Hospitals and insurance companies have embarked on a buying spree. Will new partnerships result in better care — or higher costs?

Cars snake in a slow line around the curves of Portland’s “Pill Hill” each weekday, as patients with complex medical needs seek a coveted parking space at Oregon’s leading teaching hospital. Just 50 miles away in Salem, it’s another story: Open asphalt lots beckon, and hospital officials fret about filling beds and keeping local patients from leaving town for care.

It’s an imbalance echoed across Oregon — and across the country — and driving a shift in health care delivery that started years before the Affordable Care Act went up for its first committee vote. As large urban hospitals face crowded emergency rooms and long waits for specialized procedures, smaller towns are struggling to fill beds, and sometimes to recruit physicians, to communities where the local hospital’s success is a matter of life and death.

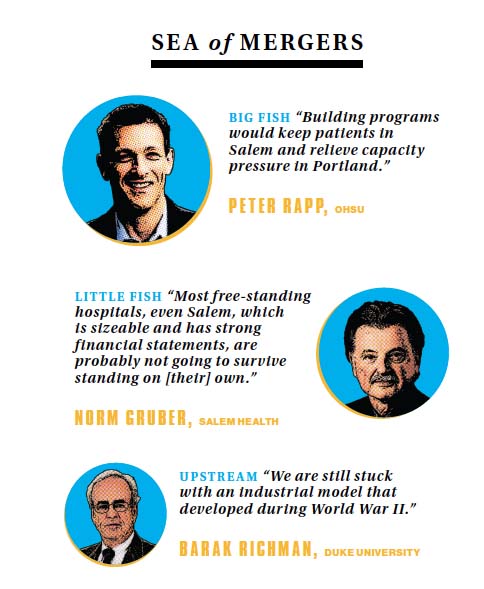

“What does the future look like?” asks Norm Gruber, president and CEO of Salem Health, which operates one of the state’s oldest hospitals. “Most freestanding hospitals, even Salem, which is sizeable and has strong financial statements, are probably not going to survive standing on our own.”

The original Salem General Hospital opened in 1896 in a wooden former schoolhouse, after a funddrive raised $752 to buy five beds and recruit the support of local physicians. Its modern-day successor admits nearly 100,000 people per year to its emergency department, one of the busiest ERs in the state.

It posted a $58.5 million profit in 2014 — echoing a surge in hospital profits across most of the state, thanks to the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, which leaves far fewer poor patients’ bills unpaid. But when patients need treatment for complex medical needs, they often look elsewhere. Keeping care local is key to withstanding market forces that have forced consolidations across the industry, believes Gruber, who led efforts to ally Salem Health with Oregon Health & Science University under a partnership just beginning to take shape.

Gruber is not unique in his thinking. In the Willamette Valley alone, once-independent Silverton Hospital joined the Legacy Health network last year, and Hillsboro’s Tuality Healthcare announced its own still-emerging partnership with OHSU.

Across the state, Ashland Community Hospital mulled joining a California Catholic chain before it ultimately became part of the secular Asante Health network in 2012. The same year, the Idaho-based St. Alphonsus chain, which operates two small eastern Oregon hospitals, became part of the $20.4 billion Michigan-based Trinity Health system after a merger of Catholic health care chains.

Insurance companies are also joining the hospital merger frenzy. For years, only Kaiser Permanente, which fully integrates insurance with provision of health care, and Providence Health, which operates closely related but separate health plans and hospitals, combined hospitals and insurance in Oregon.

Now fast-growing Zoom+ has started selling insurance based around its network of storefront medical clinics. Portland-based hospital Legacy Health and Eugene-based PacificSource Health Plans are seeking the state’s OK to create a regional health plan through a joint venture.

An insurance company integrated with hospitals and clinics could quickly share all of a patient’s medical information with each doctor or nurse that patient encounters, and use data analysis to look for red flags that could indicate worsening health, says Peter Rapp, executive director of OHSU Healthcare. The holy grail: using big data analytics to save money and save lives.

“Providence and Kaiser have shown the value of owning both pieces of the equation,” Rapp says, adding that OHSU and Salem Health have been looking for health plan partnerships, but many of Oregon’s independent insurers are wary of being acquired.

