How Portland has become a crucial hub for fossil fuel exports despite opposition from city government and the local community.

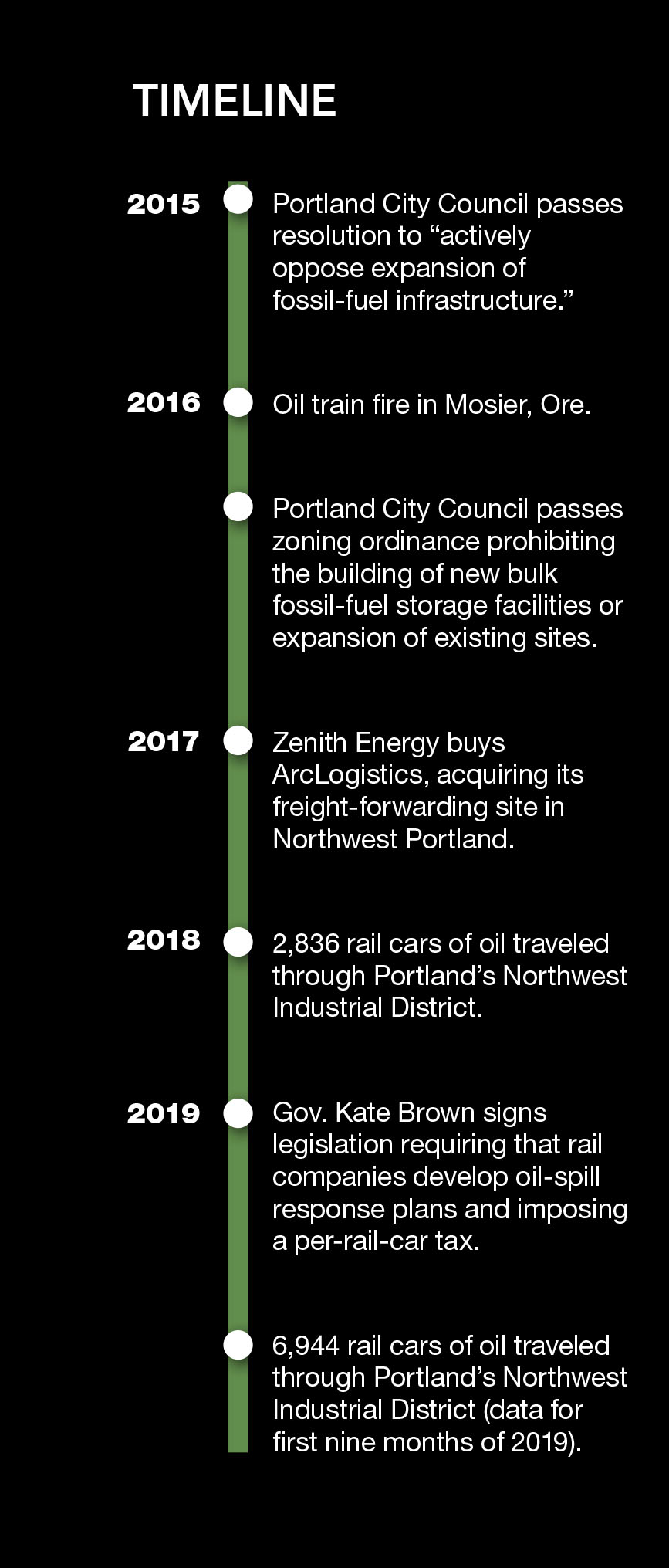

In 2016 the city of Portland passed a zoning ordinance that banned new bulk fossil-fuel storage facilities and prohibited existing facilities from expanding. It added some teeth to a resolution adopted a year earlier that called on the city government to “actively oppose the expansion of fossil-fuel infrastructure.”

The novel approach seemed to put Portland at the vanguard of the national climate movement. “This is the first stone in a green wall across the West Coast,” then Mayor Charlie Hales said shortly after the ordinance passed in late 2016.

