Oregon’s tall wood building industry moves forward despite setbacks

In a small rural town, a quiet plywood factory houses a groundbreaking innovation in construction. Here in the timber town of Lyons, population 1,204, 96-year-old veneer manufacturer Freres Lumber runs the first mass-plywood operation in the world. At the heart of the $35 million plant stands a graceful 22-foot arch, a test piece of the material’s strength and flexibility. It’s made of one-eighth-inch panels stacked three or four thick at right angles, glued by a hydraulic press and cut out by a giant robotic saw. The ultra-strong panels earned a certification in August to bear the weight of buildings.

Three years ago, Oregon’s embattled rural timber industry proclaimed it would rise again atop wooden skyscrapers. Now the dream is turning to reality as regulations lift, factories ramp up production and the nation’s premier mass-timber research arm expands its offerings.

It has not been a smooth ride for the sector. In March, a 1,000-pound cross-laminated timber panel cracked at Peavy Hall, a mass- timber building that houses Oregon State University’s forest sciences department in Corvallis. The event vindicated mass timber skeptics. Engineers traced the accident to the glue in the panel, manufactured by lumber company D.R. Johnson, coming apart, or “delaminating” (CEO Valerie Johnson did not respond to requests for an interview). Meanwhile, developer Project^ shelved its much-anticipated Framework, a 12-story timber apartment in Portland. The firm cited inflation, mounting construction costs and “market challenges.”

Rob Freres, president of Freres Lumber.

Rob Freres, president of Freres Lumber.

Many groups have yet to hop onboard the mass-timber train. Contractors and architects lack expertise in the emerging material. Environmentalists caution against harvesting more wood from fragile forestland, while concrete producers flex political muscle to strand mass timber in wet cement.

But these headwinds haven’t wiped out the sector’s prospects. In August the Oregon Building Codes Division approved timber towers of up to 18 stories. A $12 million cross-laminated timber research lab is rising at Oregon State University alongside the wooden skeleton of Peavy Hall. Nationwide, at least 35 tall wood buildings, from seven to 24 stories, are pending approval.

“The phone is ringing so much,” Freres Lumber’s president, Rob Freres, says. “The market is so enormous, there’s enough room for all of us.”

An important part of the evolution of mass timber is the role of academia in propelling the sector forward. The Tallwood Design Institute, a collaboration between Oregon State University and the University of Oregon, is planning a joint master’s degree on timber design, along with a more industry-oriented certificate program. Contractors and other professionals who enroll will learn computer-aided design and quality analysis for mass timber.

The institute has taken the lead in U.S. mass-timber education. At the Corvallis campus, workers erect the beginnings of a $12 million research lab, funded half by Sierra Pacific Industries and half by public dollars. Inside the building, expected to open in summer, researchers will conduct a variety of experiments, including shaking a three-story mass-timber structure to simulate an earthquake. Elsewhere on the grounds, smoking pillars resembling giant cigars char cross-laminated panels to test their fire resistance. A display showcases a rocking wall with U-brackets that dissipate seismic energy.

Peavy Hall, the forestry department’s new home, will feature thousands of sensors to monitor moisture content, temperature and vibrations of the all-wood frame. Researchers will disseminate this data to architects and engineers to inform future designs.

Ian Macdonald, director of the Tallwood Design Institute

Federal funding sustains most research at Tallwood. A congressional appropriation from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and a $450,000 grant from the Economic Development Administration pay for tests of seismic resistance, moisture durability and fire protection. The federal government is showing interest in the disaster resiliency of timber buildings, says Iain Macdonald, director of the institute. Additional funding comes from the state of Oregon and private donors.

“If it’s public funding, the work goes into the public domain and creates a snowball effect,” Macdonald says.

Since cross-laminated timber first gained traction in 2015, tall-wood innovations have advanced at a clip. At a cross-laminated timber presentation at Oregon State in 2015, Freres thought, “Plywood is already cross- laminated. We can do the same thing lumber can with a fraction of the wood fiber.”

His family business cooked up a recipe for cross-laminating thin plywood panels, or veneer, at specific densities and thicknesses. Pivoting from their traditional commodity trade, they hired two structural engineers and built a 185,000-square-foot plant that exceeds the entire U.S. capacity for cross-laminated timber production.

“We really haven’t seen their product applied in the market yet,” says Jim Geisinger, president of the Associated Oregon Loggers trade group, “but I think it’s going to happen fairly soon.”

Panels have been installed in Portland’s Block 76 and on the roof of Peavy Hall. Freres says his plywood offers a number of advantages over cross-laminated timber. It’s denser and, therefore, more fire resistant. The inputs are cheaper. “CLT is going to have trouble finding stress-rated lumber,” Freres says. “They’re going to have to pay a premium to do it.”

Mass plywood’s structural value remains to be seen, but it’s exactly the sort of thinking Macdonald hopes to foster. “We’re lucky we have this research and development ecosystem,” he says. “There’s so much product development that could happen with this.”

Federal and state regulators also want the mass-timber sector to succeed. The Timber Innovation Act in the 2018 Farm Bill before Congress would create a mass-timber research and development program. It would also fund studies of the technology’s environmental footprint.

