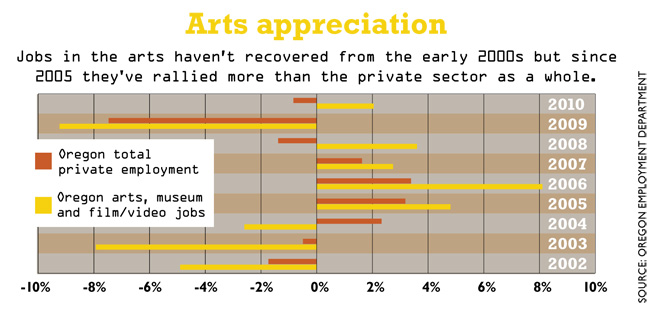

Hardly. Arts-related jobs have grown faster than overall employment.

Hardly. Arts-related jobs have grown faster than overall employment.

{artsexylightbox}{/artsexylightbox}

BY BRANDON SAWYER

Click on any graph to view larger. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Out of the ashes of the Great Recession of 2007-2009, Oregon’s arts-related economy seems to have fared better than the private sector as a whole. Arts employment has by no means regained its 2008 peak, but many creative sectors are thriving.

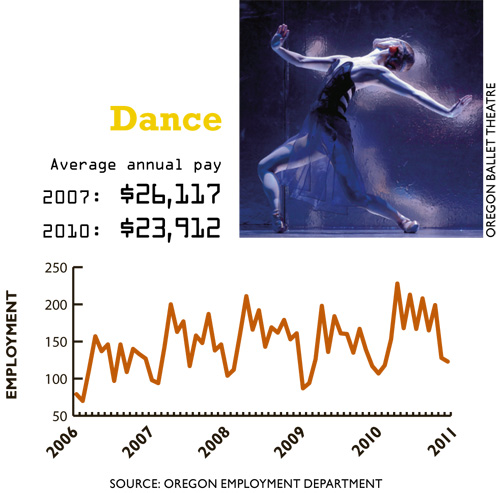

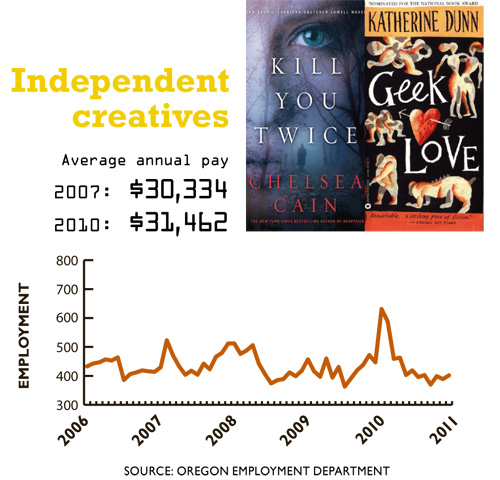

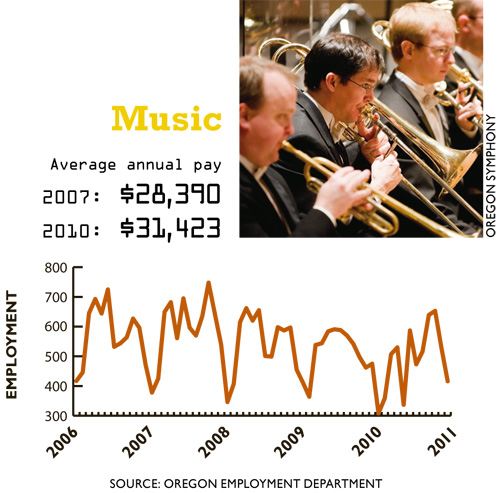

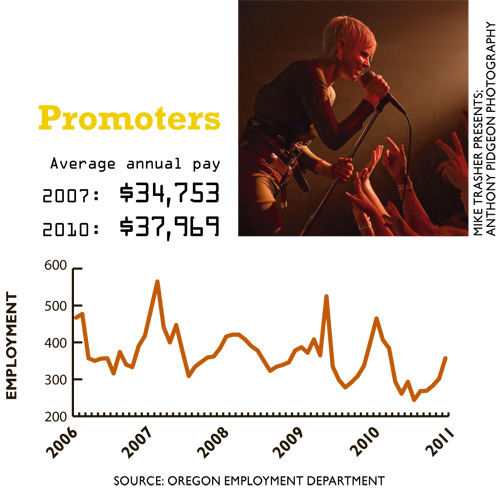

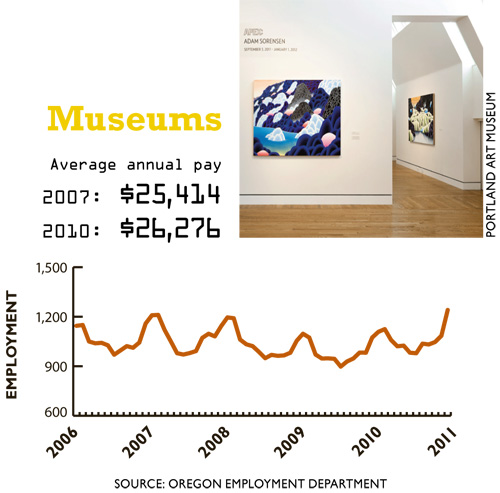

The arts are a nebulous universe with many self-employed, part-time and seasonal workers. To get a handle on it, Nick Beleiciks, state employment economist at the Oregon Employment Department, gathered data for those covered by unemployment insurance, including the performing arts (theater, dance and musical groups), independent writers and performers, promoters, museums and motion pictures (production, distribution and theaters).

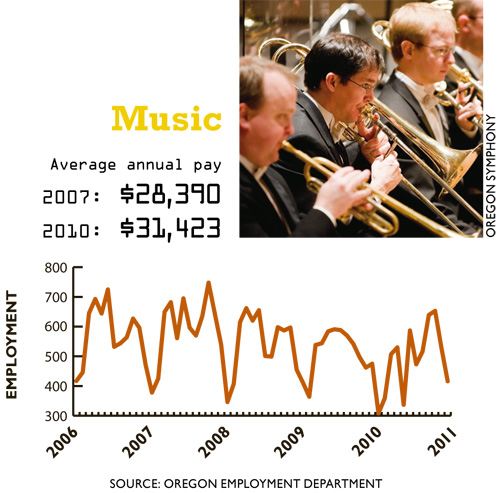

These jobs grew 3.6% in 2008, the first full year of the recession, but dropped 9.2% in 2009. But in 2010, when total employment continued to slide, arts jobs grew 2% and have kept rising. In the first six months of 2011, they increased 1.5% over the same period in 2010.

