As airline travel and consumption skyrocket, a move is afoot to slash the greenhouse gas emissions generated by maritime and aviation activity.

The Port of Portland is a recognized leader in green facilities; witness the fleet of natural gas shuttles, LEED platinum headquarters and leadership in the International Airport Carbon Accreditation program, an initiative advocating carbon neutrality for airports.

But there’s a dirty little secret lurking behind this clean green infrastructure.

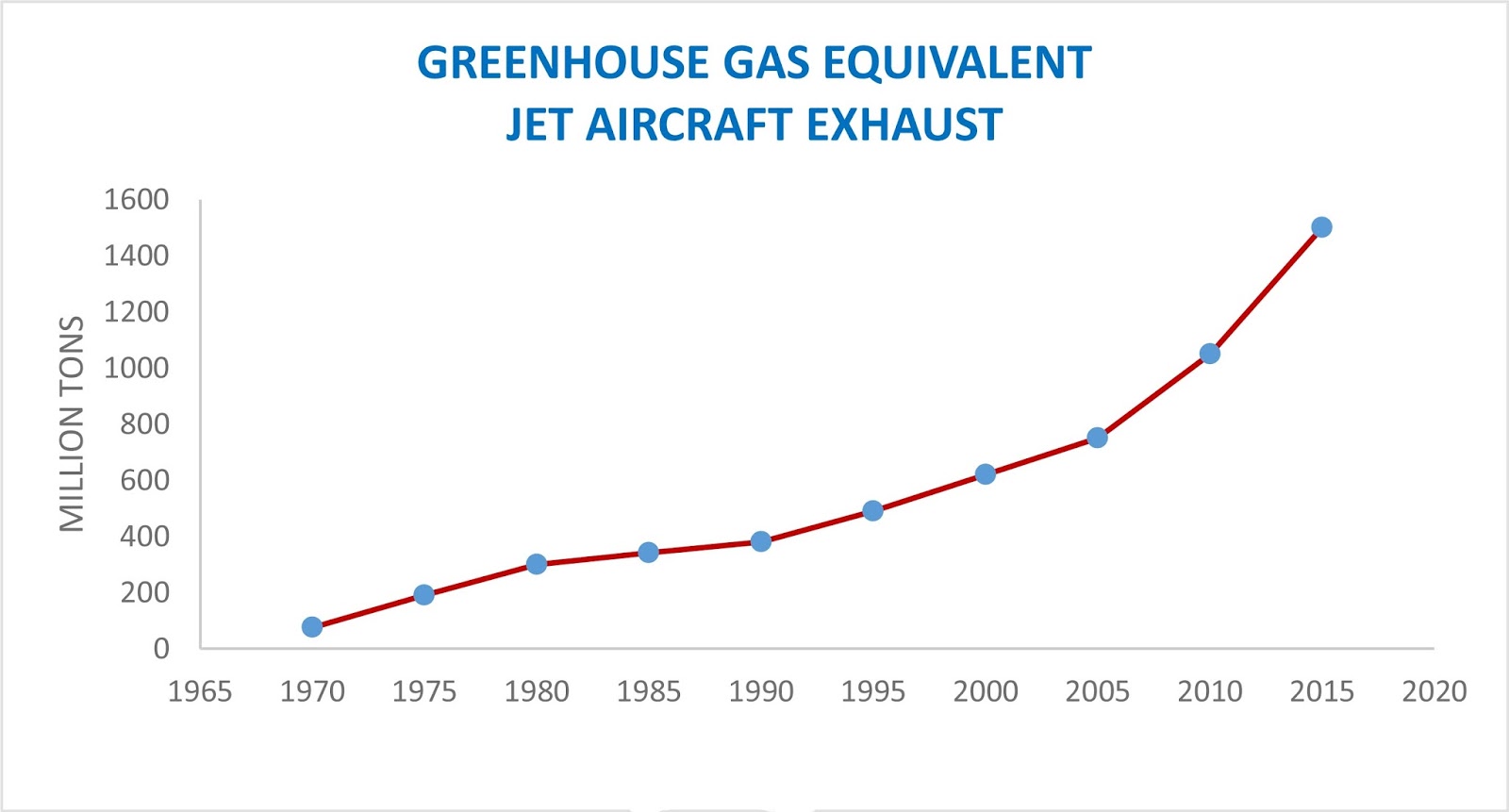

According to new data released by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, greenhouse gas emissions from airline transport in Oregon grew from 1.3 million metric tons in 2005 to 1.7 million metric tons in 2015.

Although emissions from marine transport stayed pretty flat during that period, air and water transportation services* contributed about half the state’s transportation emissions: around 4.4 million metric tons. (Most of the remaining emissions came from trucks.)

