By the time Scott Gephart moved from California to Oregon, he had become an expert in profiting from declining real estate markets.

THE PARTY’S OVER

THE PARTY’S OVER

The housing downturn hits Oregon’s financial, construction and real estate industries. Jobs fall, defaults rise and everyone worries over how deep it will go.

By Ben Jacklet

By the time Scott Gephart moved from California to Oregon, he had become an expert in profiting from declining real estate markets. He founded Chaparral Realty Group in Medford last August, and within six months he had built his business from three to 12 employees and leased a new 2,600-square-foot office.

“I think we’re the only growing company in our market,” says Gephart. “Everyone else is either shrinking or going out of business.”

The key to Chaparral’s growth has been the short sale, a complex deal in which a home is sold for less than is owed on its mortgages and lenders agree to accept a loss rather than repossess the property. Gephart’s expertise has served him well in Medford, where median home sales prices have dipped 13% over the past year. In one recent deal, Gephart sold a client’s home for $260,000 even though the property carried $330,000 in debt with three lenders. “With the market falling the way it is, short sales are where the action is,” says Gephart.

|

A year ago, short sales made up just a sliver of the Oregon housing market. Now they’re becoming increasingly common, according to industry experts. Title companies do not track them specifically, but insiders say short sales are growing more prevalent from Happy Valley to Medford and are approaching 50% of all closings in Deschutes County, where real estate offices get phone calls daily from would-be sellers who owe more on their homes than they are worth. Says Steve Brown, director of operations for the Portland office of First American Title: “I’ve been in the business since the late ’70s, and I’ve never seen so many short sales go through. They are a bigger factor than ever before.”

When the hottest real estate transaction is a money loser for lenders, there is a problem. Over the past year, Oregonians have taken pride in how well the state’s economy and housing market have withstood the national mortgage meltdown and the global credit crunch. But Oregon is not sheltered from the housing storm any more than it is immune to the forces of supply and demand, or gravity.

In 2007, real estate markets in Central and Southern Oregon were the first to fall. Now home values in the large metro regions of the Willamette Valley have dropped. Metro Portland, the state’s largest market, held up honorably for a while, but it could not stand alone. On March 25, the first cracks in the armor appeared: Standard & Poor’s Case-Schiller index found that Portland home prices had dropped .5% from January 2007 to January 2008, Portland’s first year-over-year decline since the index was created in 1987. If the trends from other U.S. cities are any indication of what is to come, the Portland market will almost certainly get worse before it gets better, because once home values begin to fall buyers become scarce and sellers grow desperate, resulting in a spiral of oversupply and stagnation.

Mark McMullen, a senior economist for Moody’s Economy who tracks Oregon, predicts it will be about five years until Portland’s median home prices return to their summer 2007 peak levels. “The correction will only be 10% or 12%,” says McMullen, “but we will be seeing some pretty lackluster gains following that.”

|

Portland’s home prices did not spike as extremely as markets such as Miami or San Diego, but they rose higher from their 2000 levels than cities such as Minneapolis, Chicago, and Boston. Housing markets in these other cities peaked and began correcting downward in 2005 and 2006, while Portland’s home prices did not peak until August 2007 and have remained flat since.

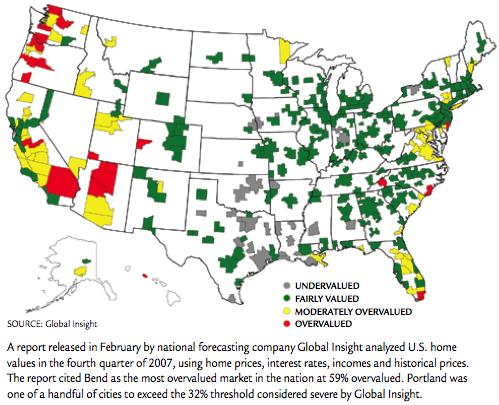

A national report by the economic forecasting company Global Insight released in February identified Bend as the most overvalued housing market in the U.S., at 59% above true market value. The same report pegged metro Portland as 32% overvalued. The cities where home values have dropped precipitously, such as Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Phoenix, were identified as less overvalued than Portland in the Global Insight report because their markets began correcting earlier.

