BY LEE VAN DER VOO

A forest collaboration saves the Rough & Ready Lumber Company.

|

| The 1977 crew |

BY LEE VAN DER VOO

Last mill standing. On its face, the resurrection of the Rough & Ready Lumber Company in Cave Junction looks like a single turn of luck in a small town — a win for the last remaining mill.

But what’s happening at the Illinois Valley mill also signals a shift in timber management in Oregon. And it took more than just luck. Interest and funding from the governor’s office is being credited with the resurrection, along with a partnership between mill owners and the money-savvy nonprofit Ecotrust. The secret sauce, however, is the involvement of the Southern Oregon Forest Restoration Collaborative, which helped reshape the face of timber harvesting and overcome a key obstacle to mill production: environmental opposition to timber sales. It’s a recipe state leaders aim to keep mixing.

“We’re hopeful. It’s a different day,” says Tom Tuchmann, the forest conservation and finance advisor for Gov. John Kitzhaber. He describes how a focus on forest restoration and thinning, especially where decades of fire suppression have spurred overgrowth, has set the table for mill rescues of this kind. With input from traditional tough-on-timber opponents, the collaborative crafted a timber-sourcing plan that enabled the mill to maintain capacity by retooling to process smaller logs more efficiently.

Strange bedfellows. The Illinois Valley isn’t the place you might expect such agreement. Famous for its timber wars, it was once home to 35 mills. The community of 10,000 is also dotted with artists and musicians, environmentalists and off-grid dwellers. When the spotted owl was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1990, advocacy lawsuits halted federal timber sales and shuttered many mills, redefining the economy. Roughly 80% of timber in this area is federally owned. Private timber sales brought some supply, but production costs soared as logs were sourced farther away.

|

| New planer mill |

The Rough & Ready mill cut back one shift in 1990 as a result of those pressures, thinning workers from 225 to 175. Another shift was cut later to combat rising costs as supply remained scarce. After several years of deferring capital improvements and losing a key source of private logs, the mill’s third-generation owners, Jennifer Phillippi and her husband, Link, ruefully told their remaining 88 employees the mill would close last April.

“The day we had to meet with them, and tell them and look at their faces was just devastating,” Phillippi says. “I knew that they had counted on us.”

A collaborative solution. The mill offered severance pay and began working with state and federal officers on employment benefits, and with a local office that hosted classes and meetings for workers. That effort cued the attention of state and congressional leaders, who began calling the Phillippis as they hunted for a mill buyer and talked to auctioneers about worst-case scenarios. Sen. Ron Wyden, Rep. Greg Walden, Rep. Peter DeFazio and the governor’s office all offered help, and have since made efforts to restart federal timber sales.

The governer’s office contracted with the Southern Oregon Forest Restoration Collaborative to find 10 million board feet in thinned timber annually, and within two hours of the mill. That available supply would help leverage financing to update the mill to an

efficient small-diameter production — one that could stay in business. The collaborative found 28,000 board feet close to home by demonstrating how thinning in some areas could actually improve recovery odds for spotted owl and eliminate fire fuel close to homes, all while preserving ancient forests.

|

| Trailer tipper dumping biomass for cogeneration plant |

“We have a letter from Fish and Wildlife saying, ‘Hey, we like the strategy. It works for us,’” says George McKinley, executive director of the collaborative. He described how the endangered species listing for the spotted owl and concern about salmon habitat have made it otherwise difficult for federal agencies to say yes to timber sales.

Their blessing is important — 80% of the timber in the Illinois Valley is owned by the federal government through either the Bureau of Land Management or the U.S. Forest Service. Those forests produce 1 billion board feet of timber a year. Yet less than 1% is harvested annually because of habitat concerns and efforts to avoid controversial timber sales. Thus, half of that timber is dying instead.

“That’s a pretty striking number,” says Phillippi. “And what we’re seeing are these massive wildfires that are taking care of that growth naturally.”

|

| Jennifer Phillippi (center) planting millionth tree with her husband, their daughter, a nephew, and Jennifer’s mother and brother |

Forest health. Wildfires are chiefly what convinced a lot of former timber opponents that some forest management is necessary. Now, McKinley says, more people understand that leaving a forest alone doesn’t necessarily keep it healthy. Since forming in 2005 to examine such problems, the collaborative has aimed its philosophy for forest management at reducing fuel for fires and improving habitat, management tools that are now being embraced rather than eschewed by environmental advocates. In nine years, the collaborative has grown to include 15 agency partners, including environmental groups, as well as federal, state and local governments.

Their timber-sourcing plan for Rough & Ready helped spur a $1 million state loan from the governor’s strategic reserve fund and another $4 million in federal and state funding via the New Markets Tax Credit. The funding is being used to make long-deterred capital investments in the mill, making it more efficient and adding automated features that better its bottom line. Portland-based Ecotrust, one of only a handful of community-development entities headquartered in Oregon authorized to invest the tax credits, managed the transaction.

Rough & Ready will reopen in mid-June, running one shift per day and rehiring 67 of its workers. The news is good for former yard foreman Dan Harwood, who spent a year wondering what lay ahead. “At first it was a real depressing thing … I’ve done sawmill for 28 years. That was all I’d ever done. I was third-generation sawmill, so I really enjoyed working there.” The lost tax revenue from the mill and other recession-hit businesses helped fuel a decline in sheriff services, an uptick in crime and a slump in people’s spirits in and around Cave Junction. Now, he says, “having the mill reopen has brought people back around a little bit.”

Tuchmann notes 23 forest collaborations have been born in Eastern and Southern Oregon over two decades, and more are moving west.

|

|

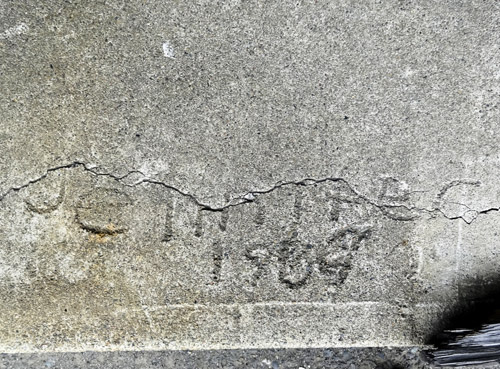

| Concrete pour and inscription: 1969 and 2014 |

“We see more organizing, and those who do organize are getting to ‘yes’ at a relatively swifter pace,” Tuchmann says. Such efforts have already paved the way for other, similar successes. And Tuchmann says the state plans to encourage more teamwork on timber-sourcing plans for struggling mills, while habitat restoration and thinning remain a focus. Meanwhile, Ecotrust is pursuing similar opportunities in economically depressed regions of the West. It has already revitalized two other mills with a focus on thinned timber: the Ochoco Lumber Company and Roseburg Resources Company.

“I think the fact that lumber manufacturers and Ecotrust can work together on a project like this is a pretty nice story,” says Phillippi. “We’ve all evolved to where we’ve developed that trust.”