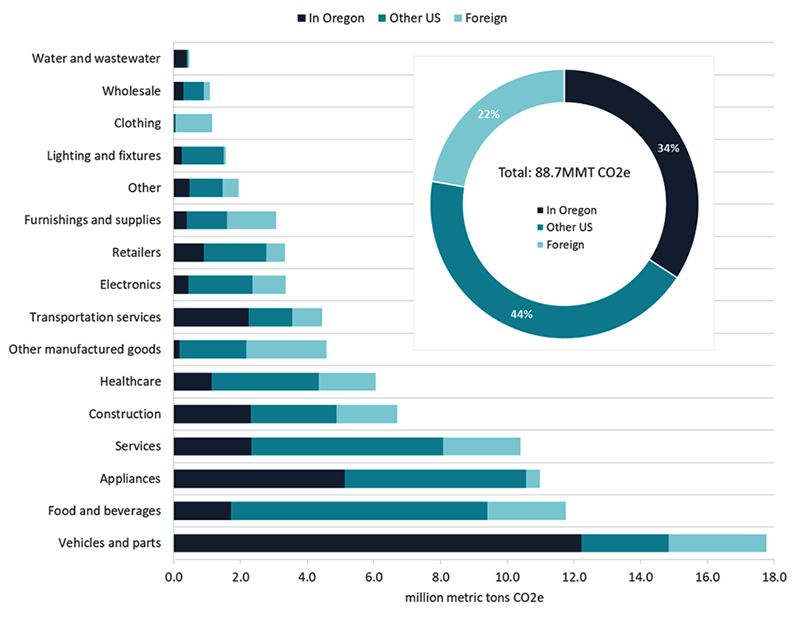

Consumption-based GHG emissions in Oregon reached 89 million metric tons in 2015, according to a DEQ report released today. That’s an increase of 42% since 1990. READ RELATED STORY HERE.

Oregon is not the only place where aviation emissions are flying higher.

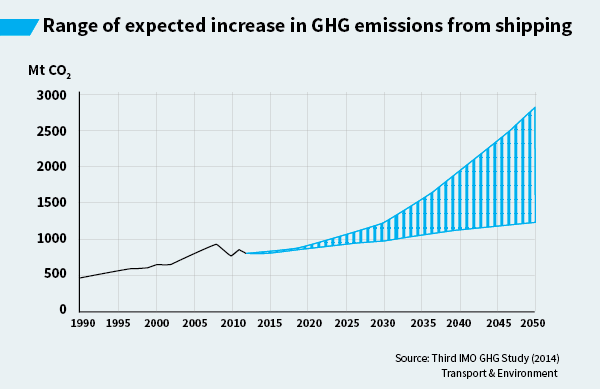

According to a study by the European Parliament environment committee, left unchecked, aviation is on target to increase contributions to global CO2 emissions from today’s 3% to 22% by 2050. Emissions from marine activity show a similar trajectory.

These trends highlight one of the more confounding aspects of emissions reductions policy and practice. Global consumption, along with personal and professional air travel, is increasing — the number of airline passengers at PDX rose 21% over the past decade. Yet airlines and ships are not included in local and international efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Aviation and maritime are not subject to reductions under the Paris Climate agreement, which calls for countries to impose caps on emissions. Portland’s climate action plan, a highly regarded effort to track and reduce emissions county-wide, does not take into account emissions from planes or shipping.

“During a recent legislative session [around a carbon tax], someone asked: ‘are we regulating aviation?’ says Sheldon Zakreski, chief operating officer of the Climate Trust, a Portland nonprofit that promotes offsets to reduce climate impacts. “No one had a clear answer; the reason is it’s not on top of people’s minds. We don’t tend to hear about it, at least as policy.”

There are practical reasons why boats and planes elude climate change planners.

To what city or country do you assign emissions responsibility when a person or product moves from one metropolitan area to another, or one nation to another? That iPhone you bought at the Portland Apple store, for example, traversed multiple cities in China, crossed the Atlantic and travelled through different metro areas in the U.S.

“Air travel emissions, much like emissions from shipping and freight, are a result of activities beyond the scale of any one city,” said Michele Crim, Portland’s climate policy director, in an email. “So they aren’t typically accounted for in city specific emissions inventories.”

Source: Energy Conservation Tech

More than 95% of Port generated greenhouse gas emissions come from activities the port doesn’t control, says Phil Ralston, the Port’s general manager for aviation, environment and safety. “Most of the emissions are from activities that we enable, like airlines, maritime, rather than what we own and operate directly.”

The Port tracks airport emissions and has undertaken numerous initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas pollutants on site, Ralston says. “But there is serious work that we need to do to extend our perspective to what we can’t control.”

