the epitaph for Silicon Forest. For all the well-known shortcomings, there are still strengths. It’s home to the world’s largest concentration of Intel employees, and the fact that Intel cut just over 1,000 jobs last year is good news for the startup world as top-trained talent becomes available. And even before Intel was a force, there was Tektronix, and Tektronix begat Mentor Graphics begat Planar begat InFocus begat Pixelworks and Enuclia. Silicon Forest talent runs deep.

Yet it may be too soon to recite the epitaph for Silicon Forest. For all the well-known shortcomings, there are still strengths. It’s home to the world’s largest concentration of Intel employees, and the fact that Intel cut just over 1,000 jobs last year is good news for the startup world as top-trained talent becomes available. And even before Intel was a force, there was Tektronix, and Tektronix begat Mentor Graphics begat Planar begat InFocus begat Pixelworks and Enuclia. Silicon Forest talent runs deep.

And, with Ambric as exhibit A, the startup drive hasn’t diminished. By the end of the year Ambric, with Intel alum Howard Bubb as its CEO, will be in production on a chip that makes it easy to synchronize multiple computers. It has applications for high-end video and medical imaging, among others. Ambric has raised just south of $20 million in venture capital from OVP Venture Partners and others. Eisenlohr says the company will raise more before the year is out and will hire more engineers and programmers as it expands to other markets.

Finding the people is the least of his worries. As Eisenlohr puts it: “This is one of the truly ripe places for raw talent.”

ALAS, TALENT ISN’T ALL IT TAKES. Even the triple threat of talent, money and a killer technology wasn’t enough for Enuclia, which raised $18 million from top-shelf VCs who wouldn’t have placed a bet without the chance at a hearty payoff.

Prusia attributes Enculia’s failure to a lack of two things: speed and communication.

“Any company in Oregon is going to face this: How do you innovate locally and efficiently tap into your customers who are in Asia?” Prusia says.

Enuclia was developing a chip to be used in high-end televisions, which are universally manufactured overseas. And in addition to being far away, the TV-makers are updating their technology at an ever more rapid clip. “It used to be a 18-month design cycle. It’s nine months now. At the end of the day it all comes down to that speed issue.”

In addition to keeping close counsel with customers, Prusia also learned too late that it’s imperative to nip hairy interpersonal issues right away. “If a team’s not firing on all cylinders it’s not going to execute,” he says.

But Gary Feather, VP, consumer systems and technology at Sharp Laboratories of America in Camas, Wash., cautions that one should view the stumbles of companies like Enuclia, Pixelworks and InFocus, in context with the wider market, one that’s getting tougher by the day as high-end digital displays become more of a commodity.

“As the prices decline and the competition grows, margins decline,” says Feather. “As the commoditization emerges and the barriers to enter decline, business gets tougher no matter where a company is located.”

Feather makes the differentiation between companies that have leading technologies and those that are leading markets, the latter being the more difficult maneuver to pull off.

“It’s great to have the first initial idea,” Feather says. “We have great people to do that. The sustainable execution is more difficult.”

Still, market-leading companies, such as Intel, are seeing talent here and staking their claim on it. In the last year, Santa Clara, Calif.-based Nvidia, a leader in graphics processing chips, doubled the size of its design presence in Oregon in part because last summer it had the chance to hire a talented development team en masse. The reason? The team’s startup failed and they were on the market.

|

Stexar, formed by a tribe of former Intel engineers in 2005, toiled in secrecy for about a year before folding. Jonah Alben, vice president of engineering for Nvidia, says his company jumped at the chance to hire a talented team and is still adding to its 65-employee Beaverton-based design shop. “We’re finding good people to hire,” Alben says. “It’s the right thing to do. We can’t just say we are a Silicon Valley company, we have to go where the great talent is.”

One could make the argument that, despite their ultimate failure, the fact that companies like Enuclia and Stexar are able to get off the ground and hire a great team in the first place is illustrative of the region’s strength. Prusia says everyone from his team who wanted to stay in Oregon has found another job — either with employers such as Nvidia or with less established companies.

“Those who wanted a job here have found one,” Prusia says. “Depending on their desire for risk, some even went to another startup.”

APPARENTLY THERE ARE PLENTY of risk junkies in Silicon Forest. In addition to Ambric, there are a handful of other display-related silicon startups getting ready to elbow their way into the market and try their luck.

“Consumers will see our product in 2008,” says Patrick Hauke, CEO and founder of Hillsboro-based Audio Mojo.

Hauke, one of Intel’s first Oregon employees in the ’70s, assembled a team of close to 30 people and developed a silicon-based wireless audio system for high-end digital television setups. Hauke says he’s had good luck finding people — he hired his entire marketing team from Pixelworks — but less luck with funding. “I am greatly disappointed in Oregon’s ability to fund startups,” says Hauke, who traversed both coasts talking to investors.

Avnera, a secretive Beaverton semiconductor company led by Manpreet Khaira, the founder of Mobillian (which sold to Intel in 2003), has lined up an impressive list of investors including Intel Capital, Bessemer Venture Partners and Best Buy. Rumored to also be making a play on the audio side of the business, 2-year-old Avnera is making a formal launch later this month.

Capybara’s Rosenfeld compares Avnera to Enuclia — a company with great potential to grow quickly once its chips are designed into products. “It’s the kind of company, a fabless semiconductor company, that is well-suited to Oregon,” Rosenfeld says. Capybara made a small ($100,000) investment in Avnera’s most recent round of funding.

All of these startups face the same stakes: One misstep is all it takes to fall flat in this market. But optimism runs high at this stage.

“We want to restore the luster to the cluster,” chants Sam Blackman, the 31-year-old CEO of Elemental Technologies, an eight-person startup in Portland started by former Pixelworks engineers.

Blackman is busily lining up customers for Elemental’s software, which runs on standard computer components but can handle high-volume video, appealing to professional users who want to save money as well as regular folk who want more sophisticated tools. “We’re getting a lot of interest,” Blackman says. “And once we have customers lined up we’ll have a better story to tell investors.”

As with any startup, investors will judge Elemental on the basis of its product and the potential for customers. But once the bets are placed, the odds say that many will fail.

“It’s a very difficult environment,” says Ambric’s Eisenlohr. “You’ve always had to have big ideas. Right now you have to have a very, very big idea.”

But perhaps the silver lining for the region is just this: It’s tough everywhere. And in Silicon Forest, there’s still room to put down roots — and, eventually, maybe even thrive.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]