Businessman and environmentalist Duncan Berry began with the question of how to keep local seafood in Oregon. His answer was Fishpeople.

Businessman and environmentalist Duncan Berry began with the question of how to keep local seafood in Oregon. His answer was Fishpeople.

BY HANNAH WALLACE

|

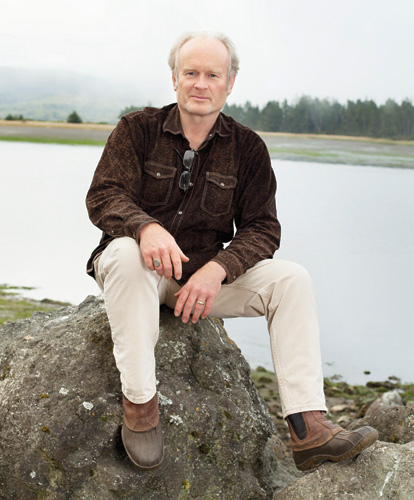

Duncan Berry at the Salmon River, with the 529-acre Westwind behind him. Berry is on the board of the nonprofit Westwind Stewardship Group.// Photo by Sierra Breshears |

When Duncan Berry moved back to the Oregon Coast six years ago with his wife, Melany, he had no plans to return to the fishing industry. A longtime environmentalist and onetime captain of a salmon troller, Berry had just sold the Apparel Source, his $60 million-a-year textile company, and was eager for another venture that would combine his entrepreneurial background with his environmental ethics. In the shadow of Cascade Head, the rugged headland north of Lincoln City, Berry launched an environmental consulting business called Ecosystems Services.

In 2010 Berry served on a state task force that debated whether the sea surrounding Cascade Head should be deemed a protected marine reserve. Ultimately, the Cascade Head Marine Reserve community team recommended that a 30-square-kilometer area be protected. During the nine-month period of working alongside fishermen, conservationists, business leaders and politicians, Berry got an up-close look at the fishing industry’s supply chain.

What he saw was a disconnect between sophisticated urban consumers — who wanted to know where and how their fish were caught — and seafood processors, to whom “a fish is a fish is a fish.”

“I thought, ‘How do you unite a woman sitting at a kitchen table in Portland with a fisherman who is 60 miles off the Coast in his boat?’” says Berry.

Surprisingly, for a state with a vibrant $148 million fishing industry, there is a huge gap in the value-added segment of the market. A few small-scale operations, such as Sweet Creek Foods in Elmira and Sea Fare Pacific in Coos Bay, process and market Oregon fish, but unlike other coastal states, Oregon has no dominant seafood brand that markets a value-added, locally caught fish. Meanwhile, much of Oregon’s catch is shipped elsewhere. Though there is no hard data, Brad Pettinger, executive director of the Oregon Trawl Commission, estimates that more than half of Oregon’s seafood harvest is exported each year.

“What’s happening is that all this incredible protein is going elsewhere, and those people are making money on our natural resources,” says Berry. “That is offensive to me as an Oregonian.”

So Berry, 57, set about creating a company that would capture some of Oregon’s rich seafood harvest for fish-loving Oregonians. After 16 months of research — interviewing everyone from fishermen to consumers about what was and wasn’t working for them regarding fish — Berry and investment partner Kipp Baratoff came up with an innovative product: a ready-to-eat, sustainably caught seafood meal, packaged in a foil “retort” pouch.

Christening his new company Fishpeople, Berry planned to launch four products in late September at New Seasons Market and Whole Foods in Oregon and Washington: salmon in a chardonnay-dill cream sauce; Thai coconut-lemongrass tuna; coconut-yellow curry tuna; and smoked salmon and oyster chowder. Almost everything about the product, down to the eye-catching logo (designed by Portland’s Sandstrom Partners), is made or harvested in Oregon.

Berry and his team — which at the beginning consisted of Melany, chef Christine Finson and brand manager Jodie Emmett de Maciel — conducted a dozen or so focus groups, mostly with female consumers in the Portland area. (Women tend to make food-buying decisions more than men.) One of the surprising revelations was that women, while they love eating omega-3-rich fish, avoid cooking it at home because of the bones, scales and odor.

“Women have an uncomfortable relationship with seafood,” says Berry. Though Oregonians, particularly Portlanders, have a reputation for being self-sufficient when it comes to food — witness the explosion of backyard gardens and newfound interest in canning and chicken rearing — this doesn’t apply when it comes to fish.

“Your general consumer is very afraid of cooking seafood,” agrees Nancy Fitzpatrick, executive director of both the Oregon Albacore Commission and the Oregon Salmon Commission. “They don’t know what to do with it. Therefore, they don’t buy it.”

In this squeamishness, Berry saw an opportunity. The retort pouch — made of food-grade laminate that is BPA-free — eliminates the smell and the mess of cooking raw fish. The fish is already scaled, filleted and cooked in a sauce made by Portland-based Heritage Specialty Foods, which sources nearly all the ingredients in the Pacific Northwest. The consumer’s task consists of throwing the pouch into a pot of boiling water for three minutes, opening it and pouring it over pasta or rice.

