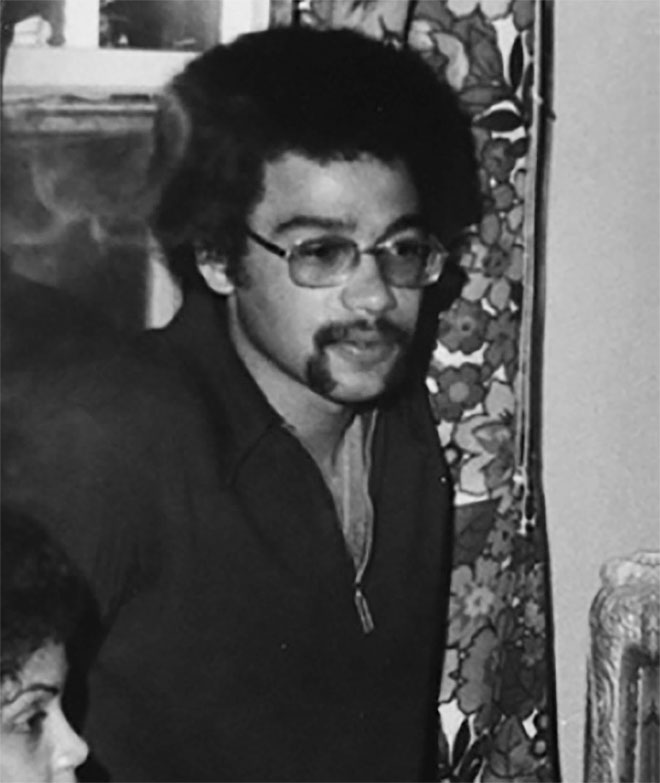

The president and CEO of Legacy Health reflects on formative educational and work experiences.

Later this year, my tenure at Legacy Health will end when I retire.

As my clinical and administrative career begins to wind down, I know the lessons I learned in a grammar school educational experiment played an important role in my success.

I grew up in the inner city of New York, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan commonly known as Harlem. Neither my father nor my mother finished high school, but they had a strong and abiding determination to make sure that all their children at least finished high school and then hopefully went on to college.

When I was in grammar school, the city embarked on an educational experiment that involved administering aptitude tests across the five boroughs.

Based on those test results, students were chosen to be part of a cohort that would move together through grammar school and middle school. My parents found out about the program and, being the oldest of their children, they had me take the test.

Much to my surprise, I was chosen to be part of the cohort.

For the first time in my life, rather than walking to my neighborhood school, I had to learn, as a fourth-grader, to get on the subway and the bus to go to the Upper West Side.

There I first met my new classmates, many of whom were first generation Americans. There were 30 of us in the cohort, and we had three teachers who took us through the grades together.

Respect for diversity and understanding that people came from different cultures and different backgrounds was emphasized as part of our learning process. As a result, we developed close relationships with one another, often spending time in each other’s homes.

Since we lived all over the city, we used the subway to visit our friends on the weekends. Many of us used the subway as a form of weekend recreation, not always paying for it since we quickly learned to jump the turnstiles. We had all of New York City at our beck and call.

My time with the cohort ended when my parents saved enough money to move out to Long Island, but my educational journey had just begun. I subsequently attended Hampton University, a historically black college, where I was fortunate to have a Ford Foundation scholarship, and then went on to medical school at Boston University.

As I reflect on that time, I realize my grammar school experience provided me with some key life lessons. I learned to articulate my point of view and to always ask questions.

I learned to ask, “Why does it have to be this way?” In fact, asking questions became something I excelled at. Doing so sometimes provoked the ire of my supervisors, but most often they were very understanding and indulged my curiosity.

For example, when I was doing my gastroenterology fellowship at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center I thought the process of moving patients in and out was very inefficient.

For example, when I was doing my gastroenterology fellowship at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center I thought the process of moving patients in and out was very inefficient.

I protested loudly to the chief’s secretary about why patients were being inconvenienced. She said if things were so bad, I should speak directly with the Army Surgeon General and let him know my thoughts. I told her to call and make an appointment.

I guess she’d had about enough of my protesting because she made the call.

The next day I was summoned to meet with General Charles Pixley, the highest-ranking officer in the Army Medical Corps. He was very solicitous and understanding, and after listening to me, he offered some insights that I have always remembered.

He said it’s great to ask questions, but more importantly, it’s how you ask them. He added that if things aren’t right, don’t just point out what’s not correct; be prepared to offer up a solution that can make things better.

Gen. Pixley then suggested that I should consider spending equal amounts of time in clinical medicine and administrative medicine.

In clinical medicine, a physician treats one patient at a time. In administrative medicine, a physician can treat cohorts of patients.

I’ve always taken that to heart. I love being a physician, but what I really love is treating the system of health care as a patient, finding ways to make the whole system work better for individual patients.

Looking back, I realize I am fortunate to have been part of that grammar school educational experiment. I was taught to be curious and to view learning as a pathway to understanding, an approach that has served me well in today’s complex health care landscape.

Looking forward, my hope is that an emphasis on respectful questioning and learning to understand will somehow find its way back into our local and national efforts to improve health care for all.

George Brown is the president and CEO of Legacy Health.