Factories face a skilled-labor shortage. Can the Oregon Manufacturing Innovation Center reinvigorate the trade?

Natasha Allen was a tattoo artist before the night and weekend hours became incompatible with her family life. She needed a career that paid well and let her take care of her children — and one that employed the artistic skills she had spent her life developing.

Then she discovered welding.

Fusing and sculpting metal was not a career she had considered at first. She discovered welding while attending Lower Columbia College and was surprised by the amount of artistry involved in the craft.

“It was a really smooth transition,” says Allen, who is now a tenured welding instructor at Lower Columbia College and a weld process manager at Rightline Equipment. “Ninety percent of welding is comfortability, art and science. I’m a big nerd anyway, so it was easy.”

Allen was the only woman on a 60-person welding floor when she started her job, and she has made it a mission to attract more women and people of color to her profession. She currently serves on 32 advisory boards, many of which are aimed at introducing new people to the trade.

She says battling negative perceptions about welding and manufacturing jobs is a constant challenge for her.

“Welding isn’t the same dirty job your grandfather had where he would come home with black lung. It’s clean, the money’s great and you can take it anywhere,” she says.

In fact, the work is more fun — and much easier — than most people think.

Natasha Allen welding. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Natasha Allen welding. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

“When I first started, I thought I would need all these years of training before I could weld, but welding isn’t that hard to learn. It’s actually super fun and very artistic. All my kids can weld, even my 5-year-old.”

Three of the boards she sits on are part of the Oregon Manufacturing Innovation Center (OMIC), a publicly funded manufacturing campus in Scappoose, which held its first-ever in-person class this summer. The center was established in 2017 with $21.5 million in government funds in a bid to make Oregon’s manufacturing sector globally competitive.

Despite COVID-19 setbacks, the center’s mission of making Oregon a manufacturing hub could prove pivotal in the coming years. Stakeholders hope to entice outside companies to set up shop in the state — pumping fresh dollars into Oregon’s economy, which has been slow to recover from the COVID-19 recession.

That would be a “win-win-win” scenario, in the words of OMIC executive director Craig Campell, but it depends on whether Oregon could satisfy the demand for manufacturing labor. The manufacturing industry currently faces a dire, nationwide shortage of skilled labor, which creates opportunity as the global economy rebuilds.

The success or failure of OMIC’s mission could rest on the ability of its new Training Center — which had its first-ever graduates this summer — to collaborate with OMIC’s industry partners and train the next generation of skilled manufacturing workers.

OMIC is modeled after the University of Sheffield Advanced Manufacturing Research Center in England, which brings industry, higher education and government entities under one roof to collaborate with one another on joint ventures, address industry-wide challenges and establish a strong local employee pipeline through its training center.

“It’s essential to reach people who might not normally be interested in manufacturing,” says OMIC training director Andrew Lattanner. “When people think of manufacturing, the perception is that it’s the three Ds: dirty, dark and dangerous. But that isn’t the way things are anymore.”

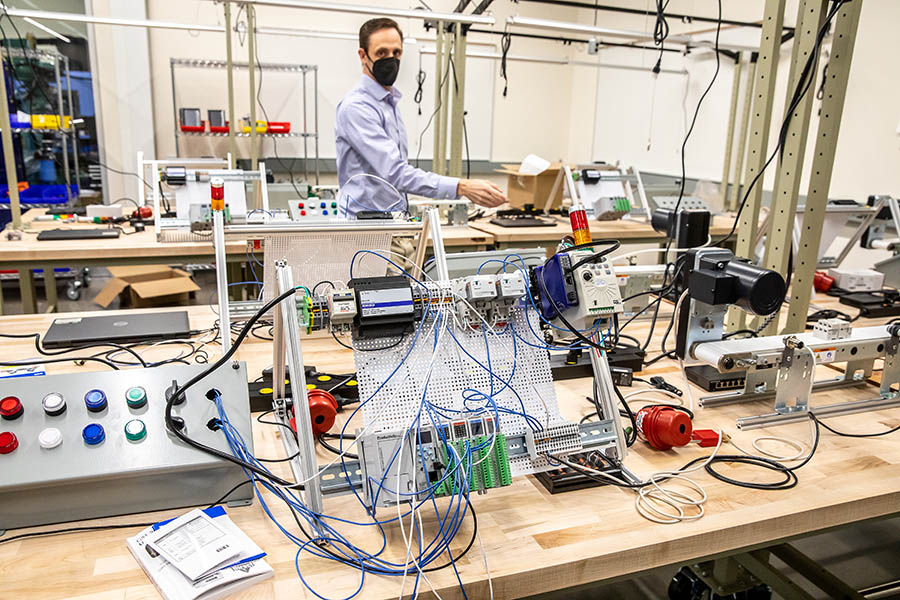

OMIC’s training center is operated by Portland Community College. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