Unlike the electricity sector, where utilities can switch from coal to natural gas and, in many cases, solar and wind, there are no commercial alternatives for airplane or boat fuel.

Shipping and airlines are also inextricably connected to economic growth; as a result, aviation and maritime “are the toughest corner of the decarbonization landscape,” says Ross Macfarlane, a board member at Climate Solutions, a Portland nonprofit that promotes clean energy solutions to climate change.

That said, the year 2018 is shaping up to be a game changer.

Airlines and plane manufacturers have been busy working on fuel alternatives since at least 2011, when an alliance including the Port of Portland formed Sustainable Aviation Fuels NW, the nation’s first regional effort to explore sustainable aviation fuels. That effort led to the creation of a Center of Excellence for alternative jet fuels at Washington State University, which investigates aviation fuels, including oilseeds like camelina, forest residues, algae and garbage.

Several alternatives have already been approved by the FAA, and in the U.S., Alaska Airlines and Lufthansa have run several test flights using biofuels. “People were joking; ‘Oh, so you’re going to serve chicken,” laughs Alaska spokeswoman Bobbie Egan, who was on a flight powered by a refined cooking oil blend.

As is the case with the rest of the biofuels industry, “the challenge is scalability,” says Ralston, a former chair of the ACI—North America environment committee. The next step, he says, “is understanding the market barriers and opening up capital markets.”

Oregon is helping chart the course. Red Rock Biofuels is setting up shop in Lakeview, with a plan to convert 136,000 tons of woody biomass into 15.1 million gallons per year of renewable aviation fuels.

The aviation and maritime industries “are the toughest corner of the decarbonization landscape. — Ross Macfarlane.

The venture markets are zeroing in on other options. Zunum Aero, a Seattle-based company backed by Boeing’s HorizonX fund and Jet Blue’s Technology Ventures, aims to bring hybrid electric flight to the skies as soon as 2022.

“As with many things,” Macfarlane says, “progress in sustainable aviation fuels is a combination of taking things we know about to scale and encouraging and hoping for breakthrough technology.”

The maritime industry is about ten years behind aviation in this area, probably because the grittier maritime sector is not as brand conscious as consumer-facing airlines.

“The shipping industry is a very old industry and slow to change and has a long way to go,” says Keith Chapman, director of manufacturing strategy for the shipbuilder Vigor Industrial. Container ships use bunker fuel, crude oil that “came out of the ground and has nothing done to it,” says Chapman. “It’s nasty stuff.”

Nevertheless, innovation is coming to the high seas. Norway, Chapman points out, is already running electric ferries. Engine design standards are also lowering emissions. Slowing ships down could reduce fuel usage, says Macfarlane. The Port, Ralston says, recently exchanged the engine in the Dredge Oregon vessel (responsible for dredging the Columbia River), reducing greenhouse gas output by 25%.

“Air travel emissions, much like emissions from shipping and freight, are a result of activities beyond the scale of any one city.” — Michele Crim, city of Portland

As technological fixes move forward, there are signs that climate policy is beginning to bring planes and boats into the fold.

Starting in 2020, the first ever program to limit aviation emissions will go into effect. The UN designed program, which has been criticized for not being strict enough, does not include an emissions cap; rather, airlines will purchase offsets funding reforestation and other carbon mitigation projects. The new system will be voluntary until 2027, but the U.S. and China are expected to take part when the plan goes into effect in 2020.

And just this spring, a UN shipping agency put together a similar agreement aiming to cut 50% on 2008 maritime emission levels by 2050. (As of April, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia were the only two countries to register objections.)

These policies are a big deal. Yet the question of who’s responsible still haunts efforts to curtail emissions from these two sectors.

“The shipping industry is a very old industry and slow to change and has a long way to go.” — Keith Chapman, Vigor Industrial

There’s a reason why aviation and shipping are the elephants in the room. Oregon’s economy depends on international trade. The state imports about $1.6 billion in goods every year, and consumers’ thirst for products shows few signs of diminishing.

The proliferation of low cost airlines has made airline transport more accessible. And while automobiles are perhaps justifiably vilified for being the biggest emitters, trends in airine travel mean aviation emissions could eventually erase gains made by clean fuel cars.

Status plays a role. People who are otherwise eco-conscious champion airline travel, especially international travel, as a desirable and prestigious form of intellectual and cultural exchange.

In sum: Clean fuel can help green airline travel, but reducing emissions overall, “is something we consumers need to be more cognizant of,” says Macfarlane, “in personal trips and by encouraging solutions at a policy level.”

*Air and water transport services include emissions from household and government purchase of tickets for air and water transport of people, as well as the use of air and water to transport finished goods from the final producer to the Oregon consumer.

A version of this article appears in the June 2018 issue of Oregon Business. To subscribe, click here.