Rural areas outperform their urban counterparts.

Update 12/10/2018: This article has been updated with details about a new partnership emerging between Opportunity Insights and the Oregon Business Council.

The American dream is fading—but it’s doing ok in Eastern Oregon.

That was one takeaway from a presentation that Harvard economist Raj Chetty delivered to Oregon policymakers and business executives at Monday’s Oregon Leadership Summit.

The talk contained some striking insights for Oregon, as state leaders desperately seek solutions to ailing schools and a skills gap in tech, healthcare and manufacturing. Chetty’s Harvard think tank Opportunity Insights is launching a first-of-its-kind partnership with the Oregon Business Plan, the state’s principal framework for economic development, to develop a data-driven approach to improving social mobility across the state.

Duncan Wyse, president of the Oregon Business Council, says the partnership is in its early stages and the details are still being worked out. The project will eventually bring researchers from Opportunity Insights to rural communities in Oregon to understand the factors that lead to their high mobility scores. They might also make data-driven reccomendations for affordable housing policy. The think tank will fund its researchers’ travel expenses and technical expertise, and Oregon Business Council and its partners will likely provide some financial support.

“We’re the first state they have come to work with and consider a partnership,” Wyse says.

An “opportunity atlas” that Chetty and his team developed is essentially a heat map of the American dream — the notion that everyone has the opportunity for prosperity and success, as well as upward social mobility for family and children. An interactive map quantifies the American dream by tracing incomes for people in their mid-30s to where they grew up. Using anonymous data from income tax records, Chetty charted economic mobility down to individual neighborhoods. He defined low income as families in the 25th percentile or below of the income distribution.

The result is not a static yardstick for wealthy and poor neighborhoods. It’s a measure of movement from one class to another.

The American dream has been losing altitude since 1940. Almost 90% of American children born during World War II made more than their parents did, but nowadays it’s a different story. Only half of the kids born in the 1980s achieved the same dream.

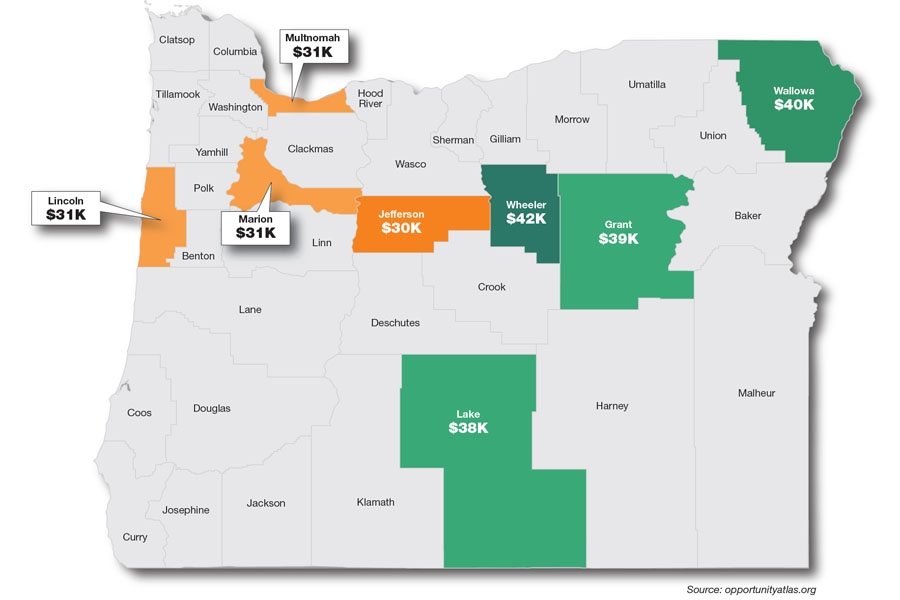

At $31k, tied with Marion and Lincoln counties, Multnomah County is one of the worst in the state for economic mobility measured by household income. Jefferson County comes close behind at $30k. Compared to other urban areas in the nation, however, the Portland metro measures favorably.

Across the country, poor kids growing up in rural areas have a better chance at upward mobility than low-income children in cities, and this insight is reflected in the Oregon data. Grant, Lake and Wallowa counties boast some of the highest rates of economic mobility in the state, and the country.

“There are a lot of very tightly knit communities out there very focused on taking care of all their kids,” Wyse says. “A lot of these communities have been facing tough times, and they’re still able to provide that support.”

Children who grew up in low-income families in these counties make $38-40k by their mid-30s. Baker and Union counties are not far behind, with averages of around $35k. Top of the pack is Wheeler County. Children who grow up in low-income families there go on to make an average of $42,000 in their mid-30s. With only 1,441 residents, however, it’s also Oregon’s least populous county, which could make it an outlier in the data.

Economist Raj Chetty addresses the audience at the Oregon Leadership Summit.

So what are the ingredients in the recipe for economic mobility? They’re not what you might think.

While jobs are a factor, Chetty said, there’s only a weak correlation between job growth and economic mobility. Record numbers of jobs have been recently added to the economy, but low-income people are often not the ones chosen for those positions.

It’s also not enough to build affordable housing. It has to be built in the right places. Much of the nation’s affordable housing stock, Chetty said, is confined to neighborhoods with few opportunities for breaking out of poverty.

High-mobility neighborhoods feature low poverty rates, stable families and what Chetty calls “social capital” – how much you can depend on neighbors in a time of need. Close-knit social ties are one of the reasons rural areas outperform cities when it comes to mobility.

One of the greatest catalysts for mobility is quality education. In a state with the abysmal distinction of 3rd worst high school graduation rate nationally as of 2017, Lake and Wallowa counties boast some of the best numbers. Around 86% of students graduate each year. These areas also have relatively high college graduation rates (27% and 28%, respectively). By comparison, only 76% of Lincoln County students annually graduate from high school.

The state’s public universities, Chetty said, are failing to serve low-income families at the rates that neighboring institutions in Washington and California do. The median household income of parents of University of Oregon students is $126,400. That’s the 11th highest out of 377 selective public colleges.

There are two ways to improve options for children born into neighborhoods with low opportunity. The first is to move affordable housing and low-income families to a better neighborhood. Spurred by Chetty’s research, the Seattle and King County Housing Authorities partnered on the “creating moves to opportunity” program. Low-income families with children under age 15 receive housing choice vouchers that allow them to move to a neighborhood with better opportunity. Chetty said Portland should consider a similar type of program.

The second approach is to improve low-opportunity neighborhoods through place-based investments. That means strengthening social services and schools.

Behind the complexity of the data is a simple revocation of the American myth that anyone who works hard can do better than their parents did. As Chetty puts it: “Where you grew up really matters.”

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.