The legislation was briefly overturned after an appeal from Portland’s business community, but it ultimately survived legal challenges.

But despite these milestones, and despite vocal support for a clean-energy transition from the city government, Portland has quietly become a crucial hub for the oil industry.

The clash over Keystone XL — the expansion of a large oil pipeline system that transports oil from Canada refineries into the U.S. — is a decade old, and its fate is still up in the air. A separate pipeline project, the Trans Mountain Expansion, would expand oil flows from Alberta to British Columbia for export to Asia. It too has run into stiff resistance.

Year after year, Canada’s oil production has climbed even as pipeline battles raged across the continent. With large pipelines bogged down, more oil has hit the rails.

In 2018 Canada exported an average of 231,000 barrels of oil per day by rail, up from roughly 46,000 per day in 2012, a five-fold increase. Those volumes are on track to grow again in 2019.

Portland is increasingly playing a small but vital role in these shipments.

Zenith Energy, a company backed by two private equity funds, Warburg Pincus and Kelso, operates more than a dozen oil terminals in the U.S. and around the world.

One of those terminals sits in Portland’s Northwest Industrial District along the Willamette River. Zenith Energy acquired the site when it purchased Arc-Logistics, a freight-forwarding company, in late 2017.

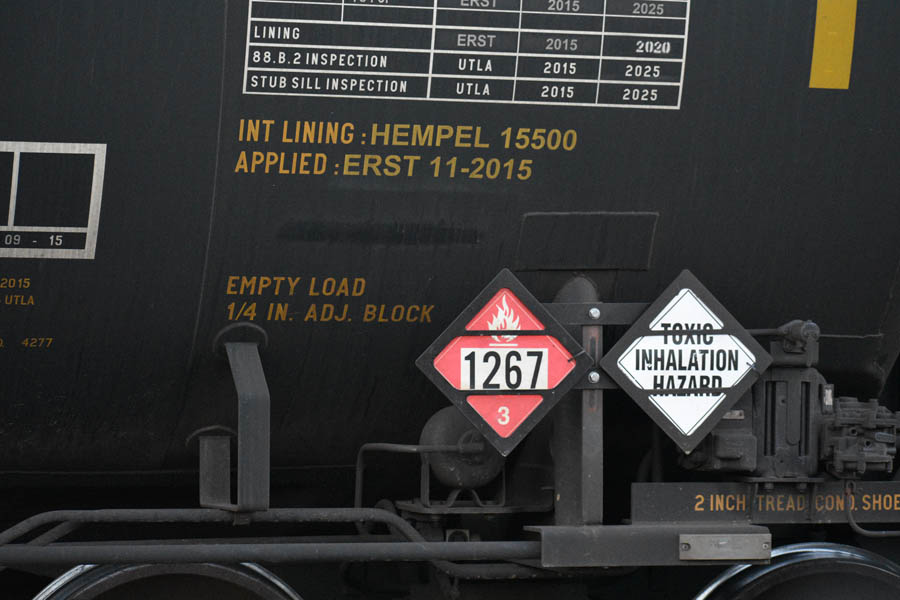

Oil train bound for Zenith Energy terminal Photo: Nick Cunningham

Oil train bound for Zenith Energy terminal Photo: Nick Cunningham

Zenith Energy seemed to fly beneath the radar until Bloomberg News reported in March 2018 that Canadian oil producers had shipped heavy crude to China. The shipment went by rail from Alberta to Portland, where the oil was then loaded onto a ship for export.

At the time, local news picked up on the story, but the shipments seemed sporadic and somewhat insignificant. It wasn’t until a year later that Zenith Energy’s operations sparked a much greater controversy.

Oregon Public Broadcasting reported in February 2019 that the company was expanding its facility so that it could unload more oil. The expansion would allow Zenith Energy to unload 44 rail cars at a time, up from 12 previously.

