From businesses such as Nutcase Helmets to Bike Friday, Oregon’s bike madness fuels a $150 million industry. Not to mention that there’s an organized bike ride every 27 minutes.

GEARED UP

GEARED UP

From businesses such as Nutcase Helmets to Bike Friday, Oregon’s bike madness fuels a $150 million industry. Not to mention that there’s an organized bike ride every 27 minutes.

BY BEN JACKLET

Last summer, when gas prices were hovering around $4.50 a gallon, the owners of Clever Cycles in Southeast Portland had a business problem. Their new bike shop was proving so popular that they couldn’t keep up with demand. They had to shut down their business at the peak of the season to restock the family-friendly utilitarian bicycles selling like crazy in bike-crazy Portland.

A few miles away, Sacha White of Vanilla Bicycles is faced with a similar challenge. Anyone hoping to order one of his hand-built bikes will have to wait at least five years to get it.

It’s a familiar scenario for Jonathan Maus, the Portland-based entrepreneurial blogger who covers the local culture, sport, business and politics of bicycling for his red-hot website, bikeportland.org. Maus has had to hire journalists to keep pace with all the news as the bicycle culture evolves and the industry grows larger and more complex, in a metro region where an organized bike ride takes place every 27 minutes on average, where the wild mud-worshipping sport of cyclo-cross has gone big-time, where bicycle documentaries sell out on opening night, and where the legion of bike commuters includes Portland Mayor Sam Adams, Congressman Earl Blumenauer and key members of the Metro Council and the Oregonian editorial board.

The market for anything connected to bicycles in Portland runs rich and deep, and entrepreneurs are sprinting to create new ways to tap into it. About 50 new bike-related businesses have sprung up over the past two years here, and while some are destined to remain forever fringe if they survive the downturn at all, others have tremendous potential.

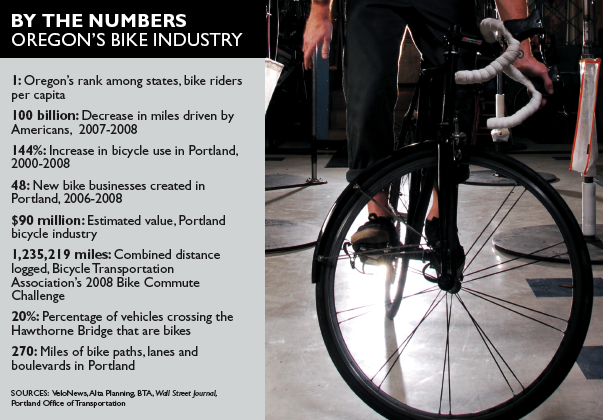

Add up the revenues for retailers such as the Bike Gallery, manufacturers such as Chris King Precision Components, organized rides such as Cycle Oregon and professional services firms such as Alta Planning and Design, and you get about $90 million in annual sales, in Portland alone. That figure would likely grow to well over $150 million statewide if you factor in bike sales in Ashland, Sisters and Hood River; repairs and rentals in mountain-bike-mad Bend and Oakridge; the cyclical wanderings of students and faculty in Corvallis; the creations of Eugene-based Bike Friday, Burley Design and Co-Motion Cycles; and the far-ranging economic impact of Cycle Oregon.

|

The jobs generated by all of this activity are unlikely to offset the thousands that have been lost in Oregon’s motor vehicle industry as dealerships close and RV manufacturers hit the skids, but they do generate excitement for yet another Oregon niche industry with a dreamy upside, in the tradition of solar power, craft brewing and organic farming. Market share is tiny but growing explosively. As big as biking has gotten here, for all of Portland’s accolades as the nation’s best city for cycling, only 8% of downtown workers commute by bicycle. That number can and no doubt will grow much larger, sooner rather than later. It isn’t difficult to imagine an immediate future where homegrown bike businesses outnumber tech start-ups.

But let’s not get carried away. For all of the diversity and creativity of Oregon’s bicycle industry, it remains relatively small, surprisingly immature and deeply fragmented. Even if statewide sales total $150 million, that is less than a quarter of the annual revenues of the Wisconsin-based Trek Bicycle Corporation, which employs 1,200 people. Despite the well-publicized proliferation of Oregon frame builders trained at the United Bike Institute in Ashland and showcased with a special exhibit at the Portland International Airport, the vast majority of the bicycles sold in Oregon are built elsewhere. So are the helmets, rain gear and accessories marketed by Oregon startups such as Nutcase Helmets, Showers Pass and Bike Buddies. The bike builders who benefited the most from the crazy run on the Clever Cycles shop in July were all European companies. “If we could have found a viable option locally, we would have gone for it,” says Martina Fahrner, a co-owner of Clever Cycles. “But no one could deliver bikes in the volume that we sell them.”

