The Department of Defense is by far and away the federal government’s biggest spender — but few of those dollars flow into Oregon. Some trade groups are looking to bump up those numbers.

Shane Steinke moved to Bend last year with a mission: to get more Department of Defense dollars to Oregon companies.

Last year the Oregon Manufacturing Extension Partnership — a not-for-profit funded with a combination of federal, state and private dollars — hired Steinke as a principal consultant to get more Oregon manufacturers into the defense supply chain.

Less than 1% of Oregon’s gross domestic product comes from DOD contracts, according to an analysis by the federal Office of Economic Adjustment breaking down military spending by state. By that measure, Oregon is dead last among U.S. states and 40th in terms of the amount of DOD spending in the state.

In many ways that’s unsurprising. Following the closure of the Umatilla Chemical Weapons Depot — a U.S. Army installation in Eastern Oregon — in 2012, the state doesn’t have any active military bases or installations. And with the exception of Boeing, which opened a facility in Gresham in 2012, the DOD’s largest contractors are situated elsewhere.

“There are definitely places where there are sort of ecosystems,” says Steinke, who served in the Air Force for 23 years before he was hired by OMEP. “There are huge ecosystems in and around places like Norfolk, Virginia — lots of shipbuilding, lots of subcontractors, lots of bases. Those places naturally attract a lot of companies that end up either in, or adjacent to, defense manufacturing.”

Steinke says his job isn’t to lobby the DOD on behalf of Oregon contractors. Instead, he says he works directly with businesses and to connect them with resources that will help them land more federal contracts.

For example, the Defense Logistics Agency runs a series of procurement technical assistance centers across the country, and sometimes OMEP will refer clients to those centers to get a sense of first steps.

“In other cases, we have companies that are maybe already in the [defense] supply chain, and will work with them through kind of our standard portfolio of services to make them a better supplier, improve their margins, help them increase efficiency or productivity so that they can either meet targets or meet targets with more margin,” Steinke says. “That’s, quite frankly, what they’re looking for. They’re looking for some impact on their bottom line.”

Not everybody would say the lack of DOD dollars flowing into Oregon is a bad thing, notes Rick Evans, executive director of the Organization for Economic Initiatives’ Government Contract Assistance Programs.

Evans’ nonprofit was founded in 1986 amid a political push to make defense contracting more competitive and more accessible to small business. He notes that in the past he’s organized conferences on military contracting — and they were met with protests.

But Evans says there are more defense contractors in the state than many Oregonians realize.

The Pentagon is by far the biggest spender in the federal government, and even if Oregon gets less military money than other states, it still gets a lot, with $1.7 billion in military funds flowing into Oregon every year.

Most are subcontractors, working under the wings of bigger defense industry players. And most, Evans says, “just quietly do their jobs.”

But the state’s defense industry also includes some big-in-their-niche players, like McMinnville’s Northwest UAV. The company makes propulsion systems for unmanned aerial vehicles — better known as aerial drones.

Jeff Ratcliffe, the company’s senior director of business development services, says NWUAV is the largest manufacturer of UAV propulsion systems in the world, having shipped more than 18,000 systems.

