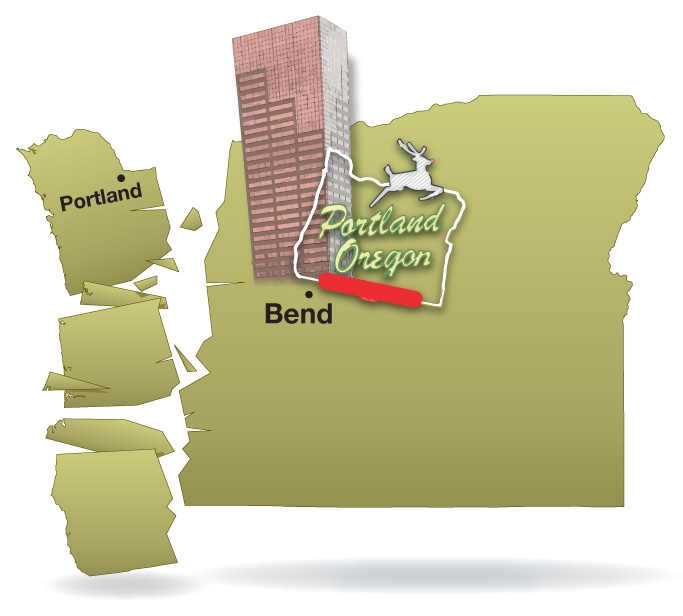

Post-Cascadia, will Bend replace Portland as Oregon’s economic engine?

BEND — If you drive south out of Bend on Northwest 14th Street as if you were going skiing or hiking, you’ll pass a building on the left that stands as a $15 million bet that something horrific is about to happen.

This is a 14,000-square-foot safe house for Cascade Divide, a data center founded by a serial entrepreneur named John Warta, who once ran 16 similar centers in and around Portland. “We are safe from geology here,” he says. “If we have an event, where is the repository of data that allows life to continue? It’s here.”

By now we all know the Pacific Northwest has a 37% chance of suffering a massive earthquake in the next half century, thanks to the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a 600-mile-long fault line off the coast of Newport, where the gnashing of tectonic plates is causing the earth beneath 31 million people to bunch up like a rug caught on a door.

When nature resets itself, as it has done 41 times in the past 10,000 years, the “event” to which Warta refers will leave Portland, Seattle, Vancouver and the entire coast from Mendocino, California, to British Columbia, in the rubble of a “megathrust” quake.

Oregon will never be the same.

And so arises a horrifying yet intriguing question that officials have yet to ponder properly because of the enormous unknowns that lie beyond the certainty that such a quake will happen. Oregon’s economy, political power and population centers have always been anchored on the west side of the state, where the damage would be the greatest.

So what happens to Central Oregon, where the destruction will be relatively minor, if the west is reduced to Mad-Maxian shambles? How does the narrative shift for Bend?

“The spotlight would be on us,” says Eric King, Bend’s city manager. “The whole economy would change, but how? Do we get more goods and services? More manufacturing? This is still a tough place to do business.”

True. But consider how much tougher it might be to do business elsewhere in the state. When the nightmare begins, Ian Madin, chief scientist at the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, believes the ocean floor could lurch 20 feet upward while communities like Seaside, Astoria and Port Orford would sink by as much as 6 feet forever.

Shock waves traveling at 10,100 mph would pin the scales at 9.0, while the aftershocks could hit magnitudes as high as 8.0. Tidal waves would bash the Coast 16 minutes after the shaking starts. As many as 150,000 landslides would kick loose across the state, damming rivers and blocking roads, completely sealing off inland access from the Coast.

Thirteen thousand people: dead. Tens of millions more will have no electricity, water, sewer, police, working roads or health care facilities for years. Rebuilding that which can be rebuilt will cost billions and take decades.

“This would be the biggest type of event the world has ever seen because of the terrain, the environment and the concentration of people,” says Ken Quiner, emergency management coordinator at St. Charles Health System in Bend, who worked on relief efforts after a 7.6 quake struck Kashmir in 2005 and killed 87,000 people. “We’re talking about a level of destruction that sends people back to 18th- century living with horses and wagons.”

Source: Wikipedia — Pakistani soldiers carry tents away from a U.S. Army CH-47 Chinook helicopter after the Kashmir earthquake.

Source: Wikipedia — Pakistani soldiers carry tents away from a U.S. Army CH-47 Chinook helicopter after the Kashmir earthquake.

The shaking would reach Bend about 30 seconds after the quake begins. Dishes might break. Books might fall and windows might crack. But overnight the city of 87,000 would become the staging area for rescue and recovery efforts.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency estimates as many as 13,000 FEMA workers would pour in, while the Red Cross imagines 100,000 refugees flocking to the region. That’s assuming anyone can move at all.