When news broke that Zenith Energy had essentially decided to turn Portland into a hub for Canadian oil sands exports, environmental groups were incensed.

In April 2019, a local chapter of Extinction Rebellion blocked the railroad tracks at the Zenith Energy terminal in protest. They planted flowers and a garden on the tracks, and sent a letter to the mayor and the city council decrying their inaction. Several of them were arrested.

Photo: Nick Cunningham

Photo: Nick Cunningham

To environmental groups, the 2015 city council resolution and the 2016 zoning ordinance, both of which aimed to block new fossil-fuel infrastructure, were big victories.

But the expansion of Zenith Energy’s terminal was approved by the city prior to those actions, back when the site was owned by another company.

When asked about the new rail system, Zenith Energy disputed the assertion that there was a change in its unloading capacity. “While the new system is more efficient as a result of new technology and better equipment, the terminal can only hold 44 railcars at a time, which is the same number as before the new system was constructed,” says Daniel Wattenburger, a spokesman for Zenith Energy.

“The new railcar system, which includes unloading equipment, improves the safety, efficiency and operations of that capacity.”

While Zenith Energy disputes that its new system constitutes an “expansion,” the one thing that is clear is that oil-by-rail shipments into Portland have surged.

In 2018 an estimated 2,836 railcars full of crude oil entered the Northwest Industrial District on the BNSF rail line that runs through North Portland, according to data from the Oregon Department of Transportation.

That may seem like a sizable number, but in the first nine months of 2019 alone, 6,944 railcars full of crude oil entered Portland. The city is on track to see oil-by-rail shipments more than triple this year.

Zenith declined to comment on rail volumes but confirmed that it receives “most but not all” oil shipments entering Portland on the BNSF line.

A dramatic increase of oil trains entering Portland has raised concerns not just among environmental groups but also with the mayor and city council. Oil trains create “a potential public safety, public health and environmental risk,” Mayor Ted Wheeler said at a community forum on July 15, 2019, at Portland State University.

Oregon is no stranger to train derailments. In June 2016, a train carrying oil from North Dakota’s Bakken shale region derailed in Mosier, spilling roughly 47,000 gallons of oil onto the tracks and the surrounding area.

The oil caught fire and burned into the night, sending a thick column of black smoke into the air.

The derailment was a close call and could have led to a much worse disaster. No injuries were reported, and the Mosier district fire chief reportedly said that if not for the unusually calm winds, part of the town might have been overtaken by fire.

Trains carrying the “1267” placard indicate they are carrying crude oil

Trains carrying the “1267” placard indicate they are carrying crude oil

More recently Portland saw its own close call. On Sept. 7, 2019, a Union Pacific train derailed and collided with support beams at the overpass leading to the Swan Island Industrial Park on North Going Street.

The tank cars were carrying liquefied petroleum gas, an easily ignitable substance. Fortunately, there was no release and no injuries. Union Pacific said the derailment occurred because of a broken rail.

Because of the Mosier derailment, oil-by-rail has been a simmering point of contention in the state Legislature. After several years of failure, Gov. Kate Brown signed into law HB 2209 in July 2019, legislation that requires rail companies moving oil through the state to develop oil-spill response plans.

It also puts a $20 tax on each oil-tank car entering or loaded in Oregon, with the proceeds going to Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality and state fire marshals to help plan for disaster response.

RELATED STORY: Need for better infrastructure, rules frame oil-by-rail discussion

Railroad companies will also be required to carry insurance to cover a “worst case” oil spill; however, the Oregon Legislature chose to define “worst case” as only 15% of a train’s load, which is notably less than the oil spilled in some of the disasters that have already occurred.

In the 2013 Lac-Mégantic derailment in Quebec, 63 tank cars spilled more than 77% of the train’s load, unleashing a cataclysmic explosion that incinerated much of the town and killed 47 people. “‘Worst case’ should probably be an entire train,” Ryan Rittenhouse, with Friends of the Columbia Gorge, says. “I take a little bit of issue with the Orwellian language there.”

