A transcontinental flight or all-night study session renders even the sharpest among us a bit fuzzy headed. Now for the first time researchers at OSU have shown that disrupting our “biological clock” does more than make people tired.

A transcontinental flight or all-night study session renders even the sharpest among us a bit fuzzy headed. Now for the first time researchers at OSU have shown that disrupting our “biological clock” does more than make people tired.

BY LINDA BAKER

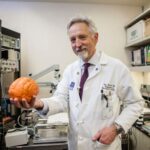

A transcontinental flight or all-night study session renders even the sharpest among us a bit fuzzy headed. Now for the first time researchers at Oregon State University have shown that disrupting our “biological clock” — a genetic mechanism tuned to 24-hour cycles of light, dark and sleep — does more than make people tired. It can also accelerate neurological problems and trigger loss of motor function and premature death. Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the research project involved fruit flies with two mutations, one that disrupts the clock and another that causes flies to develop brain disorders during aging. These double mutants had a 32%-50% shorter lifespan and lost motor function much sooner than flies with normal clocks, says Jadwiga Giebultowicz, a zoology professor and team leader. She says the new research suggests that loss of clock function is linked to neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, which often present with sleep disruptions. Fruit flies are an “ideal aging model,” adds Giebultowicz, because one day in the life of a fly equals one year in the life of a human. The next step, she says, is “to figure out how to rejuvenate the clock to give beneficial health effects.”