Though retort packaging for seafood is the norm in Asia and Europe, it may pose a stumbling block for Northwest consumers, whose limited experience with the technology is likely to be Tasty Bite vegetarian Indian meals. And the pouch may be BPA-free, but it’s not recyclable in its current form. Berry admits this is his biggest challenge, even as he argues that retort pouches have a lighter environmental footprint than cans. He says he and a consortium of businesspeople are working on the recycling issue, “because retort is here to stay.”

Ryan White, local grocery buyer for Portland-based New Seasons Market, initially had doubts about carrying the product precisely because of the unfamiliar packaging. “We don’t have anything on our shelves quite like this,” says White. But once he and Joel Dahll, director of grocery, tried the salmon in chardonnay cream sauce, White says it was a “no-brainer.” He bets customers will dismiss any hesitations about the pouch as soon as they taste the product themselves. The suggested price for a 7-ounce meal is $5.99.

White thinks Portlanders will also be hooked by Fishpeople’s socially and environmentally responsible ethos. The company’s story starts with sourcing troll-caught Oregon fish (one of the most sustainable fishing methods, trolling minimizes bycatch) and keeping jobs for fishermen, medium-sized processors and sauce-makers in Oregon. It includes a “keeping it regional” approach that will limit distribution of the entrees to just Oregon, Washington and Idaho. Northern California may soon follow.

“We don’t want to ship a ton of Northwest tuna to Maine,” says Berry, who thinks that the future of business will be in regionally based models. In the Northwest, Berry is targeting 600-odd retail stores, including New Seasons, Whole Foods and Seattle’s PCC Natural Markets. He’s also talking with food-service providers such as Aramark and Sodexo, who are keen on carrying a bulk version of the product.

Berry is firm that he has no desire to expand until he can prove that a regional model works. If it does, he would consider expanding, but instead of shipping Oregon albacore across the country, Berry would invest in a new supply chain in each region. Berry hopes to have a “Fishpeople Northeast” that would take advantage of Maine’s fresh lobster and employ a New England business to make sauces from local ingredients. “We’d keep the dollars there in the community,” says Berry. Meanwhile, the legal, financial and marketing arms of the company would remain in Oregon.

Berry is firm that he has no desire to expand until he can prove that a regional model works. If it does, he would consider expanding, but instead of shipping Oregon albacore across the country, Berry would invest in a new supply chain in each region. Berry hopes to have a “Fishpeople Northeast” that would take advantage of Maine’s fresh lobster and employ a New England business to make sauces from local ingredients. “We’d keep the dollars there in the community,” says Berry. Meanwhile, the legal, financial and marketing arms of the company would remain in Oregon.

Fishpeople’s initial run of 10,000 units is small by industry standards. Finding processors on the Coast who would work with such small numbers was a challenge for Fishpeople’s head of operations, Charlie Slate. Formerly the sustainability specialist at fish-processing giant Pacific Seafood in Clackamas, Slate had lengthy conversations with processors, explaining Fishpeople’s mission to keep money, jobs and fish in Oregon, before he found the right matches. The company will be sourcing Chinook from Skipanon Brand Seafood in Warrenton; albacore from Oregon Seafoods in Coos Bay; and smoked oysters from Tillamook’s T&S Oyster Farm, which farms in Netarts Bay. Barnacle Bill’s Seafood Market in Lincoln City is smoking the salmon in the chowder.

Fishpeople is also contracting with Oregon Seafoods to use its retort packer, which owner Mike Babcock bought two years ago when he launched Sea Fare Pacific, his line of once-cooked Oregon albacore.

A relatively short supply chain — working directly with USDA-inspected processors like Oregon Seafoods and having regular conversations with them, the fishermen and the sauce kitchen — will allow Fishpeople to have a traceable product. Consumers can plug in the batch number on fishpeopleseafood.com and find out which vessel caught their fish.

Sustainability is also integral to Fishpeople’s brand. While researching the health of local fish stocks and which fishing methods trap the least amount of bycatch, Berry and his crew consulted the respected seafood ratings put out by the Blue Ocean Institute, the Marine Stewardship Council and the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Ultimately, none of these provided enough nuanced information on Oregon fisheries, so they wrote their own Oregon-centric seafood ratings on seven species of fish.

Berry hasn’t always built businesses around his environmental ethics. When he ran the Apparel Source, Berry had a crisis of conscience. He had been sourcing conventional cotton when he realized that it was doused with toxic insecticides that were hazardous to workers and watersheds. On the verge of leaving the company, Berry sought advice from environmentalist Paul Hawken, author of The Ecology of Commerce. “He told me I had greater leverage making change as a captain of industry than I did as a citizen,” Berry recounts. So he began sourcing organic cotton and soon started Greensource, an organic T-shirt division that supplied Walmart and Target. Before he sold it, Greensource was one of the largest organic-cotton textile companies in the world.

The idea that business can be a force for good has stuck with Berry. With Fishpeople, he is betting that Oregonians will vote with their forks by buying a product that is in sync with their values as well as their taste buds.

Making a profit is just one of many returns Berry hopes to see. “Once we start building volume, we can start having a positive impact on coastal communities and habitats,” Berry says. “That’s the day I’ll be happy and fulfilled.”

Hannah Wallace is a Portland journalist who writes about food politics for regional and national publications. She can be reached at [email protected].