“Where are you going to get gas?” asks George Endicott, Redmond’s mayor and a member of the governor’s task force on quake resilience. “The answer is you’re not.”

With most roads west of the Cascades destroyed or blocked — all but two of Portland’s bridges would be in ruins — U.S. 97 would eventually become the new I-5, Endicott thinks. Commercial air traffic at Roberts Field in Redmond would grind to a halt so C-130s could haul in equipment, medical supplies, fuel and food. Smaller search-and-rescue craft would operate in and out of Bend, Madras and Prineville. The wounded would be sent to hospitals as far east as they could go, to Boise, Denver and Salt Lake, since St. Charles would be utterly overwhelmed.

That much is relatively easy to predict, but the picture really begins to shift in the years following the disaster. “Right now the huge topic is how to prepare for the immediate aftermath, but what happens decades down the road? No one really knows,” says Gary Judd, manager of Bend’s municipal airport, the state’s third busiest for takeoffs and landings.

“It could be one of those weird shifts you see where a disaster changes the whole direction you go as a society.”

Bill Boos, Bend’s deputy fire chief, is skeptical that people would pour into Central Oregon immediately given the damage to infrastructure that would make transportation impossible. At first, survivors tend to stick close to what’s left of their personal fiefdoms. But as time goes by, a sort of PTSD sets in and people look to resettle someplace safe, he says. Managing growth unlike anything the city — any city — has ever seen before would be a major issue, of course.

“Think of Katrina and how a good percentage of the people never came back to New Orleans,” says King, the city manager. He says the city would accelerate its plans to become more dense with more multifamily housing instead of single homes that account for about three-quarters of Bend’s housing stock today. Sewers would expand. Bend’s airport might disappear.

Judd says such rapid growth typically spells doom for small airports like his, as new neighborhoods sprout up nearby and residents quarrel for quiet skies. Redmond airport would pick up the slack. Boos imagines Bend becoming more like Spokane.

“We are safe from geology here.”

— John Warta, founder, Cascade Divide Data Centers

To be sure, Bend’s economy would take a beating in the process. Today the Bend-Redmond MSA GDP alone (excluding Crook and Jefferson counties) is $7 billion per year, says Roger Lee, executive director of Economic Development for Central Oregon, and a “significant” portion of that relies on Portland being intact.

Bend-based Hydro Flask alone sends 95% of its US-bound products through Tacoma where they get trucked to a warehouse in Northeast Portland. (The remaining 5% gets flown directly to PDX.) All of that would evaporate, forcing distribution through overwhelmed ports in California, causing massive delays and likely setting the company back six months.

“When Portland lost container service, that had a huge impact on us, and that’s just a walk in the park compared to what a quake would do,” says Lee.

Even so, the region’s other “highways” could still boost Bend’s economic role in the state following a major disaster, Lee believes. A natural-gas pipeline runs by the landfill east of town and would survive relatively unscathed. It’s also capable of handling a large increase in demand. Hundreds of millions of dollars in investments in telecommunications networks and a robust power-transmission grid mean Bend could attract more tech.

Right now many transpacific communication cables filter into a hub in Hillsboro. With that hub likely destroyed, those cables may end up on the other side of the Cascades, bringing jobs with them, he says.

“When it comes to tech companies, disaster recovery is absolutely at the top of their minds,” says Justin Yuen, founder of Portland’s FMYI. “I could see a scenario where the Portland rebuild takes a lot of time because bridges have fallen and office buildings are no longer available and so companies relocate to Bend.”

Whether any of this comes to pass is crystal-ball stuff at this point, of course, and huge obstacles remain. Redmond airport has one runway that could handle cargo planes, but the taxiways can’t. Bend’s infrastructure wheezes when 20,000 tourists stay in town on a typical summer day. U.S. 97 has but two lanes for most of its length. There are no Nikes, no Under Armours, no Columbia Sportswears: “no ecosystem for commercializing products in your backyard,” Yuen adds.

And yet there is arguably no better city in the state poised to handle such massive change. After all, population projections without a quake say Deschutes County in 50 years will be home to more than 357,000 people, with 195,000 of them in greater Bend, a 127% leap over today’s population.

In the meantime, Warta is out wooing clients with his “diverse power, seismic stability” data center. Upstairs you’ll find emergency office space specifically intended to house workers in the event of a disaster. He has internet connections with four providers. Generators outside can power servers for up to 10 days. Even so, Warta knows his business isn’t completely quake-proof, even in Bend.

“After those 10 days we’ll be like everyone else,” he says. “Screwed.”

A version of this article appears in the October issue of Oregon Business.