There is another danger lurking quietly in the background. The Pacific Northwest is due for a large earthquake, and the Northwest Industrial District is situated in a “liquefaction zone,” which means that during an earthquake, soil can take on the characteristics of a liquid.

On YouTube, there are widely shared videos of houses and buildings “floating” away during a 2018 earthquake in Indonesia, which violently illustrates the danger.

Dr. Scott Burns, professor emeritus at Portland State University, says the area “has the two characteristics needed” for liquefaction: sandy parent material and a high ground-water table. “It is a big problem!” he wrote in an email.

This isn’t just a problem for Zenith Energy but for the concentration of industry on liquefiable soils along the Willamette River. Portland’s Northwest Industrial District is home to pipelines, electric lines, transfer stations and various other industries.

The Olympic Pipeline connects to the industrial area, ferrying gasoline, diesel and jet fuel from refineries in the Puget Sound. Many of the fuel tanks along the Willamette River were built between 50 and 60 years ago.

In a magnitude 8 or 9 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake, Portland’s Northwest Industrial District could see landslides, soil liquefaction, lateral spreading (where soil permanently moves laterally) and bearing-capacity failures (when the foundation soil cannot support the structure it is intended to support), according to a statement from the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries.

The damage to the industrial zone from a large earthquake could have disastrous effects for Oregon’s economy. Because nearly all of the state’s fuel supply is located in one area, recovery would be severely hampered.

Crucially, Portland’s vast tank farm holds 90% of Oregon’s fuel supply, and it is from this narrow 6-mile stretch of land that most of the state sources its fuel.

In this nightmare scenario, all of the firetrucks, helicopters and ambulances needed in emergency response could lose access to fuel.

According to the Oregon Resilience Plan, a landmark 2013 study on the risks from the next Cascadia earthquake and tsunami: “Disrupting the transportation, storage, and distribution of liquid fuels would rapidly disrupt most, if not all, sectors of the economy critical to emergency response and economic recovery.”

In a statement to Oregon Business, Wattenburger, the spokesman for Zenith Energy, noted that it has multiple contingency plans in place, covering how the company would respond to various disaster scenarios, including a catastrophic earthquake.

These plans, such as the Oil Spill Contingency Plan and the Facility Response Plan, are approved by Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality and the U.S. Coast Guard.

Wattenburger says the plans are not available to the public because they contain sensitive security information. But he says the company regularly inspects its tanks, and the facility also has a large containment area to hold volumes in the event of a breach.

In the wake of a disaster, Zenith Energy would coordinate with the fire department, regulatory agencies and oil-spill response contractors to contain the spill, and clean up and remediate the site.

On Sept. 24, 2019, an oil tanker named American Freedom departed the Chevron dock on the Willamette River in Portland, which Zenith Energy uses to load and ship oil. American Freedom then set sail for a refinery in Long Beach, California, according to data-tracking app MarineTraffic.

Another oil tanker, American Endurance, departed the dock in the early hours of October 23 and sailed to Alaska.

Oil tanker American Freedom docked on the Willamette River Photo: Nick Cunningham

Oil tanker American Freedom docked on the Willamette River Photo: Nick Cunningham

Environmental groups object to Portland becoming a staging ground and conduit for oil at a time when the climate crisis is worsening. Oil produced from Canada’s oil sands ranks as one of the dirtiest forms of production on earth.

Zenith Energy’s terminal in Portland plays a small but vital role in allowing Canada’s oil-sands industry to continue to grow. The goal of Portland’s 2015 resolution banning expansions of fossil-fuel infrastructure was to lay down a marker on a cleaner future.

“That’s why people are so opposed to the Zenith terminal,” Rittenhouse, with Friends of the Columbia Gorge, says. “Because that represents an investment in new oil infrastructure when most people in the environmental community believe that we should be investing our new infrastructure in renewable energy.”

