Arts majors are vanishing, but the role of arts education is becoming more vital to business than ever before.

It felt like walking into the birthday party of an artsy 6-year-old. The room was stocked full of fuzzy cotton balls, colorful pipe cleaner and a projection on the wall of Will Ferrell in his holly-green “Elf” costume.

Not the kind of environment you’d expect from a team of high school and college-age students trying to stop the spread of type 2 diabetes in their community.

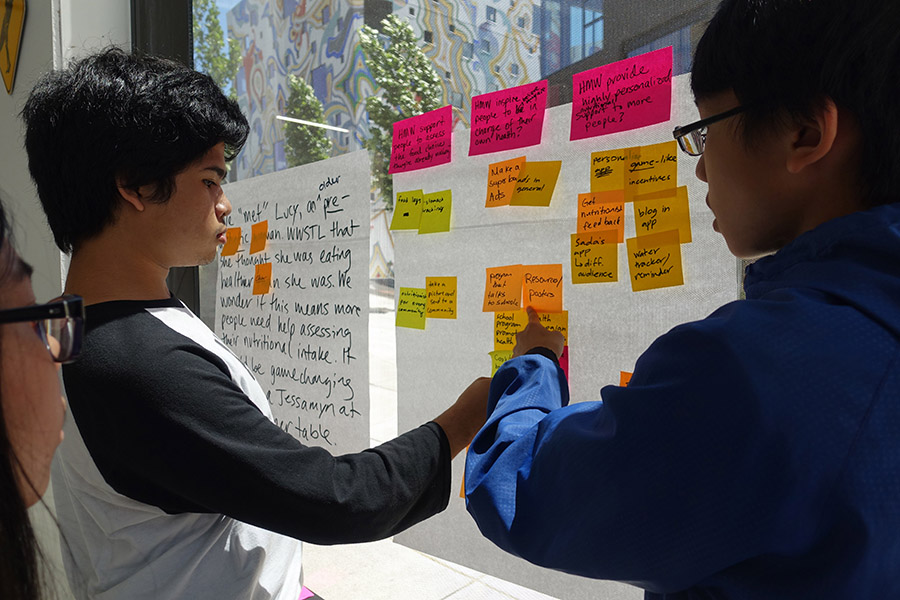

But that’s precisely what the students were up to at the Construct Foundation, an education nonprofit in Northeast Portland. Pink and purple sticky notes covered the walls with contributing factors, names of businesses and outreach ideas scribbled on them.

Students create a post-it plan at the Construct Foundation. Credit Hannah Park

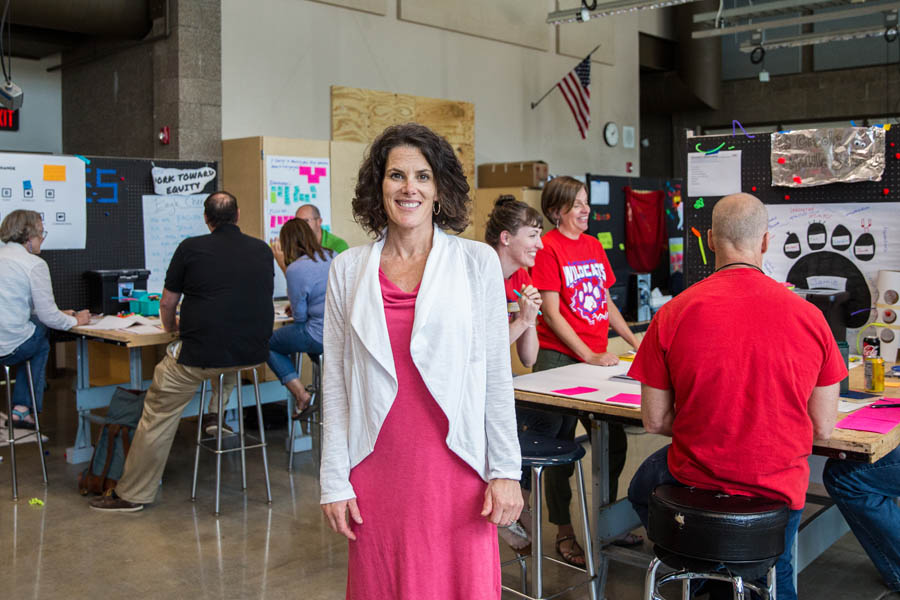

For seven years now, the organization has served as an incubator of new models for learning, with the goal of discovering the teaching methods best suited to foster innovation and problem solving in students. Here, artistic expression and collaborative thinking go hand in hand. According to the Construct Foundation’s president and founder, Gina Condon, the arts are a vital component to teach “design thinking,” a problem-solving mindset that prepares students to approach problems creatively.

“Businesses are demanding these kinds of programs,” says Condon. “Students need to learn how to be creative problem solvers. The creativity and the things students learn as part of these art projects can translate into problem-solving exercises that industry is looking for.”

Yet one could be forgiven for thinking the role of the arts in education is disappearing. The Oregon College of Art and Craft officially shut its doors in May, toppling an age-old pillar of arts education in the state.

Furthermore, in June the University of Oregon laid off the executive director of the Oregon Bach Festival, after budget cuts left the 50-year-old music and dance festival with a $250,000 deficit.

