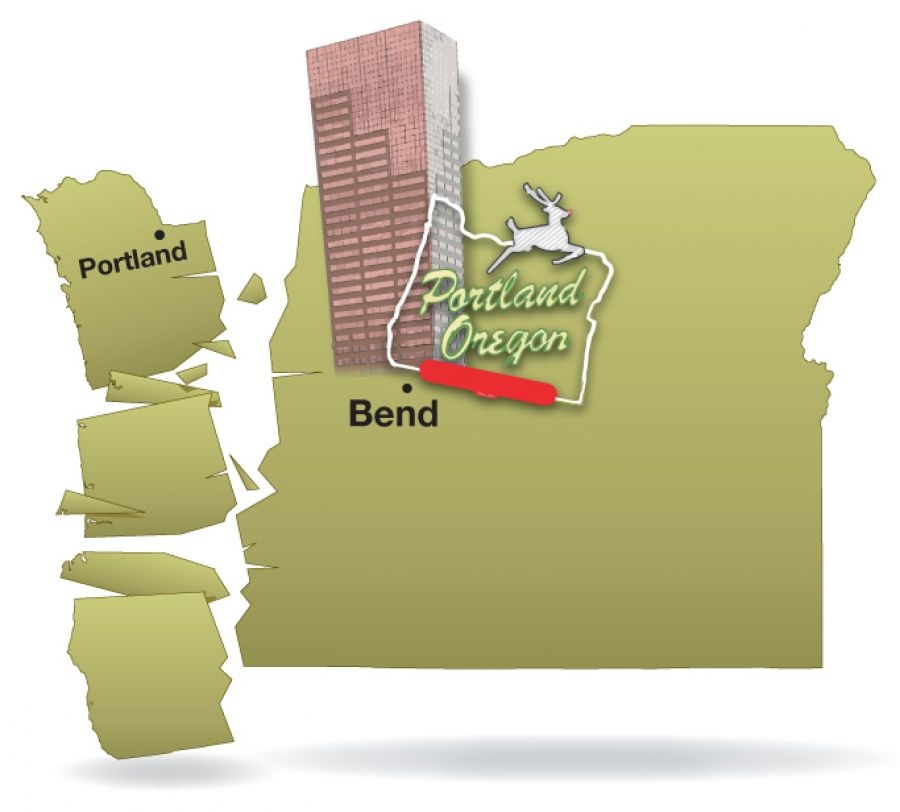

Fear, anxiety and acceptance in the Cascadia earthquake zone.

When Mary Faulkner enters a new room, she goes through a mental exercise. She looks for the exits. She picks a desk to shelter underneath.

“There are a lot of responders and military people who think like this all the time,” says Faulkner, VP of branding and communications at Ferguson Wellman Capital Management.

“I just try to rest my mind. The mind keeps thinking when you don’t want it to think.”

What’s keeping Faulkner’s mind in overdrive is the impending Cascadia Earthquake, a 9.0-magnitude quake predicted to hit the Pacific Northwest — sooner rather than later.

Articles about the megaquake and the catastrophic damage it will unleash appear regularly in the local and national press. According to the latest study, the Cascadia event could cause $80 billion of damage in the Portland metro area and kill tens of thousands of people. On the Oregon Coast, an 85-foot tsunami would threaten 33,000 full-time residents.

These stats keep Faulkner and many other Oregonians on edge and in a near constant state of readiness, or at least awareness.

But earthquake anxiety is not a universal phenomenon for Oregonians living in a seismic zone. Plenty of people, many of them transplants, are more cavalier: They hardly think about the disaster at all, unconvinced it will happen or that they can do anything to prepare if it does.

“The city and state are not going to be able to be there at the level you think they will be there,” Faulkner tells her neighbors.

Susan Laarman falls into the former category.

The communications consultant manages a Facebook page called “Life on a Fault Line.” She feels ready, but still worries about her kids. She was “very anxious” when her son attended Grant High School, which she says “would likely collapse in a quake.” (The school is currently undergoing a major rebuild.)

Now that he’s at the University of Oregon, Laarman still worries, and makes sure he keeps a three-day supply of freeze dried foods and water on hand.

Colleen Kerns, a Nike sales manager, hears a lot about the earthquake at work. But she doesn’t appear too alarmed.

“Some people can’t get it off their minds and are always talking about it,” she says. “When the topic comes up it does concern me but I haven’t taken any action on it.” Kerns does hope the quake hits during work: Nike runs earthquake drills, the newer buildings would likely withstand a quake and plenty of fellow employees would be on hand to help her.

1,650 unreinforced masonry buildings in Portland

45 Schools

35 churches

270 multifamily housing projects

The structures most likely to collapse in the Cascadia megaquake are unreinforced masonry buildings, structures built mostly of brick and stone before 1960. Portland is home to 1,650 such buildings, including 45 schools, 35 churches and 270 multifamily housing projects with over 7,000 residential units.