OMIC’s training center is operated by Portland Community College. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

The LEED silver-certified training center building, operated by Portland Community College, is meant to re-create the conditions of a modern manufacturing facility. The walls, mostly translucent glass windows, allow anyone walking through the building to see the colorful robotic arms, microchip soldering stations and metallurgy machines, which require the user to be able to code.

The popular perception of manufacturing jobs is that they are disappearing, with robots and cheaper, overseas labor taking the place of the American factory worker. That’s true in some manufacturing sectors. This year workers at Portland’s Nabisco bakery started a national strike against parent company Mondelēz International, spurred in part by the company’s decision to close U.S. factories and open new ones in Mexico.

But the manufacturing sector is also hurting for workers. According to a May report by multinational consultancy firm Deloitte, labor shortages in manufacturing will represent 2.1 million jobs by 2030 and $1 trillion in lost revenue.

The job losses can partly be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic. In March of 2020, a survey conducted by the National Association of Manufacturers found 53.1% of manufacturers changed their operations due to the pandemic and 35.5% faced supply-chain disruptions.

And even before the pandemic, manufacturing employers were struggling to staff up. A study released by the National Association of Manufacturers in 2018 estimated 2.4 million manufacturing jobs could go unfilled between 2018 and 2028.

Training director Andrew Lattanner leads a tour of an electronics classroom. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Training director Andrew Lattanner leads a tour of an electronics classroom. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Although robots and automation now play a larger role on the manufacturing floor, most require human assistance. Increased reliance on technology has made manufacturing work more skill intensive and, in many cases, even harder to outsource to other countries.

“What we hear from employers is that they want people who can run a machine and program the machine, and ideally be able to do that for more than one machine,” says Lattanner.

The Deloitte study concluded that diversity, equity and inclusion work will be essential to growing the manufacturing workforce.

“Most shops that were around when I started wouldn’t even interview females, be it fears of sexual harassment or fear of skill level, or the perception that women weren’t capable of doing the job,” says Allen. “The industry is still driven by cis white males. One of my goals is to mentor women in trade programs.”

Ever since she became welding process manager at Rightline, Allen says there has been a “huge shift” in the amount of diversity in the workplace. Now 12 women work on the floor with her. Granted, the company has grown from 60 to 300 people since then, and Allen says more work needs to be done.

Allen currently serves on the OMIC Training Center’s Joint Apprenticeship Training Committee, and works to get young people interested. She conducts outreach to high schoolers, where she brings along a virtual reality welding simulator. The system is designed to mimic the welding experience as closely as possible, including the force required to maintain control of the equipment.

“Between seventh and ninth grade is when studies show girls start getting pushed away from the sciences, so we try to go after them then,” says Allen, who says trying out the machines and realizing they are capable is a critical outreach component. “They try it out and say to themselves, ‘Hey, I could do this,’ and ‘Hey, how much do these guys make again?’”

For a younger generation rethinking the massive debt that can follow a traditional college education, as well as people looking to reenter the labor force after COVID-19, Allen says programs like OMIC are better suited for many people’s financial and family futures.

Students of the hands-on learning facility can tailor their own program to fit with their desired job. For students with existing jobs, family obligations and other logistical challenges, the center employs student success coaches, who work with students on a case-by-case basis to tailor their education around their schedules.

This flexibility reflects another shifting reality of manufacturing work. An April report by human resource software company Ascentis, titled “How Flexible Scheduling Is Transforming Manufacturing,” found manufacturers are taking notice of the flexible scheduling trend by introducing task-oriented work schedules and staggered shifts to accommodate workers.

Basing their programming on feedback from industry partners is at the heart of OMIC’s educational philosophy.

Andrew Lattanner, training director at OMIC, beneath the facility’s overhead crane. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Andrew Lattanner, training director at OMIC, beneath the facility’s overhead crane. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Outside the training facility, Lattanner demonstrates an educational crane operating system, which was installed at the urging of the center’s Joint Apprenticeship Training Committee; a group of regional industrial employers said crane operation was something they valued highly in a potential employee. The system was installed despite logistical challenges, including the fact that putting the crane system indoors wasn’t possible. The fact that the skill was necessary to the center’s partner meant it was a necessary addition to the facility.

