As the economy falters and more people lose their health benefits, hospitals brace for the impact of the uninsured.

As the economy falters and more people lose their health benefits, hospitals brace for the impact of the uninsured.

BY JASON SHUFFLER

DIAGNOSIS: BROKEN

As the economy falters and more people lose their health benefits, hospitals brace for the impact of the uninsured.

BY JASON SHUFFLER

|

There are times when someone needing medical care at the Oregon Health & Science University’s emergency room refuses help. It’s not because they don’t want it, it’s because they can’t afford it.

“Patients worry because they can’t pay,” says Dr. Javad Mashkuri of OHSU’s emergency department. In many cases these reluctant patients are part of the growing number of people in the state without health insurance, he says.

Hospitals throughout the state, like their uninsured patients, also are worrying. The economy is in the tank and as unemployment rises, people losing their jobs also lose their employer-based health benefi ts, which has hospitals expecting a fl ood of newly uninsured patients needing medical care.

Already 621,000, or 1 out of 6, Oregonians don’t have health insurance, according to 2007 U.S. Census data. Analysts agree this amount will grow, though it’s unclear by how much. “As unemployment rises, the number of uninsured goes up,” says Sean Kolmer, head of research and data at the state agency Oregon Health Policy and Research. “Everyone expects the number to increase. I would be shocked if it didn’t.”

Nationally, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates a 1% increase in unemployment leads to 1.1 million more uninsured Americans, although this equation can’t be directly applied to Oregon’s rising unemployment rate.

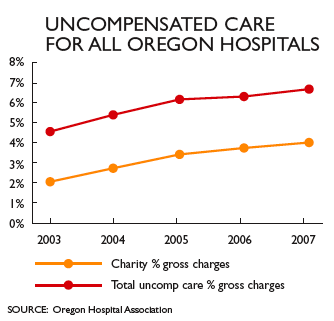

A swell of patients unable, or unwilling, to pay their medical bills is not good for a hospital’s financial footing. Oregon hospitals say it likely will add to the already exploding amount of bad debt and charity care they report each year.

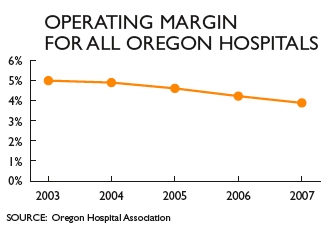

In 1997, hospitals statewide reported a total of $139 million in uncompensated care. By 2007 this amount ballooned 530% to $876 million. The Oregon Hospital Association expects this number to reach a billion dollars by the end of 2008.

“As margins get tighter for hospitals, it’s forcing them to make a whole host of diffi cult decisions,” says Kevin Earls, vice president of policy and advocacy at the association.

Uncompensated care and its role in skyrocketing medical costs are at the center of the greater debate about whether the overall health-care system is fi nancially unsustainable. Oregon’s hospitals say rising uncompensated care forces them to trim costs and rethink spending plans.

“At some point raising the cost of care erodes the quality of care,” says Aaron Crane, chief fi nancial offi cer at Salem Hospital. “We can either cut expenses or charge people more money.”

Economists say unemployment will worsen before it improves.

“A possible, even likely scenario is a very bad recession, similar to that in 1982” when the unemployment rate was 12.1%, says John McConnell, a health-care economist who studies uncompensated care and is a professor at OHSU’s Department of Emergency Medicine. “Many hospitals in the state have expanded over the last few years and thus they may have a higher degree of liabilities that make the challenges even more diffi cult.”

Early warning signs are being seen in hospital spreadsheets and have executives scrambling to make sense of what it might mean for the fi nancial health and goals of their hospitals. “We have an urgency to our fi nancial constraints,” Crane says. “It’s on our plate and we have to fi gure it out.” Salem Hospital is forecasting $62.5 million in uncompensated care for fi scal year 2009, a 13% increase from $55 million in 2008.

Providence Health & Services in Oregon already has seen a 22% increase over last year in its uncompensated care costs and expects a spike in uninsured patients in the next six to 12 months.

Consequently, Terry Smith, chief operating offi cer of the seven Providence hospitals in the state, says Providence is postponing capital spending projects such as building a new medical offi ce and a separate data center. He also says the hospital likely will not spend as much on outside consulting services, but may need to hire more case managers because uninsured patients typically need more fi nancial counseling.

One early indicator at OHSU has CFO Diana Gernhart particularly concerned. The number of fi nancial assistance applications the hospital has approved for uninsured patients who have already received care jumped 40% between July and October of 2008. From 2003-2008, OHSU’s uncompensated care fi gure went from $36 million to $89 million.

In December, OHSU announced an unspecifi ed amount of layoffs and instituted a hiring and salary freeze in part because of the increasing charity care on their books. “Folks are needing more assistance,” Gernhart says. “I think it will go up. I know we’re going to get more uninsured patients.”

At Oregon Safenet and 211, the state’s referral helplines for community and government services, the number of callers seeking health-care-related services and assistance has increased 10% in the past year.

Typically, there’s a lag time before emergency rooms and hospitals see a spike in uninsured patients from an economic downturn because employer-based health benefi ts can last months before they expire.