“There is this surface veneer that we as Oregonians want to believe that the meltdown isn’t happening here,” says Tim Duy, a University of Oregon economist and director of the Oregon Economic Forum. “I keep telling people, the market in Oregon started to rise later than in the rest of the country. We’re just lagging the cycle by 12 to 18 months here. It’s a story that people don’t want to hear for a whole host of reasons. But that is what’s happening.”

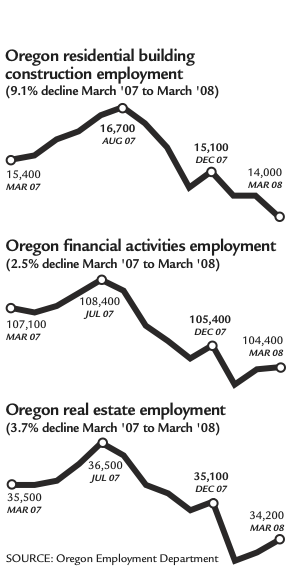

OREGON’S ECONOMY has managed to side-step recession so far. But the state has lost thousands of housing-related jobs, defaults are on the rise, banks are scrambling to mitigate losses and mortgage brokers and real estate professionals are working harder and earning less.

|

Between March 2007 and March 2008, Oregon lost 8,500 jobs in real estate, finance, construction, wood products and logging, according to the Department of Employment. Statewide foreclosure filings in March were up 119% from March 2007, according to RealtyTrac, a national research firm. Some of the state’s most successful homebuilders, such as Renaissance Homes and Ryan Olsen Development, have been hit hard with foreclosure. The lack of demand for building supplies has weakened an Oregon timber industry already slumping from low log prices.

Home building has slowed because the Oregon housing market is out of balance, clogged with debt-burdened sellers who borrowed beyond their means:

• In Lincoln County, sales of all homes fell from 3,392 in 2005 to 1,734 in 2007.

• In Central Oregon, home and residential property sales dropped from 10,541 in 2005 to 4,950 in 2007.

• In Douglas County, oversupply peaked in January with enough inventory on the market to last 20.4 months. (A healthy market has about six months of inventory.)

• In Curry County, a home’s average number of days on the market before selling ballooned to 221 in February.

• Metro Portland hit a record high of oversupply in January, with 12.8 months of inventory.

Even Homer Williams, the characteristically optimistic Portland developer who helped build the Pearl District and South Waterfront, paints a bleak picture of the current market. “Until the ground stops moving and people get a sense of where we’re heading, there’s not going to be any movement in the market,” he says. “Unless people have a specific reason to move, like a job transfer or a divorce, they’re not buying.”

Williams has found out the hard way that Portland’s appetite for condominiums has faded. His $40 million 2121 Belmont project in southeast Portland went on the market last year but had not sold a single unit by mid-March, when he was forced to convert to apartments. Portland’s oversupply problem is easy to see in the condo market, with two years worth of inventory on the market, and in the new subdivisions that have sprouted up in the suburbs. It is less apparent within Portland’s close-in neighborhoods, but even those submarkets have seen price reductions. Brian Spear, an agent with John L. Scott who specializes in inner Northeast Portland properties, normally represents equal numbers of buyers and sellers. Earlier this spring, he found himself with nine clients all hoping to sell, five of whom had never lived in their homes. “The investor market is a huge part of the marketplace, and it has dried up,” says Spear. “A lot people got in over their heads, and everyone is rushing to the exits.”

OREGON’S MORTGAGE BROKERS — those who are still in business — are acutely aware of the connection between Wall Street’s troubles and Oregon’s. The rates they offer are dictated by global markets; the loans they sell are bought by Wall Street investors — at least they were prior to the meltdown. Since last July demand for mortgage-backed securities has plummeted on Wall Street, as has the number of jobs for loan officers in Oregon. At the end of 2006 there were 13,112 licensed mortgage originators in Oregon; by the end of February there were 8,157.

About 50 of the survivors gathered in a conference center in the KOIN tower in downtown Portland in mid-March, after a wild weekend on Wall Street when the magnificent collapse of Bear Stearns raised ominous questions about the state of capital markets. Ken Perry, CEO of Broker Knowledge Group, a Vancouver, Wash.-based continuing education provider for mortgage originators, opened his talk with a stark list of monumental changes in the industry: Bear Stearns down and nearly out after investing too exuberantly in mortgages; mortgage giants New Century and Option One shut down and bankrupt; ever-tightening clampdowns from banks and mortgage insurance companies; ever-changing guidelines and standards that make for longer processing times and more rejections; fewer products to sell and fewer qualified borrowers to sell them to; less money to move and less business.

