How juniper tree harvesting makes business and environmental sense.

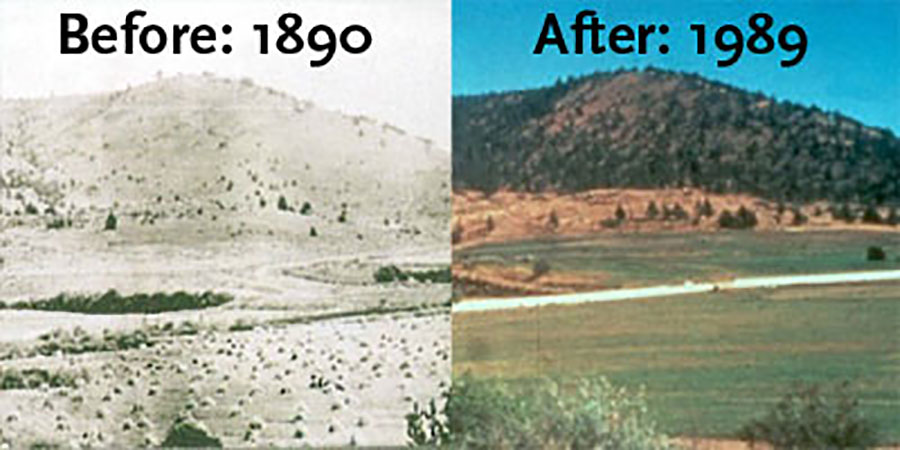

Walking across the expanse of Eastern Oregon 100 years ago would have revealed sprawls of sagebrush and grassland, spotted with the occasional western juniper tree. Today the image is reversed, with those picturesque landscapes often overgrown with the same trees.

A legacy of fire suppression has turned western juniper into a “native invasive,” expanding from 1 million acres at the turn of the 20th century to a staggering 10 million acres across Oregon today.

Western juniper is a thirsty tree, drinking up to 35 gallons of water a day in a high desert ecosystem already plagued by chronic drought. As the trees expand, they crowd out sagebrush and other vegetation, having now consumed as much as 25% of Oregon’s native grasslands. Sage grouse steer clear of any nearby junipers, as the trees provide perches for avian predators and eliminate limited sources of food.

This same pressure is felt by the region’s cattle ranchers, who must constantly fend off encroaching juniper to maintain productive pasture and water resources for their livestock.

The urgent need to remove and manage encroaching juniper has been recognized by a broad and unprecedented coalition of interests. In 2013 the Western Juniper Alliance was formed, convening environmental groups, businesses, ranchers, government officials, universities, and state and federal agencies to chart a different future for Oregon’s rangelands.

Led by Sustainable Northwest, the venture has two core goals: Remove encroaching juniper to restore rangeland health, and create good-paying rural jobs in Oregon’s logging and manufacturing sectors.

The second goal is made possible by the unique and underappreciated attributes of western juniper. It thrives in both the windy and frigid snows of winter and the hot, dry days of summer.

It’s also a hard wood that responds well to moisture, and is naturally rot and decay resistant.

What makes juniper such a natural survivor also makes it an outstanding green-building product. In outdoor applications, it has been proven to last up to 50 years or more for in-ground contact, delivering better performance than cedar and redwood, and at the same or lower price.

This quality is achieved without the chemical treatments common in pressure-treated wood, making it an outstanding option for organic agriculture and in the home-and-garden marketplace.

As a result, a healthy demand has developed for landscaping products including retaining walls, garden beds, fencing, decking and siding. Live-edge slabs are available as tables and desks, and kiln-dried finished wood is appearing in showrooms as cabinetry, butcher-block surfaces, paneling and flooring.

The success of emerging markets has been reflected in the rural Oregon communities manufacturing these products. With a growth in demand, the number of operating juniper sawmills have more than doubled from four in 2015 to 10 small sawmills today.

Lumber sales have increased by 25% for three years in a row, and distribution has expanded beyond Oregon to Washington, Idaho and California. In 2017 the industry received yet another boost when mechanical and durability testing was completed at Oregon State University to make juniper wood products eligible for public procurement and publication in standard industry trade manuals.

Despite this positive progress, the effort is not without its challenges. The availability of and competition for qualified workers in Oregon’s rural communities has hampered the ability to meet market demand due to vacancies in logging, hauling and milling operations.

Investments are needed to train and recruit the next generation of rural-land stewards, and partnerships must be established with the state’s network of workforce-development entities to better publicize and promote employment opportunities.

Western juniper removal and rangeland restoration are also expensive, frequently relying on state and federal funding to leverage private landowner contributions. The results are inconsistencies in the supply chain that must be resolved for long-term predictability.

In response, there is more focus on developing harvesting efficiencies and new markets for the large volume of small-diameter juniper available on the landscape and waste products created at the mills.

Production and marketing partnerships with the private sector and conventional forest-products industry will raise the profitability for juniper loggers, create greater value across the supply chain, reduce disposal costs, and stretch limited state and federal resources for rangeland improvements.

Today Oregon’s western juniper industry supports multiple businesses employing more than 45 direct staff in some of the state’s most isolated rural communities. This number is set to increase in the next two years, along with complementary jobs in the rangeland restoration, distribution and retail sectors.

Significant work is still ahead, but with the help of private-sector investment, the alliance can have a good chance of establishing a self-sustaining western juniper industry in Oregon in the next two years.

Dylan Kruse is director of government affairs and Jordan Zettle is green markets associate at Sustainable Northwest.