|

Former PGE chief executive Peggy Fowler retired in 2008 and now serves on the boards of three public companies, including Hawaii Electric Industries.// Photo by Matthew D’Annunzio |

In the mid-1990s, former Oregon Gov. Barbara Roberts reached out to Nike and a few banks and insurance companies with the intention of landing a seat on a corporate board of directors. But the offers never came, says Roberts, whose resume included presiding over an economic expansion as governor, a background in small business, and a five-year teaching stint at Harvard. Around the country, male governors received an “automatic board solicitation when they finished their terms,” recalls Roberts. But at the time, she says, the same opportunities were not available to women. “We did not receive that outreach,” she says, “or the opportunity for additional income after leaving office.”

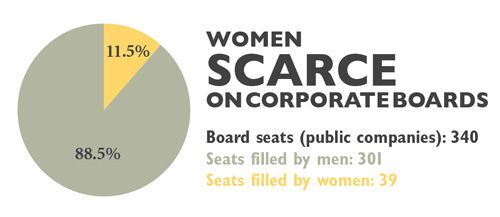

Fifteen years later, Roberts says the situation is changing for female governors. But the underlying problem of a male boardroom monoculture persists. In a survey of Oregon’s 46 publicly traded companies, Oregon Business found that women occupy only 39 of 340 existing board seats and that almost half of the 46 companies have no women on their boards at all. And since several female directors are “duplicates” — that is, they serve on more than one board — the total number of women serving on Oregon’s public corporate boards is actually 35. Oregon Business did not gather data on privately held companies in Oregon because many private companies either do not have boards or will not reveal the names of board directors.

The dearth of women involved in corporate governance is a social equity issue — publicly traded companies compensate directors an average of $76,000 a year — and a business performance issue. An emerging body of global research suggests boards with female board members outperform those without female members across industry sectors. A 2007 analysis by Catalyst, a New York-based nonprofit dedicated to improving opportunities for women in business, found that Fortune 500 companies with higher numbers of female board members outperform those with fewer women based on several financial benchmarks. Measured by return on sales and return on equity, for example, companies with the highest percentages of women board directors experience better financial results than those with the least number of women. “The numbers are startling,” says Mary Boughton, senior regional director for Catalyst.

|

“I’d love to see more women pursue technical degrees,” says Kirby Dyess, who serves on three corporate boards.// Photo by Matthew D’Annunzio |

Exactly how and why the presence of women on boards improves a company’s financial performance is difficult to pin down. The consensus seems to be that women bring a different perspective to the table, in part because of their status as outsiders, and that “the more types of thinking, the better decisions the board will make,” says Peggy Fowler, retired CEO of Portland General Electric and a director serving on the boards of PGE and Umpqua Holding Corp.

Companies also need more diverse boards for image purposes and to better understand the needs of an increasingly complex and diverse workforce and marketplace. “If you’re sitting on a board where the customer base or buyers are female, you’d have a very difficult time understanding your market with an all-male board,” says Kirby Dyess, principal of Austin Capital Management, a former Intel vice president and a member of PGE’s board of directors. She cited the utilities industry as an example of such a “diversified” sector.

Companies with a critical mass of female board members also tend to hire more female corporate officers than companies without women on the board. According to another Catalyst report, companies with at least 30% women board directors in 2001 had on average 45% more women corporate officers by 2006, compared to companies with no women board members. In both the financial performance and corporate officer reports, the key number of female directors appears to be three. “That’s the magic number where change actually happens,” says Boughton. Oregon’s women executives agree. “When you have more than two women on a board, there’s an additive effect; you have more confidence to speak out,” says Patricia Moss, chief executive and chair of the Bank of Cascades and one of three women who sit on the board of MDU Resources Group, a Fortune 500 company based in North Dakota.

Only four of the 46 public companies in Oregon have at least three women serving on their boards of directors: Nike, StanCorp, Albina Bank and Schnitzer Steel. There are only two companies with female chief executive officers — Schnitzer and Bank of the Cascades. Both have at least one woman on their boards.

|

Judith Johansen, president of Marylhurst University, serves on the boards of four companies, including the Idaho Power Company and Roseburg Forest Products.// Photo by Matthew D’Annunzio |

Gender disparity in the boardroom is an issue that extends far beyond the Oregon border. Nationwide, only 15% of board members in Fortune 500 companies are women. In the European Union, 9.7% of board members in the top 300 companies are women. Women make up about 12.5% of directors at the 100 largest publicly traded companies in the U.K., and many companies have never had a woman on the board.

Concerns about board diversity are also unfolding at a time when the responsibilities of directors are becoming more demanding. Corporate cataclysms ranging from the collapse of Enron to the 2008 financial crisis have increased pressure on boards to hold CEOs accountable to shareholders, business experts say.

“Regulation has gone through the roof,” says Dyess, referring to the hundreds of pages of quarterly and annual reports she is responsible for. “Particularly in today’s world, you’re putting yourself on the line.”

The pressures of the job are making it more difficult to find male or female candidates willing to serve. But heightened board scrutiny is just one of many reasons why so few women serve on corporate boards, Dyess and other female board members say. “The problem is there is not a pipeline of women who are coming up and making it into the C-suite: CEOs or CFOs,” says Judith Johansen, president of Marylhurst University and a director on Schnitzer Steel’s and Bank of Cascades’ boards. Johansen, a former president and CEO of PacificCorp, adds that boards prefer CEOs as directors because they know what it’s like to be in the CEO’s chair.