And despite receiving a $5 million grant from the Robert D. and Marcia H. Randall Charitable Trust, Concordia University recently shuttered its humanities degrees, all the while strengthening its core science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) curriculum.

Of course, it’s hard to blame universities. As levels of student debt climb to insurmountable heights, a lucrative job prospect straight out of college has become a necessity, rather than just one of many paths to success. That means more students enter school seeking STEM, leaving the arts to face cutbacks.

Gina Condon at the Construct Foundation. Credit Jason Kaplan

Which is unfortunate, since science and innovation depend on a lot more than the ability to teach university-level STEM. Rachel Jagoda Brunette, program officer at the Lemelson Foundation, says our ability to teach design thinking through arts education is crucial to developing the future generations of inventors and entrepreneurs.

“Design thinking is really at the center of the educational approach we support,” says Brunette, whose organization has awarded more than $175 million to science and business ventures.

The rising popularity of design thinking may cause some arts advocates to heave a sigh of relief, but it does not change the fact that arts subjects are disappearing in higher education. Brunette does not view these changes as proof of the arts decline. Rather, she sees the recent closings as evidence of an evolving, more multidisciplinary approach to higher education.

Students sit in rapt attention at the Construct Foundation. Credit: Hannah Park

“I’ve had a lot of conversation about the death of single-discipline approaches to education,” she says. Narrow curriculums and majors could be a thing of the past, she predicts. “Maybe not even having single-discipline classes, per se, but have the actual courses themselves be multidisciplinary. The arts and liberal arts are a part of that.”

Perhaps the days of majoring in classical French literature are behind us, but so too could be the days of majoring in anything. When viewed from that angle, the closure of Oregon College of Art and Craft is more about the changing nature of the university and its ability to provide a well-rounded curriculum than it is a coup against the arts.

RELATED STORY: Innovation Without Borders

As for Concordia University, executive vice president of business development and innovation Shawn Daley agrees. The closure of the university’s liberal arts majors doesn’t translate into a closure of its arts programs, only a step toward a more multidisciplinary academic model, he says. “The nature of what a college degree means is evolving. We’re folding the arts and humanities into our broader curriculum.”

While organizations like the Lemelson and the Construct foundations demonstrate the importance of arts learning to the fields of science and business, the skills associated with exposure to the arts go beyond problem solving. In an economy still rocked by automation and artificial intelligence, “soft skills,” such as the ability to empathize with a consumer, have the potential to become even more prized.

“What we’re seeing overall is that the skills we’re lacking are the personal skills. The medical field, for example, has become highly computerized,” says Thomas Potiowsky, director of the Northwest Economic Research Center at Portland State University. “What we’re lacking is good old doctor’s bedside manner.”

While we still don’t know how to teach bedside manner, when it comes to empathy, the arts could be key. A study this year from Rice’s Kinder Institute for Global Research found students who received arts education have social advantages and increased levels of empathy over students with similar economic backgrounds who did not.

Congresswoman Suzanne Bonamici, who represents Oregon’s 1st Congressional District, believes our ability to teach the arts is vital to our global competitiveness. The congresswoman has been a consistent champion of changing STEM into STEAM (the “A” stands for the arts) at the national level.

“Nobel laureates in the sciences have been much more likely to have had arts training,” she explains. “As we move toward the jobs of the future, technical skills aren’t going to be as important as critical thinking. They have good test scores in China, but they’re not having a party about it because they aren’t creating things,” she says, quoting former University of Oregon professor Yong Zhao.

Congresswoman Bonamici at a registered apprenticeships hearing

Having a narrow focus on STEM has the potential to hamstring a student’s ability to thrive in the real world, says Bonamici. “When I [served on] the Education Committee and the Science Committee [at the federal level], I kept hearing again and again, ‘We need more students in the STEM fields, we need more diversity in the STEM fields.’ Then I got out to the real world, and what I would hear from employers was that we need people who can communicate and collaborate.”

That is to say, students who feel railroaded into the STEM fields to stay competitive in the job market could be in for a rude awakening. As more graduates with STEM majors flood the job market, young job seekers may realize too late they need soft skills to stay competitive.

Bonamici has worked to ensure as few students face this conundrum as possible. Since serving on the House Committee on Education and Labor, Bonamici founded the STEAM Caucus, a bipartisan group of lawmakers who advocate for the arts in K-12 education. The caucus has already had success, including the passage of the STEM to STEAM Act of 2019, which allowed arts programming access to a wider range of federal grants.

Despite the Trump administration’s calls to eliminate federal cultural agencies, Congress voted to increase art funding in the 2018 budget. And there’s reason to believe Oregon is already ahead of the curve. The state Legislature passed the Student Success Act earlier this year, which restored critical funding to music and arts programs.

The city of Portland also has safeguards in place to ensure all students have arts exposure. “Thankfully, in Portland we have the arts tax,” says Marna Stalcup, director of arts education at the Regional Arts and Culture Council. The tax, though controversial, ensures students get access to arts education of some kind, regardless of income levels.

The value of the arts in education will continue to be recognized, but given the rising cost of a university education, arts departments will probably continue to face cutbacks.

Perhaps the arts will survive in diminished form, meant as minors and stepping stones to business and technology courses. Perhaps the opposite will be true; automation and artificial intelligence could consume so many disciplines that the arts become indispensable.

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.