Some business groups argue that outlawing new or expanded fossil-fuel infrastructure makes some of these problems worse. The ban “would essentially freeze the infrastructure in place and block any opportunity for innovative investment like renewable fuels,” Andrew Hoan, president and CEO of the Portland Business Alliance, says.

He added that the zoning ordinance would block upgrades to aging infrastructure, preventing safety improvements, and could also make fuel distribution less efficient if more fuel has to move by truck due to limits on tanks and pipelines.

In July 2019, with little advance notice, hundreds of people packed a community forum where Mayor Wheeler and the city council listened to public testimony. “I’m also concerned, as your mayor, about the possibility of future fossil-fuel exports from the city of Portland. From my perspective, that’s a non-starter,” Wheeler said.

Speaker after speaker demanded an immediate halt to the Zenith expansion, and Mayor Wheeler tried to thread a needle, reassuring an angry public that he was on their side, while also stating that in many respects his hands were tied.

In a statement to Oregon Business, Wheeler says that the focus on Zenith Energy misses the point. “We should be asking broader questions: How do we successfully make a just transition to clean and renewable energy? How do we reshape our economy to be regenerative and one that delivers shared prosperity? If we focus on only one company, we miss the opportunity to ask these broader questions.”

Mayor Wheeler instead shifted to other initiatives that he will push for, such as tightening up safety standards to reduce seismic risk for oil storage tanks, adopting fees on storage of fossil fuels, and finding ways to incentivize electric vehicles and renewable fuels.

Zenith Energy suffered a blow on Oct. 18 when Portland’s Office for Community Technology denied a permit for three additional pipelines that the company wanted to build, which would connect its terminal to the Willamette River.

The pipelines would be used for biodiesel and a substance called MDI, which is used to make products such as polyurethane, adhesives and sealants, according to Zenith Energy.

City regulators said they could not be confident the pipelines would not be used for fossil fuels, which would violate the 2015 city council resolution.

In a statement, Zenith Energy says it was “disappointed” in the permit denial. In a letter to the Office for Community Technology, Zenith Energy also threatened to take legal action if its permit was not approved, arguing that the agency’s denial “lacks any credible basis and conflicts with Zenith’s rights.” The letter says the denial is “utterly at odds” with the city’s goal of boosting renewable fuels.

Environmental groups question the company’s claim that the pipelines are intended for renewable fuels, and they praised the Office for Community Technology’s decision. “We think the denial is correct and reasonable,” says Nicholas Caleb, a staff attorney with the Center for Sustainable Economy.

Barring any unforeseen circumstances, Zenith Energy will continue moving oil to larger markets on the U.S. West Coast. That means that while Portland pursues lofty climate goals, it is simultaneously facilitating the expansion of Canada’s oil-sands industry.

In a statement, Zenith Energy disputed this assertion, claiming that its operations “are completely inconsequential to the decisions made in Canada.”

“The region is really torn between this perception of itself as an environmental leader” while also hosting and supporting polluting industries, says Eric de Place of the Sightline Institute. “Seattle has a big industrial sector, and so does Tacoma, and so does Portland.”

Still, the case of Zenith Energy may offer the “sharpest contrast” in the region, he says, precisely because Portland passed the ordinance banning the expansion of fossil-fuel infrastructure.

By de Place’s count, the Pacific Northwest has blocked more than a dozen large fossil-fuel projects, everything from oil trains to coal-export terminals. He has dubbed the region the “Thin Green Line,” which refers to the Pacific Northwest’s unique position standing between the vast coal, gas and oil reserves in North America on the one hand and hungry Asian markets on the other.

Because there is no coherent national climate strategy, environmental groups and local communities are left to fight the industry on a project-by-project basis, says de Place. “If we had science-based targets for reducing carbon emissions and they were enforceable, I probably wouldn’t fight fossil-fuel projects,” he says.

“All of the ‘keep-it-in-the-ground’ movements are kind of second best. It’s Plan B.”

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.