“We have to find a way to coordinate resources differently, to be as good, from a patient’s point of view, as Kaiser or Providence. We are confident there’s opportunity there,” he says. “It’s a very creative time for health care. There’s a whole spectrum of new partnerships emerging.”

But even as industry insiders tout the benefits of streamlining and consolidating health care within fast-growing chains, a backlash is mounting. Consolidation may boost hospitals’ bottom lines, but studies have repeatedly shown that it also pushes up the prices that patients and insurance companies pay.

With faith-based chains among the largest health care organizations in the Pacifi c Northwest, some communities fear that aligning with a larger network could reduce access to local reproductive care. Some critics go further, arguing that building health systems around hospitals is thinking too small at a time when the entire health care system needs to be reinvented.

“We need a vision of what health care can be in the 21st century,” says Barak Richman, a professor of law at Duke University in North Carolina who studies health care policy and sees consolidation as the wrong approach. Mergers raise health-care costs and reduce competition without yielding the benefi ts they so often claim, he argues. “We are still stuck with an industrial model that developed during World War II. We need to embrace an innovative strategy, a new model for hospitals.”

Rapp disagrees with Richman’s assessment, and sees Oregon Health & Science University’s partnerships with Salem Hospital and Tuality Healthcare in Hillsboro as emblematic of a new approach.

OHSU’s costs and medical charges are among the highest in the state. High costs are common nationwide among academic medical centers, which treat more complex illnesses than community-based hospitals — and which must maintain expensive buildings and equipment, while training future generations of doctors.

Though it has expanded its clinics and offices along Portland’s South Waterfront, OHSU’s hilltop hospital is also landlocked. Yet its team of well-regarded surgeons and physicians lure patients from across the region seeking specialized care for diffi cult ailments. The hospital is bursting at its seams.

“OHSU was full, and we had to explore whether OHSU would keep getting bigger,” Rapp says. By partnering with other hospitals, the state-chartered institution saw an opportunity to grow its statewide influence without crowding more resources into its overstuffed campus.

At the same time as Rapp’s team was hunting for partners, Salem Health’s board of trustees had started looking for a larger institution to affiliate with. Rapp saw the partnership as a win-win opportunity.

“Building programs in Salem would keep patients in Salem and relieve capacity pressure in Portland,” he says. “It was a better use of buildings and people. And the costs per admission in Salem are materially less than at OHSU, where our programs are designed for high-intensity care in a teaching environment.” The partnership will free beds at OHSU for sicker patients who today might have to seek care in Seattle or San Francisco, Rapp says.

Most alliances between hospitals are pure mergers or acquisitions, but OHSU’s status as a quasi-governmental agency made matters more complex. It created subsidiary OHSU Partners to merge Salem Health’s finances with those of its own clinical efforts. Technically, both OHSU and Salem Health are separate institutions — but their clinical services are managed jointly by OHSU Partners, with Rapp acting as CEO and Gruber as president.

Though OHSU and Salem are merging finances, officials emphasize that both hospitals are financially profitable — and that the partnership they are forging is focused on improving care, first and foremost.

Both say their relationship will improve access to care across the system. The merger became formal on Nov. 16, and both institutions are still weaving their operations together.

It takes a networked system to care for a patient from diagnosis through treatment and beyond, Gruber says.

“The landscape in health care is changing. The term people throw around is ‘clinical integration.’ The American health care system is fragmented, and that can be a problem for patients. They can’t get an appointment one place, they have three different doctors looking at them in three different ways, not talking to each other. We want to create systems of health care in ways that don’t allow the patient to fall between the cracks. We call it ‘womb to the tomb.’”

When Silverton Hospital decided to join the Legacy Health system, that “womb-to-tomb” approach was part of the equation — but so was money, says Silverton Health board chairwoman Gayle Goschie.

At a time when Oregon’s Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion is driving strong hospital profits, Silverton Hospital posted a $1.6 million net loss in 2014, and a $3.2 million loss the year before. Costly electronic billing systems put the hospital in the red, and it has struggled to fill more than half its beds.

Silverton Health’s board spent several years considering its options and holding town-hall community meetings before opting to join Legacy Health. Goshie cites “efficiencies in the business side of health care,” including volumepurchasing discounts and access to Legacy’s other resources, as compelling factors behind the merger.