Still, while the manufacturing base for the nation’s bicycle industry may not be in Oregon, the brain trust increasingly is, and so are the riders. Five years ago it would have been unusual to see an adult in work clothes commuting to their job with a child pedaling along in tandem. Today that sight is as commonplace as the latest horde of cyclists taking over the Hawthorne Bridge and the East Bank Esplanade during the morning commute.

Even the wet, dark months of Oregon have not kept the wheels from spinning because the cyclo-cross phenomenon has encouraged demand for a whole new type of $3,000 bike that gets beat up during each race and requires expensive repairs and upgrades. The bike craze accelerated as gas prices rose, but it does not appear to have abated as prices have plummeted. Bike-crazy newcomers continue to pour into the city, boasting car-free lifestyles with “zero mpg” bumper stickers on their rides. They spend the $5,000 or so that they might have spent on cars each year on coffee, food, beer, and anything that has to do with bicycles.

|

Jonathan Maus moved to Portland from Santa Barbara to become a part of the bike culture. Now he is at the center of

it and to a certain extent, its spokesman. He started with a blog on oregonlive.com, and then set out on his own to build bikeportland.org, one of Oregon’s most successful blogs.

“I could see the value of connecting all these things going on in the community and putting them together in one place,” he says between sips of coffee at a cafe with a bike-through window. “I was blown away by the response, and by how much was going on, this outpouring of creativity that is constantly evolving.”

The more rides, gatherings, policy plans, police incidents and startup businesses Maus covered, the more came to his attention. His blog started drawing huge reader response, dozens of comments for each new post, a constantly updated conversation that extended well beyond rides and events and into the future of transportation, energy use and the American city. Advertisers from inside and outside of the industry, including Oregon icons such as Powell’s Books and New Seasons Market, recognized the value of his site, and advertising revenue enabled him to run his blog as a business and even buck the trend by hiring journalists.

“It is certainly the best blog in Portland,” says writer Jonathan Nicholas, a former columnist for the Oregonian and founder of Cycle Oregon. “It’s a textbook case of how to build a blog.”

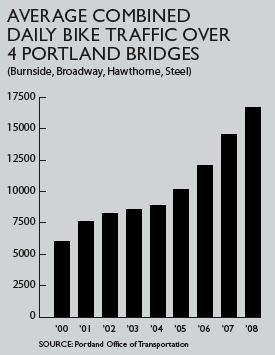

It’s also a window into a business world with enormous potential. At last count Maus’s site contained links to 26 local frame-building companies, 42 bicycle shops and 40 Portland bike-related businesses such as the Rose Pedals Pedicab Company and SoupCycle, a company that delivers soup by bicycle. Many of these businesses have made their debuts since Maus first began blogging regularly in the spring of 2005. Over that same period, 2005-2008, bicycle traffic crossing Portland’s four bike-friendly bridges has shot up from 10,192 trips per day to 16,711, a 64% increase.

Maus thinks the growth and evolution of the bike culture will continue even as the larger economy slows, due to a steady influx of new talent moving into the scene, new bike builders and designers opening shop or joining established teams to feed the demand.

“It’s all growing like crazy, and a lot of it is within three miles of where we’re sitting,” he says. “We’ve got 8% of downtown workers commuting by bike. If this keeps up we will see 25% and more businesses will keep opening. We’re going to see equipment makers, roadside service stands. It’s going to happen. This is not some weird phase. It will be sustained. Even in the winter.”

|

About a half mile away from Maus’s bike-through cafe, Mia Birk has converted a historic building in Portland’s Central Eastside into a bicycle-planning factory. Birk, who holds a degree in international economics from Johns Hopkins University, served as Portland’s first bicycle coordinator. In collaboration with then-City Commissioner Earl Blumenauer, she completed the city’s first bicycle master plan in 1996 after a tour of 18 European cities. At the height of the city’s program she oversaw a staff of five and a budget of $1.5 million, building a network of bike lanes, trails and boulevards that has grown to nearly 270 miles, setting the stage for the bike explosion of the past decade.

