Male tech workers weigh in on the industry’s gender troubles

It’s a Thursday evening in late February and I’m attending a Technology Association of Oregon event held at OMSI. The theme is ripped-from-the-headlines: “Off the Record: The Women of Technology Panel.”

The lobby in front of the museum’s Empirical Theater is teeming with women who came straight from their offices to nosh on hummus and pita, network with colleagues and hear panelists like Rane Johnson-Stempson, Microsoft Research principal research director, and Jill Steinhour, Adobe’s director of high-tech strategy, talk about leaning in and succeeding in a man-centric industry.

Every woman in the room probably has a compelling story to tell, complete with tales of sexism and bias that range from the unconscious to the overt.

But tonight I’m not here to talk to them. Instead I’m interested in what the men have to say. Of the 165 or so people attending this event less than 15 are male. I ask them all about gender troubles in the workplace. To a man they have the same observation; “I don’t see any sexism. Then again, there aren’t many women in this industry.”

That refrain echoed throughout the interviews I conducted for this article. Men in Oregon’s tech sector work in one of the country’s most forward-looking industries, one that prides itself on meritocracy and disruption. They live in some of the most liberal leaning cities in the country: Portland, Bend, Eugene. Add those two components together and you get a business sector that prides itself on being more collaborative and less competitive than its peers in the rest of the country.

How does it feel to have media’s magnifying glass pointed at them? Surely this isn’t the land of cocky brogrammers. This is Portland (or Wilsonville or Hillsboro or Bend), not San Jose or Mountain View. Things look different here, right?

|

“[The office is] a monastery with everyone |

Yes and no. The Silicon Forest faces the same problems that plague Silicon Valley, but perhaps on a smaller scale.

You don’t have to look too hard to find examples of the inherent sexism that pervades today’s tech industry as a whole. They range from the egregious like Ellen Pao’s high profile lawsuit charging venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers with gender discrimination to the niggling: i.e., Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt and Steve Jobs’ biographer Walter Isaacson constantly interupting fellow panelist U.S. Chief Technology Officer Megan Smith at this year’s SXSW.

Portland has its own national-newsworthy embarrassment. Last summer saw Urban Airship co-founder and CEO Scott Kveton resign over the alleged sexual assault of a former girlfriend. The issue reared its head again earlier this year when Kveton was invited to speak at Ignite Bridgetown during Startup Week. The event was eventually canceled.

Given the negative publicity, it’s not surprising that few companies would allow their male engineers and programmers to speak to the topic of workplace diversity. What companies do want to discuss is how they are working to correct the gender divide, which TechRepublic estimates is 75% male nationally. Intel, which just launched a $300 million Diversity in Technology initiative, declined requests for interviews. Mentor Graphics also opted out.

Puppet Labs sent a polite email outlining its gender equality plans. “My concern is the angle,” said Justin Dorff, Puppet Labs’ PR manager. He expressed concern about participating in an article that didn’t include stories from female employees.

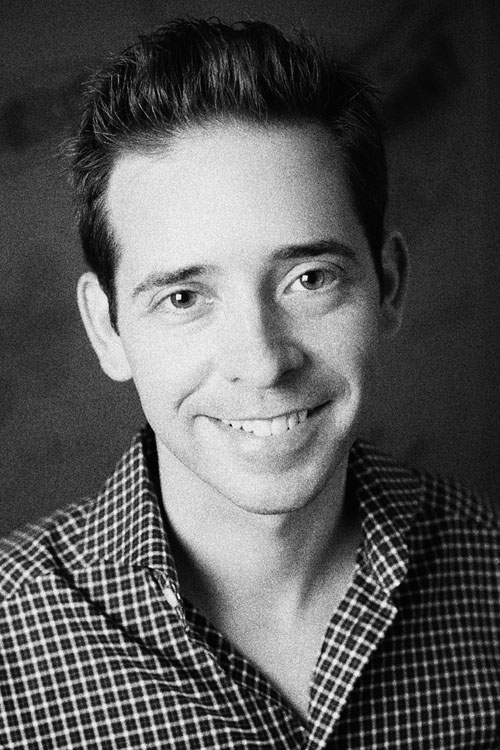

“Why do you want to talk to me,” asked Dylan Tack, director of technology, Metal Toad, a Portland software consulting firm. “Shouldn’t you be asking a woman about this?” Tack, 37, has worked in tech for the past 17 years.

