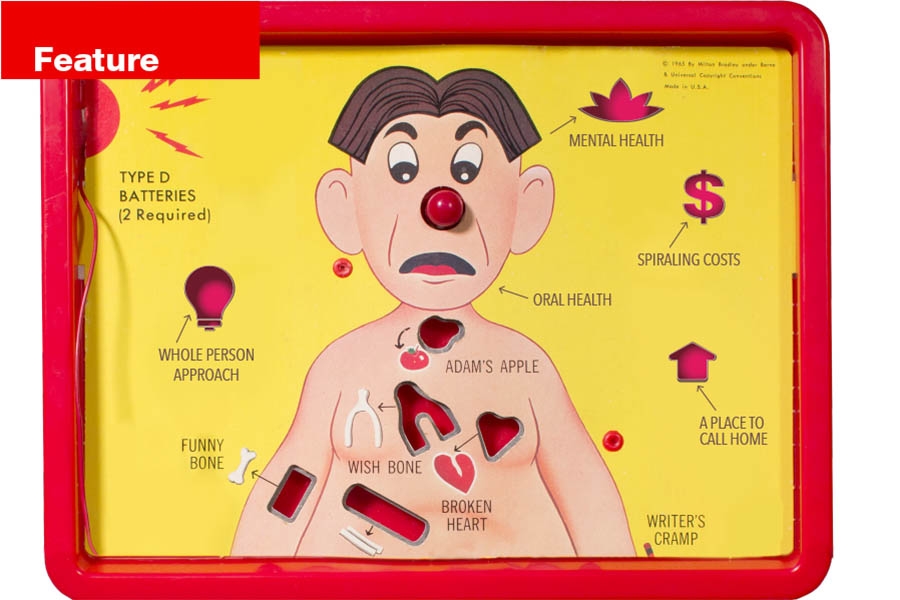

Beset by rising costs and right-wing rhetoric, can Oregon’s bold experiment to revamp coordinated care organizations make the grade?

Instructors teach more than aerobics at the Ashland and Medford YMCAs.

They’re trained community-health workers, guiding members through a variety of concerns, from intensive weight loss to mental-health issues. “They not only provide health, wellness and physical activity but offer incredible social supports,” says Jackson Care Connect CEO Jennifer Lind.“They help members build social networks and friendships.”

People in their programs report better physical health, and the number of those screening positive for depression was cut nearly in half.

All of these positive health outcomes are the result of a partnership between the YMCA and Jackson Care Connect, the coordinated care organization (CCO) serving more than 30,000 Medicaid patients in the Ashland/Medford area.

Under the CCO model, Jackson Care Connect has the flexibility to fund a variety of health-related services like providing a scholarship to the YMCA and tracking members’ attendance. They can also support health training, transforming the YMCA’s staff into a vital part of the medical community.

Launched in 2012, coordinated care organizations were the bold attempt of the Oregon Health Authority, the state agency that oversees health-related programs, to deliver better care to the most vulnerable residents. Seven years later, the experiment is gearing up for its next act.

Known as CCO 2.0, the reboot is a five-year plan to further revamp health care delivery. That first go-round, CCO 1.0 if you will, managed some impressive successes, like those in Ashland and Medford, despite a rocky start. Can CCO 2.0, which faces rising health care costs, shrinking federal dollars and downright hostile presidential rhetoric, go further?

Brainchild of former governor John Kitzhaber, CCO 1.0 was a true innovation. The model was launched under Affordable Care Act provisions. Funded by a generous $1.9 billion federal waiver, which gave Oregon the spending flexibility to conduct this experiment, the first iteration strove to meet health care’s triple-aim goal: improving patient care, boosting community health and controlling cost growth with a local, community-based approach.

“It changed the dynamics of the conversation around how we serve the most vulnerable population out there,” says Eric Hunter, CEO of CareOregon. (CareOregon is a nonprofit insurer providing services to about one-quarter of Oregon Health Plan’s [Medicaid] 1 million members.)

Eric Hunter, CEO of CareOregon Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Eric Hunter, CEO of CareOregon Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Hunter came to Oregon three years ago specifically to work within the CCO model. “This system thinks about whole-person care, not only from the individual perspective but the community perspective,” he says.

“The model is designed to bring everyone to the table with a common sense of purpose and priorities. I haven’t seen that anywhere else.”

CCOs are managed care, but with important differences. Each CCO is locally governed and accountable for access and quality. They receive a budget for behavioral, physical and oral-health services, and have the opportunity to earn bonuses from an incentive pool for meeting or making strides toward 17 benchmarks.

Benchmarks include things like increasing adolescents, well-care visits or boosting the number of colorectal cancer screenings. CCOs also have the flexibility to provide health-related services like critical housing repairs, health classes or workforce development.