Now she is doing similar work for Portland-based Alta Planning and Design, the nation’s largest bicycle planning firm. Alta compiles bicycle and pedestrian plans for small Oregon communities such as Manzanita and bustling global cities such as Dubai.

Birk’s view is that the most cost-effective investment a community can make toward a sustainable future is to build smart bicycling infrastructure. She also encourages businesses to encourage bike commuting for physical and mental health — and to save money on health-care premiums. “The bicycle is a simple solution to a whole host of complex problems,” she argues, from obesity to global warming to stress.

Birk says Portland’s bicycle industry has been long underrated economically. Alta’s most recent report, released in September, found that the value of the industry grew by 38% from 2006 to 2008 and expanded from 95 to 143 businesses, including 12 new small-scale bike builders. Another number in the report seemed too large to be true, so Birk and her team re-counted and crosschecked before publishing: Portland holds nearly 4,000 annual rides, races, events and tours. That’s an average of one ride every 27 minutes.

Birk compares the bike industry to the craft brewing industry in that it is part cultural and part economic, with ideals playing a significant role. “In Oregon people start up businesses based on what they love to do,” she says, “and then they figure out a way to make money off it.”

Some companies, such as Clever Cycles and Vanilla Bicycles, have figured out the business end quite quickly. Others have flailed, partly because they lack the knowledge necessary to run a business. Jennifer Nolfi, creative services industry manager for the Portland Development Commission, has worked closely with local frame builders to encourage the industry to organize, grow and build jobs. “Getting them to agree on anything can be a challenge,” she says. “The other challenge is helping them to learn the business side of things.”

PDC has sponsored cyclo-cross races, a “bike manifesto” in the Pearl District, a handmade bike exhibit at the Portland International Airport and the North American Handmade Bicycle Show. But when the city organized classes to teach frame builders the basics of bookkeeping, attendance was so sparse that the program was canceled.

|

About 120 of the 500 or 600 students who go through the United Bike Institute (UBI) of Ashland each year study the art of frame building. As the only school in the world with a program dedicated to custom bike building, the school cranks out a lively mix of graduates eager to get their creations on the road.

One example is 32-year-old Natalie Ramsland, who worked on and off as a Portland bike messenger for about 10 years before enrolling in a frame-building class at UBI. Bringing her new skills back to Portland, she rented an inexpensive workspace and established Sweet Pea Bicycles. She and her husband, Austin, took the cash gifts from their wedding and bought welding tanks and torches. He handled the marketing end of the business, the blog and the website, while she honed her craft. She started by designing bikes for friends and family, improving with practice and benefiting from Portland mentors who taught her the fine points of custom fitting and fabrication.

Ramsland honed in on the largely untapped market for custom bikes for women, studying a rider’s biomechanics and range of motion and then designing a bike to fit the individual. Orders grew steadily, and then took off after Bicycling Magazine profiled her as an accomplished woman bike builder breaking into a field long dominated by males. Now her backlog of orders is up to a year and a half. She is building custom bikes for customers from Boston and California and thinking about expanding into a larger workspace.

Her goal is not to crank out as many bikes as possible, but to make the best. “We want the Oregon bike to be like the Maine lobster or the California avocado. We want to make Portland the place to go if you want to buy a custom bike.”

To a certain extent, that is already happening. So many independent frame builders are migrating from the Ashland bike school to the Portland bike scene that UBI president Ron Sutphin is considering setting up a satellite campus in Portland. He has been working with the PDC to find a good Portland location and was close to pulling the trigger at press time.

To a certain extent, that is already happening. So many independent frame builders are migrating from the Ashland bike school to the Portland bike scene that UBI president Ron Sutphin is considering setting up a satellite campus in Portland. He has been working with the PDC to find a good Portland location and was close to pulling the trigger at press time.

Such a move would strengthen the connection between the UBI and the Portland bike scene. Sutphin also has high hopes about improving cohesion and savviness within the industry as a whole.

“Bicycles have been around for at least 100 years, but it is one of the most immature industries out there,” he says. “There are no industry standards, no trade groups. We are just way behind when it comes to taking ourselves seriously enough to get to the next level. One of the reasons is it has been run by enthusiasts who have had a hard time learning to be profitable and consistent enough to actually employ people.”