“Between 2007 and 2010 the industry lost 4% employment,” says Beleiciks. “That compares to the overall loss of 9.5% of private jobs. In terms of employment the arts-related industry did do a little better than overall industry.”

That’s good news for the growing community of artists moving to Oregon. The National Endowment for the Arts reports that in 1990 artists represented just 1.4% of Oregon’s labor force, the same as the U.S. overall. In 2000, that grew to 1.6% and by 2005-2009 artists represented 1.7% of the state’s workforce — 20% greater than nationwide. Oregon tied with Vermont for third place, behind only New York and California.

Oregon’s enthusiasm for local talent, along with cultural tourism from outside the state, has helped boost arts employment and revenue and preserve the arts through the economic downturn.

“Arts organizations in Oregon overall rely more heavily on earned income than arts organizations in other places,” says Christine D’Arcy, executive director of the Oregon Arts Commission and Oregon Cultural Trust. Greater reliance on earned income has proven a boon in times when charitable contributions and grants have dropped.

The Oregon Arts Commission produces a Creative Vitality Index each year, 60% of which is based on “arts participation” and the remaining 40% on arts-related employment. In 2010, the index rose 0.03 to 1.02 for Oregon, compared to the national baseline of 1.0. Multnomah and Washington counties’ index was much higher at 1.58.