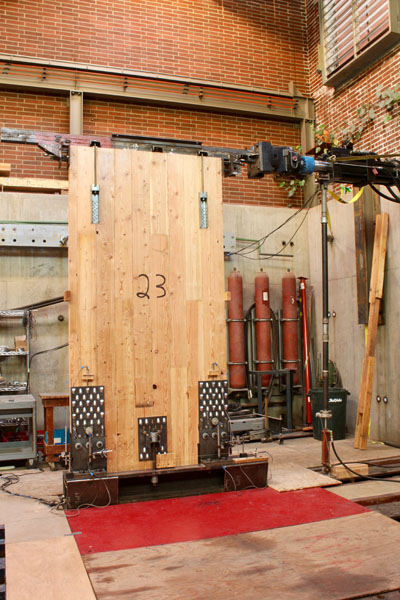

A strength test at the Tallwood Design Institute

A strength test at the Tallwood Design Institute

Oregon took a step ahead of the nation in August, when the state building codes division allowed 18-story mass-timber high-rises. This permits designs on par with the tallest timber building in the world, the 53-meter Tallwood residence at the University of British Columbia, and more than double the height of Oregon’s record holder, the eight-story Carbon 12 apartments in Portland.

Unsurprisingly, concrete producers are waving red flags at the outpouring of public money for the Tallwood Institute and other mass-timber projects. Framework’s public contributions included $6 million from the Portland Housing Bureau and $19.5 million from other government sources.

“Our opinion is that’s not good for the economy,” says Diane Warner, executive director of the Northwest Cement Council, a trade group that represents Oregon-based Ash Grove Cement, CalPortland and two Washington companies. “We need to let the market dictate what makes sense.”

Freres churns through 10 million pounds of logs a day.

Freres churns through 10 million pounds of logs a day.

Cement lobbyists are visiting Salem and Washington, D.C., to fight against the timber towers they’ve dubbed a “public safety threat.” The new buildings, of course, also threaten their clients’ wallets. Warner worries that Oregon “jumped the gun” on the International Code Council’s proposal on mass-timber regulations. While a vote among the council’s members is pending, a committee recommended 14 mass timber proposals for approval.

The industry’s safety concerns are not entirely unwarranted. The National Association of State Fire Marshals pushed against taller wood buildings, writing that no one has conducted live-fire testing on them. Upon further examination of the Peavy Hall failure, engineers marked 85 panels for replacement, according to The Oregonian. The cost of the project ballooned to $79 million.

The cement industry says such failures show that further testing is needed. “No matter how sustainable it might be,” Warner says, “if it falls down, that’s not sustainable in the long run.”

“No matter how sustainable it might be,” Warner says, “if it falls down, that’s not sustainable in the long run.”

The safety record of tall wood buildings in Europe suggests critics’ concerns may be unfounded. Accidents are almost unheard of in the hundreds of disaster-resilient tall wood buildings standing throughout Europe and North America. In an earthquake, panels can be salvaged, and burning panels char like campfire logs, shielding their load-bearing cores. A structural engineer once remarked to Freres, “If the Twin Towers had been built out of this, they wouldn’t have come down on 9/11.”

Along with safety, the sustainability of the new material is up for debate. Mass-timber evangelists are eager to preach the environmental benefits. Macdonald says timber buildings require a foundation a third the size of that used for concrete and steel structures. Engineered wood also takes less heat energy to produce. The finished product can be more easily transported and lifted into place. Timber components come prefabricated, making for speedy installation.

Macdonald sees an opportunity to heal conflicts between environmentalists and loggers. “Mass timber has the potential to reconcile those two,” he says, “environmentalists and the rural economy.”

Yet for all the talk of eco-friendly design, the timber towers still come from trees. It’s debatable how many trees, and of what type, loggers will fell to feed the hunger for mass timber. “I wouldn’t expect a huge increase in the amount of timber harvesting that occurs in Oregon,” Geisinger says. “But what is harvested will be used in a different way.”

Environmental groups say more research is needed before the government subsidizes the emerging technology. “Where we’re concerned is everybody’s going to be excited and throw public money at it, and it’s not going to create better outcomes in the forest,” says Arran Robertson, a spokesman for conservation nonprofit Oregon Wild. “We’re kind of pessimistic about it. We don’t see too many people stepping up to ask questions.”

Freres, whose business devours 10 million pounds of logs each day, says a lack of supply limits his mass-plywood production. He’s eager to thin forests for what he calls “non-controversial” suppressed understory trees. Thinning projects can heal forests by clearing the fuel load for wildfires and opening space for healthy trees to grow. Mass-timber products are composed of thin sheets, so they can be manufactured from smaller logs and reclaimed wood.

Plywood production facilities at Freres Lumber

Plywood production facilities at Freres Lumber

If forests are managed sustainably, timber construction could sequester carbon. A tree cut down for a CLT panel stores carbon. If another tree takes its place, it does the same, reducing overall carbon in the atmosphere.

That “if” is a big one for conservationists. Robertson says Oregon Wild sees potential for cross-laminated timber if it’s indeed harvested from thinning. Yet he fears the timber industry doesn’t share that vision. The Oregon Forest Practices Act, Robertson says, lacks the teeth to protect old-growth forests against industrial clearcuts. Less money goes to “good projects,” such as thinning, selective harvests, and longer rotations.

Despite these concerns, the hydraulic presses are running at full steam.

Updates to codes and legislation, investments in factories and workers, and new education programs are bringing the industry closer to its dream: reviving rural timber communities through a groundbreaking engineered-wood product.

But as with many Oregon timber projects, nothing will go down without a fight.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.