“So many advantages,” Goschie adds, noting that like Salem Hospital, Silverton will be able to draw on the expertise of its new, larger partner to treat more patients close to home by bringing specialized services to town as needed.

Yet Silverton chose to partner with Legacy only after months of negotiating with another Portland-based chain, Providence Health. In community meetings during those discussions, residents spoke up about concern that affiliating with Providence, a Catholic nonprofit, might force their secular health care system to restrict reproductive and end-of-life care. Goschie and others associated with Silverton have declined to comment on those concerns.

“We’ve been a secular hospital for nearly 100 years, and are concerned about reproductive rights, contraception, tubal ligation and physician counseling on death and dying issues — none of which is allowed in any of the Providence hospitals,” a Silverton resident told the Lund Report, which covers Oregon health care policy. Local media repeated similar worries.

“We looked at a surprisingly large number of systems and alternatives to grow health care in our communities,” Goschie says. “We’ve partnered with a local independent system that recognizes the advantages that collaboration and independence bring to progressive ventures.”

When they merged on May 31, 2016, Legacy agreed to an eight-year plan to invest more than $60 million in Silverton. Ashland Community Hospital — which nearly joined California’s Dignity Health, a different Catholic chain, before instead aligning with Asante in 2014 — faced financial pressures of its own. CEO Sheila Clough told local media that joining a larger chain has allowed her hospital to lift a pay freeze and put it on track to report its first profits in years.

And Tuality Healthcare, which is negotiating to join OHSU Partners alongside Salem Health, has skated by with razor-thin profit margins for years. “They have economic stress, and that’s one reason to join a bigger system, even if it is not our reason,” Gruber says. “In rural areas and in urban areas, these smaller hospitals have a tough time.”

Profits climb, charity care declines

Nearly all of Oregon’s hospitals are nonprofits, and the tax breaks they get for doing good are coming under new scrutiny.

Gina Binole, spokeswoman for Service Employees International Union Local 49, says hospitals have seen a remarkable rise in profits since the Affordable Care Act took effect — “particularly when you play out that profit against poor people seeking health care in general, and most unfortunately, poor people who work for these very institutions.”

Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act, Oregon’s hospitals routinely reported razor-thin profits, which they blamed in part on the cost of caring for the uninsured. “Charity care” — write-offs for prescriptions, procedures and appointments made by people too poor to pay their bills — reached its peak in 2013, when Oregon’s hospitals said they had to write off $845.9 million in these expenses.

The next year, hundreds of thousands of people were added to the health insurance roles, either through Medicaid-funded coordinated care organizations or through insurance market enrollments. Charity care spending fell by more than half, to $392 million in 2014 — the most recent year available.

That shift helped SEIU gain the moral high ground when negotiating with leaders of PeaceHealth’s hospitals in Eugene and Springfield. The union argued that cafeteria workers and janitors struggled to make ends meet—even in an era of record profits. In April workers ratified a contract that will raise pay by an average of 21% over the next three years.

Sister Andrea Nenzel, who sits on PeaceHealth’s board, says it’s fair to consider wages when assessing hospitals. “We want to be paying a living wage to even our lowestpaid employees.” But she also notes that today’s profit spike may be fleeting, and hospitals face new costs even as charitable spending drops.

“Look at the IT infrastructure we’ve had to add. The financial world has changed dramatically, which affects investments and how we make investments. There are changes to the insurance world. The complications we have to deal with are geometrically different than in the past,” she says.

But the IRS is taking a closer look, according to a briefing in Becker’s Hospital CFO, a publication that covers hospital finances. Federal tax officials are reviewing the rules for charitable hospitals this year, and could start fining institutions that are benefiting from tax breaks without justifying their benefit to the community.

In Josephine County, tax collectors have already ruled that sometimes a profitable nonprofit does not deserve a financial break. Last year that county told the Asante Health hospital chain that it would have to pay property taxes on clinics that did not provide significant charitable care. SEIU estimates that in Multnomah County alone, major hospital chains could be saving as much as $26 million a year on property taxes because of their exempt status.

Binole says SEIU will be eyeing other tax-exempt hospitals in the coming months and years — especially as executive pay climbs and charitable spending shrinks.