He admits he doesn’t spend a lot of time ruminating on the subject. “If you drew a pie chart of what gets my attention this would be a small sliver,” he says. As part of the company’s hiring team, the biggest slice of Tack’s attention goes to filling Metal Toad’s vacancies with qualified people who fit the corporate culture.

Finding capable employees, male or female, is a problem that plagues the entire sector. As of now there is no official data on how long a tech job stays open before it’s filled, according to Skip Newberry, president, Technology Association of Oregon. But anecdotally, the task appears daunting.

“It’s harder and harder to find any qualified person with the skills and work ethic to fill positions,” says Preston Callicot, CEO, Five Talent Software in Bend. Callicot is well aware of the gender inequality in his field. “It’s an embarrassment,” he says. Of Five Talent Software’s 23 full-time employees and contractors, four are women. Most are client-facing project managers. Callicot describes the development side of the office as a “monastery with everyone plugged into their computers. It feels unbalanced.”

Callicot also notes how the male/female imbalance colors the office vibe right down to the decor. “Our office looks industrial and highly functional,” he says. “You walk in and know right away that this is a software development space. There’s a definite man cave feel.” These small subtleties don’t add up to overt sexual discrimination but instead set the stage for normalizing a heavily-male weighted workplace: a place where unconscious bias can thrive.

Metal Toad also has what one might consider a “man-styled” interior with a foosball table and scooters. Sure there are women who like foosball and scooters but Tack tells of the day that they moved into that new space. “There was so much testosterone- and beer-fueled exuberance that I had a bit of vertigo. It felt like a frat house,” he says. “I’m sure that wouldn’t have happened if there were more women on the staff. It all died down quickly, but I bet other companies with different cultures have that feeling all of the time.”

A friend of mine works as a UI designer at Jive Software, a provider of communication and collaboration software. He sees it a bit differently. The friend wasn’t authorized to speak on the record, so I’m referring to him by a pseudonym. “Robert” looks like a typical Portland hipster, with artful facial hair and well-muscled calves from his daily bike commute. He proudly shares that his ten-person department, user interface design, is 60% men and 40% women. He’s also proud that Jive’s new CEO, Elisa Steele, is a woman.

It’s an attitude that comes from the top. “We’ve had women in leadership positions at Jive for a long time,” states Matt Tucker, Jive’s CTO and co-founder. He points to the fact that five of the company’s ten executives are women. “Still we’re not naive. We know there’s more to do.”

For instance, Robert notes that there are not many women on Jive’s engineering floor. And there is still a boys-will-be-boys mentality that pops up from time to time. He recalls a “locker room-style” conversation about women that he overheard and felt so uncomfortable about that he left the room. “I’m not much of a ‘duder.’ I’ve never identified with or related to the brogrammers,” he says.

When asked if there are disadvantages to working in such a male dominated office, Robert seems at a loss, except for one thing. “It can be hard to find an open stall in the men’s room sometimes.”

Tack, from Metal Toad, can do him one better. “I once visited an office that didn’t even have a women’s bathroom.”

“We’re not naive. We know there’s more to do.”— Matt Tucker |

These small, insidious indignities add up to unconscious or implicit bias. “This is the cutting edge of discrimination law and the next big issue for HR departments,” says Henry Drummonds, a law professor at Lewis & Clark. The role of implicit bias in the workplace will become a more important issue for employers, he says. “But we’re still not sure how this will play out.”

Change will be gradual as the largely male culture is entrenched throughout the industry, even in forward-thinking Oregon, Drummonds says. “We may be on the forefront here. But it’s still an evolutionary process.”

There is precedent for change. Another friend, a software integration engineer for Jeppesen, has seen it firsthand. The 50-year-old grew up in a single parent home with a mother who was both a hardcore feminist and engineer. He started his tech career as a kid in the 80s hacking into the phone line for free long distance calls, a practice known as “phone phreaking.”

“When I was working in Arizona in the late 80s it was definitely an old boys club,” he says. He remembers companies back then starting a sexual harassment education program and getting a lot of pushback in the form of “bitching, moaning and eye rolling.”