But history reinforces what hospitals are anticipating. In 2003, the Oregon Health Plan, the state’s Medicaid insurance program for low-income residents, made cuts that disenrolled about 50,000 recipients. Researchers studied statewide data for the 24 months before and after the cuts and found it led to a 50% increase in overall uninsured admissions into hospitals.

As hospitals grapple with rising uncompensated care and brace for more uninsured patients, the cycle of sharing the costs percolates to everyone in the health-care system. Through “cost-shifting,” hospitals offset some uncompensated care by passing the losses on to paying customers.

“The commercially insured are paying for the uninsured,” says Pamela Vukovich, CFO of Legacy Health System. “In essence, uncompensated care is a tax on the insured.” She says that rising uncompensated care threatens the hospital’s ability to reinvest money into aging facilities and buy new equipment for staff.

McConnell estimates up to 9% of a commercial health-care insurance premium is paying for uncompensated care in the state. “The larger concern is how does this impact everyone else,” he says.

That concern is where the debate begins among stakeholders in the state’s $19 billion health-care system: hospitals, insurers, employers, consumers and government. Yet hospitals know that passing on the expenses of uncompensated care to paying customers only leads to more uninsured and uncompensated care.

As hospitals shift their losses, health-care insurers pass on the costs to employers and private customers. In 2008 alone, employee premiums at a company with 50 or fewer employees increased by 11%, according to the Oregon Insurance Division. The rate for individual coverage jumped nearly 18%. Premiums are likely to grow higher this year, experts say. “I don’t know if commercial insurance will be able to keep up,” says OHSU’s Gernhart.

The trend is crippling the fi nancial capacity of employers to offer health benefi ts, say some analysts, potentially adding to the number of uninsured in the state. According to the Economic Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based economic think tank, the number of Oregon workers under 65 receiving health benefi ts from their employer has decreased by 5% in the past eight years.

“The number of employers offering health benefi ts certainly isn’t increasing,” says Rod Cruickshank, president of the Portland-based benefi ts consulting fi rm The Partners Group. If the economy doesn’t turn around and company earnings plummet this year, Cruickshank says employers may need to renegotiate less health benefi ts for employees.

“As reform discussions take place, we have to pay for health care in a way that has minimal disruption on people with insurance,” says Earls of the Oregon Hospital Association.

Even as hospitals expect an infl ux of uninsured patients, the social safety net designed to help in tough times is feeling the pinch.

The Oregon Health Plan is the state’s primary program to help the uninsured. In response to the deteriorating health of the economy in the fall, the state Department of Human Services forecast a 15% caseload increase for the OHP Plus programs for the 2009-2011 biennium. The DHS report cited an increase in unemployment and a bad economy as reasons for the spike.

But as the economy sours, so does public financing for such programs. Already state economists have forecast a billion-dollar revenue shortfall for the next biennium. DHS, the parent agency of the Oregon Health Plan, will likely have much less money to help more uninsured.

If health-care stakeholders fail to come up with a solution to fi nance more OHP recipients, more uninsured patients are likely to show up at hospitals without the ability to pay for services.

The path of uncompensated care often begins in hospital emergency rooms. Experts say ER care is much more expensive than preventive care. The federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act of 1986 requires ERs to treat patients regardless of their ability to pay.

Researchers of the Oregon Health Plan study concluded the 2003 cuts led to a 20% spike in uninsured visits to emergency rooms statewide.

At Providence, about 20% of uninsured patient care originates in its ER. Over the last year, the number of uninsured seeking emergency care has increased 4.5%, about onefi fth of all emergency room patients.

At the six Legacy hospitals in the Portland- metro area, 75% of uncompensated care comes from their emergency departments. Legacy reports seeing 1,541 more uninsured patients at its emergency departments in the fi rst seven months of its current fi scal year compared to last year. At OHSU, only 6% of all uninsured patients originated in its ER.

In many ways, a new recession underscores the urgent need for health-care reform. As health-care providers and as not-for-profi t businesses, hospitals know they need to work closely with all the stakeholders to remain solvent. “Hospitals differ because they routinely offer services that consistently lose money,” says Earls, of the Oregon Hospital Association.

But much rests on the ability to fi nd agreement about who should pay more to treat the uninsured. The Oregon Health Fund Board, a seven-member taskforce of health-care stakeholders throughout the state, issued their fi nal reform recommendations to Gov. Ted Kulongoski and the Legislature in November.

In December, the governor issued his budget and proposed expanding the Oregon Health Plan in the 2009-2011 biennium by an additional $696 million. That revenue would be raised by a new 4% provider tax on hospitals. The current tax is 0.63%.

The OHA says funding for the health plan should come from state’s general fund instead because Medicaid payments aren’t covering the entire costs to treat OHP patients.

“The lesson we have learned trying to fund the Oregon Health Plan through a dependence on provider taxes is that it’s not a stable funding base,” says Earls.

“The crux of health care is it can’t continue this way,” says Legacy’s Vukovich “It’s unsustainable.”

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]

The path of uncompensated care often begins in emergency rooms. At OHSU, about 21% of its ER patients in 2007 were uninsured.

The path of uncompensated care often begins in emergency rooms. At OHSU, about 21% of its ER patients in 2007 were uninsured.