“Having senior experience with your own boards raises the bar in terms of board performance,” she says.

|

Peggy Fowler credits former OPB journalist Gwyneth Gamble Booth, communications executive Carolyn Chambers and former PGE chief executive Kay Stepp for being the first women to serve on Oregon boards.// Photo by Matthew D’Annunzio |

Moving onto a board “is frequently about developing relationships with people that are built through experiences being in touch with other executives serving on boards,” says Kay Stepp, a former COO of PGE and one of the first women in Oregon to be invited to serve on a corporate board in the 1990s — a time she describes as a kind of Dark Ages, even if the 21st century doesn’t seem much brighter.

Stepp cites her own experience as an object lesson in how to secure a board seat. After leaving PGE in 1989, she worked with Planar’s founding chief executive as an executive coach, and then was invited to sit on the board. As CEO of PGE, Stepp participated in an American Leadership Forum class with Ron Timpe, CEO of StanCorp. In 1998, she was invited to be a director on that company’s board.

A growing number of women have access to such networking opportunities as they move through the management ranks, says Stepp.

“But it’s an evolutionary process,” she says. In male-dominated sectors such as high tech or manufacturing, many women face another hurdle: insufficient technical or science proficiencies.

“We’re not graduating a lot of female engineers,” Dyess says “If you don’t have any background in the field, the question is what expertise are you going to bring to the board.” As of October, approximately eight women serve as chief executive or chief financial officers on Oregon’s 46 public companies.

The challenges facing women interested in securing a board seat raise the question: How do the men who are making the decisions about corporate strategy, oversight and director positions in Oregon view the issue? Several board leaders, including Patrick Jones, chair of Lattice Semiconductor, and Kurt Widmer, chair of Craft Brewers Alliance, declined to be interviewed for this article. Mentor Graphics, which has an all-male board, also turned down requests for interviews. Other men were more forthcoming, echoing the arguments of female board members regarding the challenges and benefits of putting more women on boards.

“We’re always on the outlook for candidates who will diversify the board,” says Don Graber, chair of Precision Castparts’ eight-member, all-male board of directors. “But we also look for people who have a manufacturing-type background and females are tough to find.”

Columbia Sportswear, one of the seven public companies with two women on its board, “has made great strides in revitalizing its brand,” says Steve Babson, chair of the board’s nominating committee. “That’s attributable to key people in the company, many of whom are women.”

To be sure, many Oregon companies are concentrated in the wood products, manufacturing and other traditionally male-dominated industries. But the list of Oregon public companies without any women on their boards — a list that includes FLIR, Electro Scientific Industries, Premier West Bank, and LaCrosse Footwear — transcends any individual sector. There is no research about gender and financial performance in Oregon. However, a growing number of studies in Europe show that companies with more female board members outperform those with fewer women, regardless of the type of industry. That research includes a 2007 Finnish study and an analysis of European listed companies conducted by the consulting firm McKinsey & Company, both of which found a correlation between the percentage of female board members and improved corporate financial performance.

Decades after the women’s movement and countless women-in-business diversity initiatives, many business leaders agree on the economic and social justice value of increasing women in the boardroom. What still isn’t clear is how to make it happen.

In Europe, policy makers have decided the only solution is regulation. In 2003, Norway was the first country to establish a 40% quota of women on boards, followed by Spain in 2007 and Iceland, which implemented quotas last year. In January, France passed a law requiring that by 2017, women must represent 40% of board members on the largest publicly traded companies. The U.K. is also considering quotas.

In the U.S., business leaders seem to favor a market-based approach. “I think quotas are crazy,” says Johansen, reiterating the importance of getting more women into executive positions. Instead of mandating percentages, agrees Fowler, companies should provide board diversity training and publicly disclose the number of women in management and the boardroom. “That can move us to where we want to be,” she says.

In September, the National Association of Corporate Directors hosted a meeting in New York titled “Move the Needle: Diversity and Women in the Boardroom as a Strategic Business Imperative” that was organized around just those themes. Featuring 100 top corporate leaders, the meeting focused on increased networking and education for women interested in board positions, corporate diversity disclosures and greater board turnover.

Increasing female board participation may also require boards to consider candidates outside traditional industry sectors, says John Becker-Blease, an Oregon State University business professor. “I would argue for an inclusive view of board composition, to bring fresh revolutionary ideas to companies,” he says. Some corporations are leading the way. Between 1998-2008, the CEO of Texas Instruments crafted and implemented a plan to make female directors 40% of the board.

Since women now comprise 60% of the MBA student population, change may occur more organically at the other end of the corporate ladder, says Lee Koehn, a corporate recruiter in Lake Oswego. Growing attention to a board’s fiduciary responsibilities is also “leading the market away from a good ol’ boys network” and toward candidates with established competencies and experience, Koehn says.

But whether demographics, corporate initiatives and heightened scrutiny of company operations will be enough to counter prevailing forces remains to be seen. And until change does occur, Oregon’s business leaders must contend with the fact that only 11.5% of Oregon’s publicly traded corporate board positions are held by women.

Maybe there’s an upside, says former governor Roberts, noting the situation can be good fodder for public speaking. “When I would give talks to women’s organizations about our successes and failures,” she says, “I would make a joke: ‘I don’t even want to talk about corporate boards.’ You can always use that for a laugh.”

Linda Baker is the managing editor of Oregon Business. Contact her at [email protected].

| Public companies WITHOUT women on boards | Public companies WITH women on boards |

|

|