The attitude has changed quite a bit since then, says Ted, although he too, was not given permission by Jeppesen to speak on the record. Employees at this company, which specializes in navigational information management for the airline industry, consider the 30-minute sexual harassment training session as just another part of their job, he says.

“In fact, revisiting and reinforcing the topic every year probably makes an impact,” he says. Jeppesen did not return Oregon Business calls for comment.

Ted points to subtle ways Jeppesen tries to normalize women in the workplace, like the motivational posters that decorate hallways and breakrooms. These posters, which illustrate company values like ethics, portray women as equals. Ironically, the posters are more balanced than the actual gender mix. Only six of the 40 employees at the Wilsonville site are women, and one is an administrative assistant. There are no women in his group, Ted says.

Despite the predominantly male staff, Ted insists that the atmosphere is very respectful of women: a good thing as the company is filled with what Ted calls, “manly men who do manly things like build and fly airplanes.” He does however note a slightly different vibe at OSCON, the Open Source Convention held in Portland every year. “There are always pretty, young women working the booths at the show,” he remarks. “I guess sex still sells.”

“It’s frustrating that in such an open, inclusive, |

That tactic may fly behind the scenes at code industry events, but it would appear tone deaf when pitching product to the general public. That’s because women are more likely to buy tablets, laptops and smartphones according to a 2012 study conducted by retailer HSN.

“The tech industry has long been dominated by men, but women are really the powerhouse in the household driving purchase decisions,” Jill Braff, executive VP of digital commerce for HSN, told the digital news stie Mashable in 2012. “Women are highly engaged with the latest and greatest gadgets and technology.”

Today, any industry with an online presence — basically every industry — has tech positions to fill. While the opportunity for implicit bias is always there, a company’s overarching culture may tip the scales in the other direction. Nishant Bhajaria, a product manager for Nike, who has worked for tech companies including Intel and Janrain, explains how the apparel giant differs from some tech startups.

“Most of the engineers in startups are men who are completely plugged in with headphones,” says Bhajaria, 33. “That helps them focus and be productive but may also cause them to be cut off. At Nike, engineers are part of more interactive culture.” That social vibe — coupled with the opportunity for a lateral move — may eventually bring more female engineers into the fold.

Bhajaria, who also works as a career coach, has seen the struggle competent women face in the tech sector. A female friend told him about the time she quietly proposed a solution to a problem at her Silicon Valley startup. She was ignored, but a man loudly restated her idea and was acknowledged. “Sometimes, the start-up culture prizes the person who speaks the loudest,” he says.

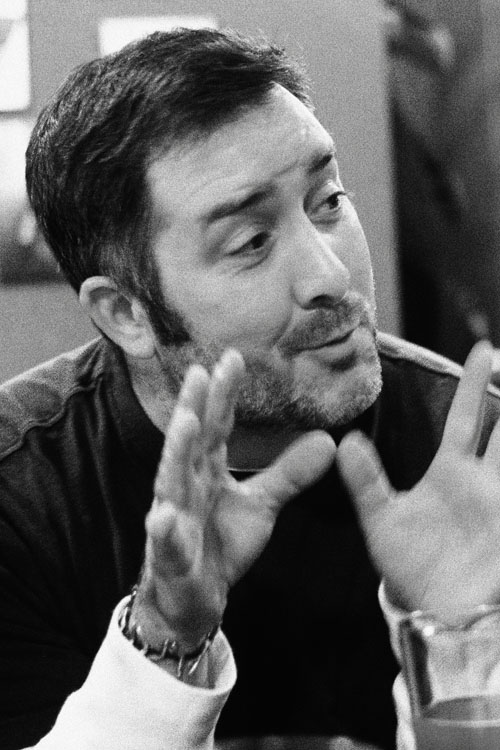

It’s an issue that dogs Rick Turoczy as well. As co-founder and general manager of Portland Incubator Experiment (PIE) 43-year-old Turoczy is the unofficial spokesperson for the Portland tech scene, having worked tirelessly to nurture the sector for the last 20 years. “Identifying a problem and working to fix it is what drives the start-up mentality,” Turoczy says. “It’s frustrating that in such an open, inclusive environment we’re still wrestling with such a basic problem.”