Richmond, the Duke Law professor who studies hospital finances, cautions that these savings for hospitals rarely benefit patients or insurance companies. “The end result is never better prices for consumers,” he says. “Better purchasing power? Sure, maybe they get pipettes at a cheaper rate. There is a real need for integrated delivery systems that improve efficiencies, but that’s not what we see with hospital mergers. Instead, you see prices go up.”

Richman cites his own published work, as well as numerous studies, which have found that hospital mergers and acquisitions may help health care organizations stay in the black — but they also push up costs to consumers and to insurance companies. These results hold true across for-profit and nonprofit chains, in rural and urban settings.

The largest analysis of hospital rates, published in December by Yale University and the London School of Economics, found that in cities with a single hospital chain, private insurance pays 15% more than in cities where at least four hospitals compete, after adjusting for differences between communities.

Richman sees the push to merge as a sign that leaders across the country are still not thinking big enough.

“Part of the problem is that we still reimburse health care in a screwy way,” Richman says. “It’s very hard to pay for people getting preventive care that actually saves money down the road. We reimburse based on cost, not on value. If a community hospital is not doing a lot of expensive procedures, it may be creating enormous value and not getting enough revenue. That may require rethinking how we pay for hospitals and care. You really want these local hospitals to find ways to provide care that is affordable. And the delivery system is in need of reform.”

Nearly a century of economic theory and a robust collection of studies suggest that the risk of overconsolidation is greater than the benefits — at least to consumers. “It is true that collaborations across hospitals, especially academic medical centers and community hospitals, can create a certain continuity of care that can be very valuable. But this never requires common ownership,” Richman says.

Advocates of hospital mergers seem to speak a different language and see the world from a different point of view. With the fledgling partnerships in Oregon, it’s too early to say how medical prices will shift — and it’s not an issue hospital leaders seem focused on.

Salem Health’s Gruber disagrees with the notion that aligning will necessarily raise prices, and says that a push to improve patient care is driving hospital consolidation — not a move for financial gain.

“The strength of this community hospital and OHSU coming together is not designed to subsidize one or the other; it’s to develop a system in the best interest of the whole,” Gruber says. “The measure of our success is whether you are getting more and better services closer to home, in a more affordable way.”

Rapp notes that the new OHSU Partners has not even prepared a first budget, let alone developed a long-term financial plan or pricing strategy. “We are doing everything we can to put together one income statement, not multiple statements in pieces. We are not trying to stress about, ‘Did my numbers go up or down?’ We are working hard to develop programs and get people organized.”

He’s more focused on spending than revenue: As a combined system, OHSU Partners hopes to spend less on redundant exams and lab tests, and more on other holistic approaches to care, he says.

The logic of rising private insurance rates makes sense: Consolidation brings hospital chains more market clout when negotiating reimbursements with health plans. As the Affordable Care Act enrolls hundreds of thousands of Oregonians in Medicaid-funded coordinated care organizations, hospitals are seeing profits climb fast — for now. But CCOs dictate the rates they pay, and those payments are not likely to climb as quickly as medical costs in the years ahead. Hospitals will eventually either have to cut the cost of providing care or find other ways to bring in revenue — such as by raising rates with private insurance companies.

Antitrust scholar Richman seems resigned to continuing in the role of Cassandra, crying out his concerns about mergers but never being heard. The Federal Trade Commission, charged with enforcing antirust laws, is outmanned, he says. “There are more mergers than they can police. They are limited to trying to stop the most egregious efforts to create a monopoly.”

More than anything, Richman argues the health care system must be further reformed. Today’s crowded urban teaching hospitals and half-empty community health care centers are fragments of a health system that he would like to see rebuilt — an argument that seems fated to remain unheard in the current political climate.

Meanwhile, the mergers keep coming: Kaufman Hall consulting group predicts that 100 U.S. hospital mergers could go through this year, matching last year’s figure, and on the high end of the past half decade’s typical range of 90 to 100 mergers per year.

It’s all about the strength of big data, big networks and efficiency — as long as gridlock in Washington, D.C., makes Affordable Care Act reforms politically untenable, hospitals will keep responding to what Richman calls a broken market.

Those that don’t merge, Gruber says, could wind up losing out. “Scale will help small hospitals survive. If they don’t merge, it’s like musical chairs. When the music stops, you want a chair to sit on. You don’t want to be standing on your own.”