Government agencies are beginning to make headway on retrofits.

A Portland Bureau of Emergency Management committee recommended requiring seismic upgrades for businesses in URM buildings, with possible tax exemptions to offset the costs for property owners.

In 2012, Rose City voters passed a $482 million bond to improve schools, mostly focusing on seismic retrofits. A few years later, the Seismic Rehabilitation Grant Program provided $125 million to schools and $30 million to emergency services for seismic upgrades. With the help of $600,000 in Federal Emergency Management Agency funds, hundreds of homes have been bolted down.

But these initiatives — and don’t get us started on the state of Oregon bridges and fossil fuel infrastructure — aren’t nearly enough.

Ted Wolf, a freelance writer and a leading advocate for seismic safety in schools, estimates that more than 65 of Portland’s 79 public schools need seismic upgrades. To make that happen schools need more money than what the city and state have provided. Wolf says it would take a major bond measure to raise the money to retrofit all of the city’s K-12 buildings.

“The big concern is who’s going to pay for this,” he says. “The city of Portland does not have the resources to say, ‘we are.’”

As the city and state lurch forward, individuals and citizen groups navigate a shaky landscape on their own.

Laarman built up her emergency stash over three years with supplies like grains, squash and canned fish.

Tony Lamb, an intern at the Bureau of Development Services and an avid backpacker, counts on his wilderness skills to help him, along with a supply of food and water. Faulkner helped form an association to promote preparedness in local schools. Wolf helped organize a network of concerned families called Parents4Preparedness.

“The city and state are not going to be able to be there at the level you think they will be there,” Faulkner tells her neighbors.

“It would be hard to imagine they have all the resources to retrofit the bridges and the roads,” she says. “When the gas is out you can’t fill up your car. There’s so many little things we take for granted that won’t be accessible to us.”

Drawn by the region’s famed livability, thousands of people continue to move to the Cascadia earthquake region every year.

Many come from California, where a long history of quakes has embedded seismic preparedness into public decision making. The Golden State budgeted $10 million in 2016 for a West Coast earthquake early warning system, for example, before President Donald Trump announced he would slash federal funding for the project. The state implemented a seismic standard for schools in the early 20th century.

Do transplants from other states know about Cascadia and the devastation it will wreak on human life and the economy? Many say they knew about the Cascadia quake before relocating. If they survived so long in one earthquake zone, so the logic goes, why not move to another?

“I don’t want to live in fear of something that may or may not happen,” Skowronnek says. “Hey, Mt. Hood could go at any moment too.”

Christian Haggarty moved from the Bay Area to the Pearl District. Earthquakes are a regular occurence in California, he says. “You’re kind of already in that mindset when you’re moving there.”

Haggarty keeps earthquake kits with water and dried food in the car, and feels confident about the brand-new apartment he lives in. “In terms of where I work, he says, “I haven’t given it much thought.”

Jesse Springer, a Portland architect, learned about the quake through word of mouth and reports on OPB. Nevertheless, he moved to Portland from California in 2010. “It didn’t really affect my decision to move at all,” he says. “I grew up in an earthquake zone.”

Dawn Skowronnek, a realtor, developed a nonchalant attitude toward tremors while living in California. Now, she mostly works from home in her relatively earthquake-proof Slabtown apartment. She hasn’t given much thought to the structural integrity of her one-story office building.

“I don’t want to live in fear of something that may or may not happen,” she says. “Hey, Mt. Hood could go at any moment too.”

“I am not the only one to say that the best thing that could happen is for us to have a three to four Richter scale quake,” Laarman says. “No one gets hurt but people feel it and hopefully are moved to action.”

A staple of conversation around office water coolers and dinner parties, the Cascadia quake generates a wide variety of responses from terror to black humor to pragmatism.

A select few haven’t heard about the quake at all. Edward Robertson, a security guard, moved from Cleveland in 2015. He first learned about the earthquake when we approached him to ask about it.

He was undaunted. “I’m from Cleveland,” he says. “It would take a lot to scare the hell out of me.”

Laarman, for one, thinks a good scare is just what the region needs. “I am not the only one to say that the best thing that could happen is for us to have a three to four Richter scale quake,” she says. “No one gets hurt but people feel it and hopefully are moved to action.”

According the latest report, from the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, the quake could cause $80 billion of damage in the Portland metro area and kill tens of thousands of people.

The cost incurred by post-quake damage, seismic safety advocates agree, will far exceed the cost of preventing or mitigating damage ahead of time.

Preparedness is also good for the psyche — up to a point.

Faulkner has sifted through the reams of data, organized countless meetings and talked to many of her neighbors. But at some point, she says, the mind needs to rest. “I’ve gotten past the point of being afraid,” she says, “and I’m just curious and in awe.”

To ubscribe to Oregon Business, click here.