“Raise your hand if you have not been shaken by this,” Perry said.

Not one hand went up.

The discussion was led by Perry and Mark Aalto, a senior loan officer for First Pacific Mortgage in Clackamas. Aalto had his best year ever in 2005, closing $62 million in loans. In 2006 he closed $52 million. He was on pace to equal that in 2007 when the meltdown hit and the money stopped flowing freely.

|

It is a scenario that mortgage originators throughout Oregon know well. “It’s really difficult to find financing right now because everyone is cutting back on their loan programs and the mortgage insurance companies aren’t backing a lot of the loans we used to offer,” says Renee Spears, president of Portland-based Rose City Mortgage Specialists. “I’ve been in the business for over 20 years, and this is the worst I’ve seen it.”

Spears and Aalto built their businesses the old-fashioned way, through referrals and loan volume. Others in the industry specialized in riskier loans, which paid larger commissions. Some of these loans start at deceptively low teaser rates and reset at higher permanent rates. Others require that the homeowner pay only a portion of the interest each month, losing rather than gaining equity.

At the peak of the housing boom, more than 8,000 out-of-state mortgage brokers were licensed to work in Oregon and many of them specialized in high-risk loans. Of the 203,360 home loans made in Oregon in 2006, 51,556 were sub-prime, according to data collected by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. That doesn’t include the profusion of “no doc” loans, sometimes criticized as “liar loans” because they allow borrowers to state income without proving it.

Now that the mortgage insurance companies have clamped down, the riskiest loan products are history, and so are many of the brokers who specialized in selling them, including about 4,000 out-of-state mortgage brokers who are no longer licensed to work in Oregon. But the dodgy loans they sold remain on the books. Borrowers already have seen dramatic increases in their monthly payments. Some will see their payments double.

“We’ve gone from an economy based on greed to an economy based on fear,” says Aalto.

THE CLAMPDOWN by the insurance companies and banks doesn’t just shrink the pool of qualified buyers. It also can trap homeowners and speculators who have invested beyond their means. They no longer have the option of borrowing from the future value of their homes, because that value is in doubt.

Thus the rise of the short sale.

Margot Murphy, a Portland real estate broker with RE/MAX and author of an 80-page how-to short sales guide, conducts about two training sessions per month about how to close short sales. She recently presented in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, and she is seeing more demand for her expertise locally as well. One of her clients owes $1.25 million on a home he built on Rocky Butte; after failing to attract any offers with a price of $997,000 Murphy dropped it to $797,000 and received two offers, both below $600,000.

Murphy emphasizes that short sales take time and patience. Sellers must submit detailed paperwork explaining their hardships and proving they have no hidden sources of income or savings. Brokers must convince lenders that the sales price is the best the market will bear. Loss mitigators must balance a complex equation of debt and value to meet fiduciary responsibilities. In any market, the process is highly negotiated and frequently frustrating. In the current market, it can be a nightmare.

But like them or not, short sales will not be going away any time soon. On Easter Sunday, 20 new posts on Portland’s Craigslist website advertised properties as short sales. The listings varied from a $169,900 “Investors-Rehab Special” to a discounted $499,950 new home near a creek and a golf course. Even if these homes draw offers, they could remain in limbo for months while lenders attempt to untangle a complex web of creative financing. They will also compete with a growing number of bank-owned properties on the market, such as the home in Happy Valley that was purchased for $748,900 in 2005, appraised at $1.2 million in 2006, and put back on the market for $599,000 in 2008 by Premier Asset Services, a wholly owned subsidiary of Wells Fargo Bank that specializes in foreclosure.

But as is the case in the rest of Oregon’s housing market, supply is overwhelming demand. “I’m getting a lot of great deals, but I’m having a hard time selling,” says Michael Mason, president of Magic Kingdom Properties in St. Helens, which buys 20-30 distressed properties per year as investments. “Nobody’s got any money because credit is so tight.”