He notes that Portland likes to think of itself as ahead of the curve on this issue but says that, “we’re probably no different than anywhere else.” He points to the fact that PIE averages two women founders in every class, which comes to 10%. “We’ve had some painful conversations on how to solve this problem,” he says, aditting that he’s never intentionally pushed to find female run candidate businesses. “It’s frustrating because everyone is motivated, yet it remains endemic.”

If finding qualified candidates to fill specialized technical positions is hard, locating female ones is like finding “unicorns,” according to Five Talent’s Callicot. Today, big companies like Intel are throwing their financial weight at the problem with hopes of making a difference.

The company’s $300 million Diversity Initiative strives to “achieve full representation of women and under-represented minorities by 2020,” according to a press release. The money will go to building a pipeline of engineers and computer scientists, support hiring and retaining women and funding programs to support more positive representation with the technology and gaming industry.

In time it may, but the pipeline is long. For now, the company’s initiative is generating plenty of water cooler talk. “I have friends at Intel who said they’ve been offered a finder’s fee for women engineers,” says Tack. Intel spokesperson Chelsea Hossaini declined to comment.

Puppet Labs, the fast-growing Portland-based IT automation company, has more than 300 employees, a 28% female/72% male gender split and its share of diversity initiatives. The company offers women’s workshops, sponsorship for women and minorities to their annual user conference and an Unconscious Bias Workshop.

“The latter is a learning session we host at our offices to help make sure Puppet Labs is a respectful and inclusive workplace for everyone,” Dorff says. The sessions start with a video created from a 45-minute presentation by Brian Welle, director of people analytics at Google, on the topic. After watching the video, says Dorff, the group participates in a facilitated talk about the presentation and what is applicable to Puppet Labs.

Will there always be bias in the workplace? Certainly, it’s a problem that’s not going away any time soon. We’re human. We make unconscious micro-judgements about people every day: male or female, young or old, black or white, introvert or extrovert, Ruby programmer or Java. “We are constantly bombarded with social information,” says Barbara Diamond, founder of Diamond Law Training, a Portland-based firm that runs training on implicit bias and microagressions in the workplace. A workforce that incorporates and celebrates these differences would be ideal.

Can men speak for women? Tech entrepreneur turned academic Vivek Wadhwa, one of the loudest voices on the gender inequality issue and co-author of the book Innovating Woman, stopped addressing the subject after he was criticized in February for his tone and message. “I’ve done what I needed to do,” Mr. Wadhwa said in an interview reprinted in the New York Times. “I’m not needed anymore, and I know it.”

“There was so much testosterone- and |

The tech sector may make headway into this issue yet. Its leaders are already disruptors, changing how we work, play and live. Portland, with its collaborative, cooperative, anti-Silicon Valley reputation, sits at the epicenter.

Women continue to chip away at true progress with the help of events like Women in Technology and initiatives from Intel’s program to ChickTech, a nonprofit that tries to get more girls to code. Ellen Pao lost her case against Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, but she promises to advance the cause by drawing attention to the undeniable bias that still exists. “I’m optimistic that there will be change,” says Diamond. “Most people want to see themselves as unbiased. Training and initiatives will help open minds.”

Still it’s mostly men at the top who are driving this change. As Dorff notes, to create real culture change, “you have to get buy in from the entire organization.” For now the average Portland tech worker remains busy at work. They are plugged into the computer; earbuds in, hat on, many are unaware of, or at best, slightly embarrassed by the issue. When they look up the world may look different. Or exactly the same.

EDITOR’S NOTE: It’s a Man’s World

AN OLD STORY

Women have claimed their space in Oregon’s male-dominated businesses with mixed results. Oregon’s manufacturing workforce is only 26% female, according to the Oregon Employment Department. Women make up 17% of the state’s construction labor force and 27% of workers in the transportation sector.

New takes on legacy industries are changing the game — somewhat. About 10% of participants at Oregon Manufacturing Extension Partnership events are women, says Matt Preston, marketing and communications director at ADX Portland, a small maker space. But in his own company, the ratios “are much different than an old school industrial manufacturer.” Of its nine full-time employees four are women, including owner, Kelley Roy; however, only four of the 12 part-time fabricators are women.