OMIC is divided into two sister facilities: the Training Center, where students learn the latest in machinery and mechatronics skills from industry professionals, and the Research and Development Center, where manufacturing companies can come together to work on joint projects with one another, using interns and apprentices already familiar with the technology.

Partnership with OMIC can take several forms. Partnerships with the Training Center are based around the company’s individual needs. Some partners engage in hiring and on-ramping events in high schools and colleges. Others help develop curriculum, apprenticeship and internship opportunities. Other companies serve in advisory roles, providing input into the mechatronics program or participating in Portland Community College advisory committees. Still others have supported the center through equipment donations and financial contributions.

Companies that hold memberships to OMIC R&D contribute dues, equipment and resources in exchange for participation in the selection and development of research projects.

Companies partner with OMIC to perform product research and development. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Companies partner with OMIC to perform product research and development. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

In addition to accessing the hiring pipeline, companies come to OMIC to work with one another and address common challenges, as well as to get access to the latest research developed at the facility.

For now OMIC’s specialty is additive manufacturing.

Instead of manufacturing where parts are made from shearing off sections from a larger whole (called subtractive manufacturing), additive manufacturing consists of making a part from the ground up with moldable material — like a 3D printer.

“Subtractive manufacturing [is like] baking a huge brick of cake and carving a wedding cake from it. Additive manufacturing is putting that cake together from the bottom up, one layer at a time,” says Joshua Koch, business development manager at the OMIC Research and Development Center.

Hosted by the Oregon Institute of Technology, OMIC R&D has already been up and running for three years. In August the R&D facility broke ground on a new site dedicated solely to additive manufacturing, scheduled to open in 2022.

Joshua Koch, OMIC’s business development manager, beside a massive 3D printer. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Joshua Koch, OMIC’s business development manager, beside a massive 3D printer. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

The research center is currently on the forefront of additive manufacturing. The facility currently operates a GEFERTEC ARC605 3D printer, capable of printing metal parts. Its projects included the creation of a Daimler truck part using a 500-ton molding press injection —one of the largest parts ever created by a 3D printer.

“Industry was afraid to do this. The thought was, ‘There’s no way 3D-printed parts could ever be as reliable as regular parts,’” says Koch. “We plan on making 1,500-ton molding press injections and showing manufacturers how to really take advantage of 3D manufacturing processes to make their facilities more competitive.”

Cross-pollination between multinational corporations and with local industry partners is another way the center plans to advance Oregon’s manufacturing industry. “We want to be the place for additive manufacturing,” says Campbell. “Local companies want to take the next step with technology, but it can be a little scary. You might say, ‘I want to put additives in my products,’ but you might not know what process is needed. Businesses that have done it before can help.”

As time goes on, more collaboration between the training center and R&D center is expected. The plan is to have students come over and work directly with industry partners on the developmental side of the industry, making students more effective and more valuable to employers with their innovative thinking.

“When students enter the workforce, they are going to have that R&D mindset of ‘How can we do this thing better?’” says Koch.

Like the manufacturing industry itself, OMIC has had setbacks in its mission to turn Columbia County into a manufacturing hub. The center’s dream of luring an outside manufacturer to Oregon was nearly realized when Texas-based industrial equipment manufacturer OSG USA Inc. announced it would open a new facility across the street from the OMIC campus in 2019.

The plan was scrapped because of COVID-19 complications.

But Campbell anticipates more opportunities. The area around the center has 750 acres of shovel-ready industrial land. Some sites have roads and plumbing already built. The center also applied for one of the Biden administration’s Build Back Better grants to build a third OMIC facility, a business development center, to serve as an incubator for new companies.

For Allen, an industry partner Lattanner describes as an OMIC “super contributor,” the facility is a chance to do things differently. Her time balancing two jobs and family life means she understands what it will take to draw new people to manufacturing jobs.

But for her, the skill level of OMIC students means companies would be wise to accommodate them.

“Plenty of people are at home rethinking their career options. Part of this program we all understand is knowing we’re going to get a killer employee who’s super smart — someone who is going to walk out of this with all these certifications and all this knowledge. But we also recognize they’re human and we have to work with that as well,” she says.

“It’s a cooperative thing,” Allen says. “We all have to do it together.”