But as is the case in the rest of Oregon’s housing market, supply is overwhelming demand. “I’m getting a lot of great deals, but I’m having a hard time selling,” says Michael Mason, president of Magic Kingdom Properties in St. Helens, which buys 20-30 distressed properties per year as investments. “Nobody’s got any money because credit is so tight.”

Credit is tight for a reason. Oregon’s banks, large and small, are scrambling to keep their losses at a minimum after suffering precipitous drops in their stock prices. Bankers are working overtime, re-examining terms, restructuring loans, and increasingly, initiating foreclosure.

RANDY SEBASTIAN MOVED into the Bend market in January 2006 for the same reason other homebuilders did. There were fortunes to be made and demand seemed insatiable. Sebastian, president of Lake Oswego-based Renaissance Homes, got financing to build two large subdivisions in Bend, including the $120 million, 210-home Renaissance Ridge. But while he was building the market was crashing. Median prices on homes sold in Bend in the first quarter dropped by 12% from a year ago. He tried price reductions, gift certificates, free Mercedes Smart Cars to buyers, even offers to buy down interest rates. Still he was unable to keep current with his loan payments because sales were slow.

On March 7, Sebastian received a letter from KeyBank informing him he had five days to pay the bank $13 million. When he could not pay, KeyBank filed for foreclosure.

Sebastian’s experience was extreme but not unique. The same market forces knocked Lake Oswego-based Ryan Olsen Development into insolvency. Olsen launched his company in 2002 with the goal of bringing inner-Portland-style craftsman homes to the suburbs. By 2005 he was running one of the fastest-growing private companies in Oregon. His revenues leaped from $915,000 in 2003 to $7.6 million in 2006, according to Inc. magazine. But Olsen’s luck has run out in outer Gresham, where his partially completed, 17-lot subdivision of homes originally priced in the “low 600s” languishes vacant and in disarray. The finished homes there are listed as short sales, while the undeveloped lots have been repossessed by Sterling Savings Bank and are up for sale as bank-owned properties.

Sebastian’s experience was extreme but not unique. The same market forces knocked Lake Oswego-based Ryan Olsen Development into insolvency. Olsen launched his company in 2002 with the goal of bringing inner-Portland-style craftsman homes to the suburbs. By 2005 he was running one of the fastest-growing private companies in Oregon. His revenues leaped from $915,000 in 2003 to $7.6 million in 2006, according to Inc. magazine. But Olsen’s luck has run out in outer Gresham, where his partially completed, 17-lot subdivision of homes originally priced in the “low 600s” languishes vacant and in disarray. The finished homes there are listed as short sales, while the undeveloped lots have been repossessed by Sterling Savings Bank and are up for sale as bank-owned properties.

Olsen’s business phone has been disconnected.

Most banking executives say they prefer to avoid foreclosure, but in some cases it is the best, or only, option. “The process of foreclosure can have a benefit to the bank in that it does bring the borrower to the forefront and force them to deal with their problem,” says Brad Copeland, Umpqua Holding Corp. senior executive vice president and chief credit officer.

Umpqua Holding, based in Portland, bought out several banks in California prior to the real estate slowdown there, and the bank has assembled a “special assets” team to handle inherited loans that have become problematic. “In these kind of times, I can tell you that everybody’s workload in that department is stretched,” says Copeland.

Umpqua’s stock price sank more than 40% between April of 2007 and April of 2008. During that same period Bend-based Cascade Bancorp fell more than 60%. Cascade’s non-performing assets ballooned from $3 million in 2006 to $55.7 million in 2007 as a result of loans for building projects. “The real estate market is more difficult for all banks,” says Cascade CEO Patricia Moss. “There are more people who aren’t able to pay, and that’s creating more work in the system.”

It is also creating serious losses. Washington Mutual announced on April 8 it would close 11 home loan centers throughout Oregon as part of a massive restructuring forced by $1.1 billion in losses over the first quarter. WaMu bet heavily on sub-prime loans and is paying dearly as foreclosure rates rise.

The largest mortgage lender in Oregon, Wells Fargo, reports a foreclosure rate 20% below the industry average, but the largest provider of refinancing loans in Oregon, Countrywide, makes no such feel-good claims. Countrywide’s national foreclosure rate doubled from .8% in February 2007 to 1.6% in February 2008, and the company is facing multiple lawsuits for alleged abuses of the foreclosure system.