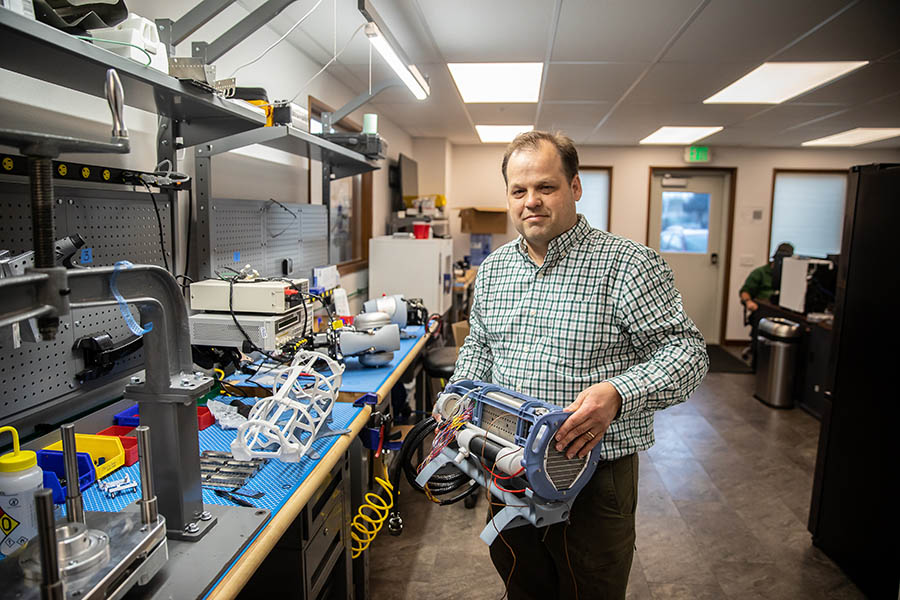

Jeff Ratcliffe, chief technical officer at Northwest UAV Propulsion Systems in McMinnville, holding a hydrogen fuel cell stack. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Jeff Ratcliffe, chief technical officer at Northwest UAV Propulsion Systems in McMinnville, holding a hydrogen fuel cell stack. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

The company’s customers are a “who’s who of the defense aircraft industry,” he says, though the only one he named is Boeing Insitu. (Ratcliffe also worked at Insitu in 2005 in early days before its acquisition by Boeing in 2009.)

Kate Kanapeaux, vice president and acting executive director of the Pacific Northwest Defense Coalition, notes that most of the state’s military contractors make products for both defense and civilian applications — and that the Pentagon is historically a major investor in research and development of new products.

“Fifty percent of the R&D funding that comes directly from the US government goes through DOD. From duct tape to the internet, those were all funded through the Department of Defense,” Kanapeaux says.

Dale Neubauer’s Bend-based company, Blue Moon Designs, sells HeliLadders — a ladder tailored specifically for helicopter mechanics — to clients that include hospitals, fire departments and National Guard units. And the company just inked a $1.6 million deal with the Navy and Marine Corps.

Kanapeaux’s organization — a trade association funded by membership dues — was founded in 2006 by a handful of companies working in the defense space.

Neubauer’s advice to manufacturers looking to get government contracts?

“I don’t want to say enter with caution, but enter with a sense of, you have a lot to learn,” Neubauer says. For example, the Navy’s initial contract offer was for a two-year, fixed-term deal — which wasn’t going to work for his company due to rapid shifts in the supply chain and materials prices.

“I stepped back and said, ‘No, I can’t give you two years. Things are just looking too strange.’ So I gave them 12 months,” Neubauer says.

Navigating the complexity of government contracts is precisely where Steinke hopes to be helpful.

“In some ways, speaking bureaucracy is an art,” Steinke says. “it just kind of comes naturally to me.”

Kanapeaux’s organization was formed with the aim of bringing extant Northwest defense contractors together.

“Really, it was the realization from a few companies that there really was a burgeoning industry supporting defense, and that there was a huge opportunity to come together and to learn from each other,” Kanapeaux says.

For example, her organization recently brought together two companies that make similar but slightly different products, to join forces on seeking contracts. The PNDC also sends Northwest companies to defense-specific trade shows, such as the Association of the United States Army’s Trade Show in Washington, D.C., in mid-October.

That sense of camaraderie has also been key to helping the region’s drone industry flourish, says Ratcliffe, who served as President of the Cascade Chapter of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) through 2020 and is now serving as President Emeritus to the Cascade Chapter as well as on the AUVSI’s Board of Directors.

“This region is really kind of ground zero for small UAV manufacturers and component manufacturers,” Ratcliffe says. “Back in the day, the president of Insitu [Steve Sliwa] had as part of his strategy, ‘I don’t just want to build a great company, I want to build a great ecosystem for this industry.’ And he was very successful with that.”

And Steinke is clear that his interest is not in getting big defense contractors to move to Oregon — but rather to help the companies that are here.

He and Kanapeaux both note that the last two years of stressors to the global supply chain have renewed the focus on all kinds of domestic manufacturing — and that defense manufacturers, which are by necessity located in the United States, can play a key role.

“Really, it’s an exciting time for this with the Department of Defense to focus on innovation with moving to a more U.S.-based supply chain and the Northwest’s manufacturing infrastructure that’s here. I see an opportunity to move the needle,” Kanapeaux says.

Editor’s note: This story has been corrected from an earlier version. The previous version referred to the Oregon Manufacturing Extension Partnership by the wrong name. This version also clarifies Jeff Ratcliffe’s role at Insitu and with Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI). Oregon Business regrets the errors.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.