Jerry Norquist agrees. Norquist is the ride organizer for Cycle Oregon who has made that annual ride legendary for its logistical efficiency. He started his career working for Trek in Wisconsin and worked his way up to manager of bicycle brands before moving on to Specialized Bicycle Components in California and then Cycle Oregon.

Norquist has been trying to build enthusiasm for his plan to redevelop the Memorial Coliseum into the Portland Bike Box, with headquarters for bicycle groups and businesses, frequent track and BMX races and shared tools and resources for frame builders. Norquist would like to see the industry get to the next level. He acknowledges that attracting a top-tier manufacturer such as Trek or Cannondale to Oregon would be a long shot. “They employ thousands of people where they are, and they have social obligations,” he says. “At the same time, the next Trek is out there, and we have a good opportunity to attract the next big thing, with all that’s going on in Portland and in Oregon.”

Portland already has attracted Chris King Precision Components, a company legendary for its well-designed, expensive parts. Ever since the company moved from California to Northwest Portland rumors have circulated about its plans. The company has grown to 75 employees and is hiring frame-building experts, but has not announced specific plans regarding its bike-building future in Oregon.

Other medium-sized companies are also prospering. The Bike Gallery has expanded to six locations throughout Metro Portland. In Eugene, the folding-bike experts at Bike Friday and the tandem cycle specialists at Co-Motion are both well positioned, and while Burley Design LLC has downsized in recent years, it saw demand for bike trailers rise when gas prices spiked last summer.

While Cycle Oregon operates as a nonprofit rather than a business, its economic reach is substantial, with $150,000 in annual payments to the small towns that host the rides, plus $100,000 in annual grants to build new sports facilities and gathering places. “Then there’s all the money spent by 2,000 people tearing through Oregon on bikes every year,” adds Nicholas. Economic development and fun were the twin motivators behind Cycle Oregon when Nicholas wrote the newspaper column that spurred it 21 years ago. “We started with the idea that 50 people might show up,” Nicholas recalls. Instead the ride drew more than 1,000 people and has been a hit ever since.

A similar show of enthusiasm has propelled cyclo-cross from the fringe to the main stage.

Brad Ross, who founded Cross Crusade 16 years ago, says it began as a side sport to fill the gap between the summer bike racing season and the winter skiing season. The sport evolved quickly into its own thing, with specialized bikes and riders, and Portland has been the epicenter from the beginning. Participation is growing by 20% each year, says Ross. The 2008 season featured eight races and 10,000 participants, followed by the season finale at Portland International Raceway. Racers range from heavily sponsored elite specialists to C-category riders looking to spin around in the mud and then drink beer with their friends. “Our attitude is all about inclusion and fun,” says Ross. “I think that contributes to the bike culture as a whole. The vibe from cyclo-cross has definitely rubbed off.”

The sport’s surge also has created a significant new source of income for bike shops. “Cyclo-cross gives shops an excuse to stay open for three months and make money when they would have been sitting on their thumbs in the winter,” Ross says.

It remains to be seen how well the discretionary spending that fuels cyclo-cross will hold up during a serious economic downturn. Another broader question involves how prepared bike startups are for the coming storm. Oregon’s bicycle industry is so diversified that it may hold a stronger position than other sectors. But to call bicycles recession-proof would be a stretch.

“It’s a scary deal for everyone,” says Michael Morrow, a former creative director at Nike who founded Nutcase Helmets in 2005. Nutcase has sold 20,000 bike helmets in Denmark alone over the past 15 months, at 68 euro a pop. Morrow hopes to sell 100,000 more next year globally, but he’s keeping his forecast conservative due to the financial crisis, hoping that bike helmets aren’t something people will stop buying.

Other bike businesses are hoping the same holds true for their products, whether they are the stylish bike bags of Portland-based Queen Bee Creations, the functional bike racks of Eugene-based CETMA or the custom frames of Grants Pass-based Keith Anderson Cycles. It remains to be seen how many niches the bike industry can support, but for now the opportunities outweigh the risks, especially in comparison to the economy as a whole. And while the ongoing collapse of the nation’s auto industry is delivering a painful blow to the U.S. economy, it’s not hurting the outlook for Oregon’s bicycle industrial complex.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]