Not only do Oregonians fervently patronize the arts, says D’Arcy, but Oregon draws cultural tourists, especially to Portland. “When you combine the quality of the arts and cultural programming with a very livable city, craft beer and wine, and a city that’s easy to get around in, people want to come here and experience culture.”

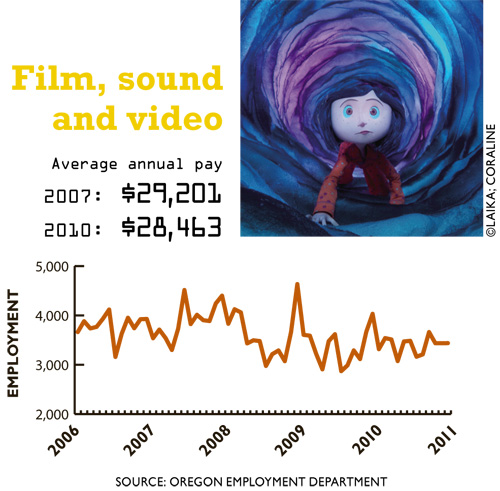

That vibe has helped Portland draw film and TV productions. Vince Porter, executive director of the Governor’s Office of Film and Television, has managed state incentives to draw and keep projects that pack a big economic impact. He’s helped land three TV shows in Portland. “With Leverage, Portlandia and Grimm,” he says, “all of them have been in their own world reasonably successful.”

He estimates that out-of-state film and video production spent more than $110 million in Oregon last year. “When your previous record was $62 million, it’s a pretty big increase, so of course we’re going to try to keep it at that level but… we have to compete with so many other places.”

Outside of film, Porter sees promise in the state’s animation studios, such as Laika in Hillsboro and Bent Image Lab in Portland.

“I don’t know if there’s another city in the country that has the amount of stop-motion animation talent as the Portland metro area. Combining that with some of the tech talent and design talent that are here, there’s some new cool things happening.”

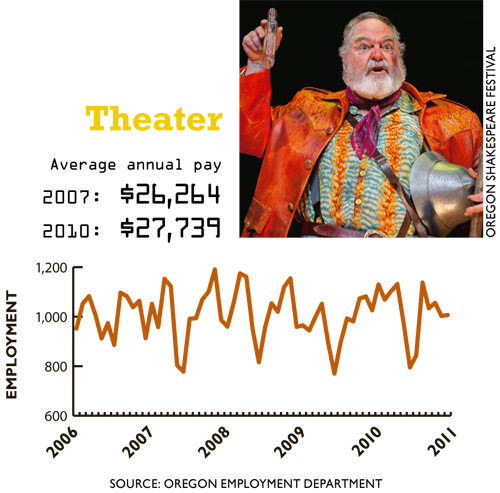

Ashland’s Oregon Shakespeare Festival is another shining star in the arts universe with roughly 600 employees. In 2010, the nonprofit’s 75th season, it had an economic impact of $179.6 million, a 3% increase over 2009. Program revenue grew 8% to $19.3 million as attendance peaked to 414,783. Even operating contributed income grew 6% to $6.9 milion.

“Seventy-five to 78% of our income is earned income so we depend on that,” says Amy Richard, media and communications manager.

The Eugene Symphony also has enjoyed unflagging community support. About 50% of its income is from tickets, according to Maylian Pak, interim executive director. Most orchestras get about 40% of income from tickets, she says.

Support has been so solid that the symphony has balanced its budget for 19 consecutive seasons.

“I believe the individuals who support the arts are so passionate about what we do that they make it a priority,” Pak says.

Individuals account for about 80% of most arts organization’s contributed income, business contributions are usually less than 10%, and the rest comes from foundations and government, according to Virginia Willard, the recently retired executive director for Business for Culture and the Arts in Portland.

These funding sources have less to contribute than before the recession, and arts organizations in Oregon and nationwide are struggling despite strong patronage.

Willard stresses the value of the arts as part of a strong economy. “It is an industry that creates jobs,” she says. “They are not jobs that can be exported.”

Brandon Sawyer is research editor for Oregon Business. He can be reached at [email protected].