That flexibility generated some important innovations.

For instance, in 2016 CareOregon joined five other health care organizations to address Portland’s housing crisis. Their financial commitment helped fund Central City Concern’s $21.5 million Housing Is Health initiative, which added 382 new affordable and workforce housing units in three different locations around the city.

Its Eastside Health Center, also known as the Blackburn Center, is one of only five facilities in North America that integrates clinical services with transitional housing, palliative services and respite housing under one roof. It’s set to open this summer.

Or look at Jackson Care Connect, which is fully owned by CareOregon. It provided $200,000 worth of grants for a variety of community needs from residential addiction treatment for new and expectant mothers to home visits to address school readiness.

It even helped fund “Grandma’s Porch,” a home-safety project that provides assessments, improvements and installations of safety equipment for older adults on limited income and disabled adults of all ages.

“The CCO model is exactly the kind of thing the country needs to be focused on,” says Andy Slavitt, who served as the acting administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under former president Barack Obama. “It’s one of the bright spots in the health care landscape.”

Problems, however, dogged the experiment from the start. Former governor Kitzhaber, the architect of the system, resigned midterm due to an unrelated scandal.

FamilyCare Health, one of the state’s largest CCOs, shut down in December of 2017 after a long-running dispute over reimbursement rates with the Oregon Health Authority. That clash led to sweeping leadership changes at the Oregon Health Authority, which included the firing of director Lynne Saxton and four other department heads.

Incorporating Medicaid expansion presented yet another challenge. Under the Affordable Care Act, Oregonians with household incomes up to 138% of the poverty line were eligible for the insurance. “We didn’t know what that expansion would look like,” recalls Jeremiah Rigsby, CareOregon chief of staff.

Its impact turned out to be enormous. Oregon has seen some of the nation’s most dramatic jumps in Medicaid enrollment under the ACA. Between 2013 and 2017, the average monthly enrollment grew 52% — the 10th-highest increase of all states.

The good news is, thanks to Medicaid expansion, 94% of Oregonians are now insured. The bad news? Now the state had to figure out how to pay for it.

To cover its share of expansion, the Oregon Legislature approved a set of taxes and assessments in 2017. Votes fell largely along party lines. In response, three Republican state legislators launched Measure 101 to repeal those taxes.

The measure was overwhelmingly voted down.

“That was the first time that I know of that health care financing was on the ballot in Oregon,” says Jeremy Vandehey, Oregon Health Authority director of health policy and analytics. “It sent a strong message to the Legislature that Oregonians value health care.”

Bolstered by the bipartisan support and encouraged by new leadership, including the return of Lori Coyner as Medicaid director, Oregon Health Authority and the CCOs are now prepared to build on past successes.

CCO 1.0 made some impressive strides by improving access to primary care, reducing expensive emergency department visits and saving the state an estimated $2.2 billion in avoided health costs.

CCOs under the old model also managed to constrain costs to 3.4% increases year over year, something David Bangsberg, founding dean of OHSU/PSU School of Public Health, calls “really remarkable considering health care costs were going up nearly 10% a year.”

Not a bad start, but it was clearly not enough for Kitzhaber’s taste. “The system is so siloed, so unaccountable, and there’s so much money,” he recently said at an event sponsored by the Oregon Health Forum. “We do not have — in this state, or anywhere in the country — an aligned coordinated delivery model that can get the right services and treatment to the right children and families, in the right amount and at the right time, so that it can make a difference.”

Harsh, but not entirely off the mark.

All the experts agree that to truly transform the health care system, CCO 2.0 needs to go further. Gov. Kate Brown outlined four area of focus: improving and integrating behavioral health; developing a payment system that rewards improvement in health outcomes instead of the volume of services delivered; better addressing of the social determinants of health and health equity issues like housing, food security and transportation; and maintaining sustainable cost growth.

Oh, and for an added degree of difficulty, the state needs to accomplish all of this while the Trump administration seeks to shrink Medicaid.

Trump’s plan, outlined in his 2020 budget, includes allowing states to add the requirement that recipients work to receive benefits, repealing the ACA expansion and moving to block grants, federal monies given in inflexible, fixed-dollar amounts.

These cuts, according to an article in Vox, round out to about $770 billion, an amount which could leave millions more Americans uninsured.

Trump’s negative rhetoric had a chilling effect in Oregon, even before he took office. Going into the 2016 election, the Oregon Health Authority was preparing another ambitious federal waiver, according to CareOregon’s Rigsby.

It wasn’t nearly as generous as that first $1.9 billion ask; but after Trump was elected, officials scaled it back to $1.25 billion for quick approval while Obama was still president.

Oregon Health Authority’s Vandehey, however, stands by the 2017 waiver, calling the stability it provided for CCO 2.0 critical. “There were some one-time, startup funds in that first waiver that were never meant to be extended,” he explains.