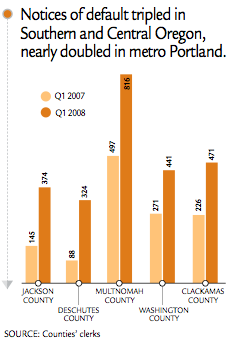

Through the end of 2007, Oregon’s default and foreclosure rates were well behind those of other states. But they are rising. Notices of default have tripled in Jackson and Deschutes counties from the first quarter of 2007 to the first quarter of 2008, and have nearly doubled within the Portland metropolitan market during the same time period. The Pew Center for the States projects that one out of 34 homeowners in Oregon faces a significant risk of foreclosure by 2010.

That isn’t necessarily bad news — for investors with cash, not to mention bankruptcy attorneys and default servicing companies.

One such Oregon business that stands to benefit significantly from the current housing market is Wilshire Credit Corp. of Beaverton, which handles problematic mortgage loans on behalf of Wall Street investors, including collections and foreclosure. Wilshire was founded by infamous Portland financier Andrew Wiederhorn and sold to Merrill Lynch for $52 million in 2004. As the national housing market has crumbled, Wilshire has grown to more than 800 employees and added a second office in Salem. According to a Merrill Lynch spokesman, Wilshire serves as intermediary for about 150,000 mortgage loans worth more than $15 billion.

What does it say about the state’s economy when one of the biggest winners is the local foreclosure mill?

|

THERE ARE TWO BASIC views about how well Oregon’s economy will hold up amid the housing slump. One holds that the boom was less extreme here so the bust will be minor, especially when balanced against the strength of the state’s export economy. The other view counters that the housing party came to Oregon late, meaning the hangover will be delayed but just as painful as in other states.

Only time will tell which forecast is more accurate because the immediate landscape can be contradictory, and economists disagree about what the numbers mean.

Seasonally adjusted initial unemployment claims decreased in February after seven consecutive monthly increases, but then rose again in March. Oregon residential building permits also made a surprising recovery, from 1,012 in January to 1,850 in February. Oregon’s manufacturing, agriculture and clean tech sectors appear to be holding up well, with new state subsidies bringing investments into renewable energy. The weakened dollar has boosted large exporters, such as Nike and Intel, while surging commodity prices have helped the state’s agricultural sector.

Joe Cortright, an economist with Impresa Consulting in Portland, argues that Oregon’s export-heavy, diversified economy is better positioned to deal with a recession than the rest of the country. “We are going through one of the biggest corrections we’ve ever seen in the housing market and Oregon’s economy is faring at least as well and maybe a little bit better than the rest of the country,” says Cortright. “We have transformed our economy from one that is dependent on the housing cycle to one that isn’t.”

But even the most positive of prognosticators predict it will take time for the myriad problems created by the mortgage meltdown — especially the growing backlog of short sales and foreclosures — to work their way through the system, so that the system can be rebuilt and consumer confidence can be restored.

Oregon state economist Tom Potiowsky, no fan of doom and gloom, expects the economy to return to more typical levels of growth later this year — “but don’t expect a big bounce-back in 2009.”

Developer Homer Williams agrees. “These downturns always last a little longer than people think they will,” he says. “It’s not just a few months; it’s often a year or two years. We’ve got some time to go on this.”

Mark McMullen of Moody’s forecasts a relatively mild Oregon recession that will be mostly isolated to the housing sector, with the last indicator to recover being home prices.

“Developers have cut back on building, but now we’re getting all these foreclosures coming onto the market,” he says, “so we’re still seeing too much supply. Until that balances, you won’t see a recovery.”

U of O’s Tim Duy agrees. His recommendation: “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst.”

To comment, email [email protected].

Mark Aalto, with First Pacific Mortgage in

Mark Aalto, with First Pacific Mortgage in Margot Murphy, a broker with RE/MAX who specializes in short sales, shows the view from the home of a client who owes $1.25 million on his mortgages. She listed the Rocky Butte property at $997,000 and reduced the price to $797,000 after receiving nothing but “low-ball” offers.

Margot Murphy, a broker with RE/MAX who specializes in short sales, shows the view from the home of a client who owes $1.25 million on his mortgages. She listed the Rocky Butte property at $997,000 and reduced the price to $797,000 after receiving nothing but “low-ball” offers.