Vandehey expects further financial steadiness to come from a recently passed, six-year financing package that extends the existing hospital tax and the insurance premium and managed-care tax.

A tobacco tax, necessary for avoiding a shortfall in 2021-2023, is in the works. Experts think that tax will likely be referred to voters if it passes.

“There’s been remarkable bipartisan support for CCOs,” observes Slavitt. “There’s this narrative that health care is the most politically divisive issue, and that’s true, it is — except for where people live and breathe. That’s where health care is the least political, most personal issue. Oregon has put partisanship aside.”

Gil Muñoz, CEO of Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center, agrees. With 18 clinics, some of them based in schools, Virginia Garcia provides care to 47,000 of Washington and Yamhill counties’ most vulnerable.

More than half of Virginia Garcia’s patients don’t speak English as a primary language, 98% of them live in low-income households, most are insured by Medicaid.

Muñoz says he’s grateful to live and work in Oregon. Yet he’s seen the effects of President Trump’s rhetoric firsthand after his administration proposed expanding the public charge rule to include Medicaid in October 2018.

This expansion means an immigrant may be denied a green card or temporary visa if they used services like Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

“It’s having an impact,” he says. “People who are eligible and qualified to enroll are afraid it could hurt the long-term immigration status of a family member.”

Hunter at CareOregon concurs. “We know for a fact that hundreds of individuals, a lot of them children, are not signing up and getting the preventive care they need to avoid worse health outcomes,” he says. “This is dangerous to a system that is designed to take care of everyone.”

While disruption continues at the federal level, the Oregon Health Authority is drilling deeper into the CCO experiment. This iteration will implement around 40 different policy changes over the next five years. “The overall key message is we’re doubling down and getting much more specific about our expectations for each,” explains Vandehey.

So what does that look like on the ground?

CCOs can expect more stringent access-to-care metrics around behavioral health. This means fully integrating mental health and substance-use disorder services within the CCO. Subcontracting these services out, once a common scenario, will no longer be allowed.

The hope is this will make the CCO much more accountable for member satisfaction and access.

Moving to value-based payments, where CCOs are compensated for positive outcomes as opposed to the volume of services they provide, was an important goal of CCO 1.0 that never really materialized. To make it happen this time, CCO 2.0 sets specific, yearly targets.

In year one, 30% of all payments must be in an approved value-based arrangement; year five sees that number jump to 70%. “We’re expecting very aggressive movement here,” says Vandehey.

A fund has been set up to kickstart more investments around the social determinants of health. The money can be used for things like housing or other nontraditional services that are not health care but still necessary for a population to be healthy.

This investment recognizes that the health care system is only really responsible for about “10% of a person’s health status,” according to Bangsberg. “The rest is genetics and the social and physical environment.”

Jennifer Lind, CEO of Jackson Care Connect. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Jennifer Lind, CEO of Jackson Care Connect. Photo: Jason E. Kaplan

Lind calls the push to address the social determinants of health “validating of the work we’re already doing.” She credits targeted supported housing and short-term housing for Jackson Care Connect’s 15% decrease in emergency department use among individuals with severe and persistent mental illness.

“I’m excited to be part of a community-wide health improvement plan that prioritizes housing,” she says. “One Medicaid CCO can’t build housing, but we can deepen our partnerships with builders and bring in supportive services.”

Funds, in the form of a rewards or shared-savings system, will incentivize sticking to that 3.4% cost containment. “Unless you get a financial reward, there isn’t an incentive to lower costs,” says Vandehey.

Wildly escalating pharmacy costs, however, threaten to topple this experiment. Muñoz explains his concern. “We can do a lot to control expenses for some of our more complex patients, but we have no control over pharmacy costs. They can increase exponentially and take dollars from other parts of the system.”

Drug prices are “front and center in everyone’s mind,” according to Vandehey. He pointed to a new drug that costs $2.1 million per patient and other expensive therapies coming down the pipeline that will make holding increases to the promised 3.4% challenging. “It’s a cost driver. And the state is limited in what we can do.”

Vandehey also notes that pharmacy only represents 10% of the Medicaid spend, which leaves lots of room for efficiencies in the rest of the system. He points to expanded technology and tools that can help CCOs identify inefficiencies in the system, like a poorly managed case or outlier costs.

Oregon Health Authority is drafting rules and awarding the next set of contracts to manage Medicaid. Final decisions will be made in July. This time around, coordinated care organizations have the ability to build on past achievements while pressing forward.

It won’t be easy. And Oregon Health Authority director Patrick Allen knows it. “We see CCO 2.0 as an opportunity to reboot the entire CCO system and reinvigorate health transformation in our state,” he said at a State of Reform conference.

Time will tell if the CCOs can make the grade.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.