How telemedicine became the new normal for health care in the COVID-19 world.

Elizabeth Powers spends a few days each week driving for miles around Wallowa County, situated in the crook of Northeastern Oregon, right along the Oregon-Idaho-Washington borders. The family physician at Winding Waters, a nonprofit health organization, visits residents scattered across bucolic frontier towns, home to an estimated 7,000 residents.

When she cannot see them in person, she talks to them on the phone or over Zoom, the popular video-chat app, sometimes from inside her parked car.

The rural populace of Wallowa County has few options when it comes to health care access; Winding Waters serves 66% of the county each year. While Powers usually sees them in one of Winding Waters’ clinics, she also conducts visits remotely, even more so now because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’ve been really committed to eliminating any barriers patients have to achieving their optimal health,” says Powers, who has been at the organization since 2006. “And one of the big barriers in a rural environment is physical [places] are pretty distant from each other.”

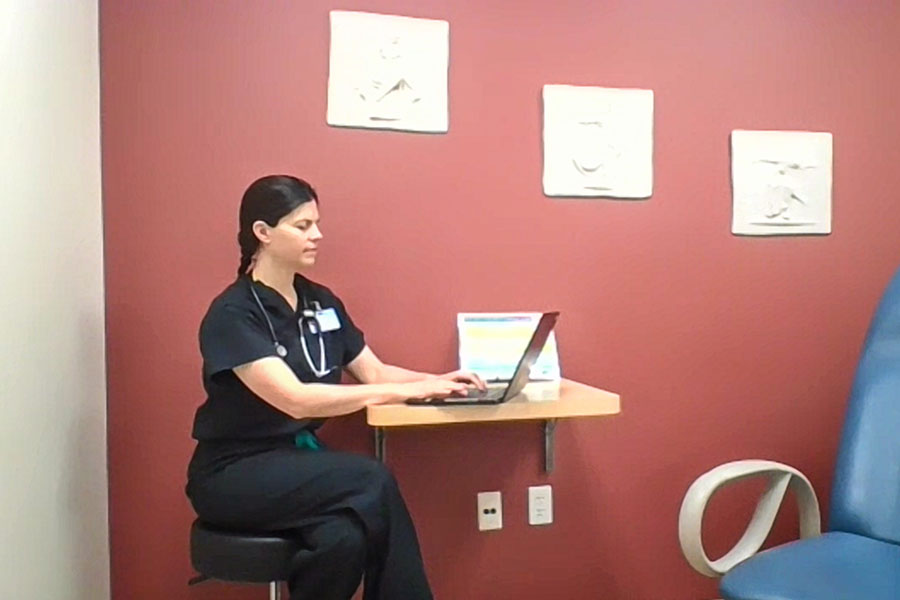

Dr. Elizabeth Powers at Winding Waters Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Dr. Elizabeth Powers at Winding Waters Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

First coined in the 1970s, telemedicine comprises the technology to deliver health care — including consults, exams and prescription refills — remotely without a face-to-face visit. (Many in the health-care industry use the terms “telemedicine” and “telehealth” interchangeably.)

The tools to examine and monitor patients — think video conferencing and digital patient records — have been around for years. It just has not ever been widely used until COVID-19.

The Portland-based data and technology nonprofit OCHIN says half of all medical visits conducted today are remote. Before the pandemic, says CEO Abby Sears, roughly 1% of visits were considered telemedicine, even though many of Oregon’s health care facilities had the capability.

“I don’t think anyone would like to have a pandemic to create this opportunity, but one of the benefits that we’re experiencing is this complete transformation of using telemedicine for providing care,” says Sears.

The global pandemic has upended virtually every aspect of our lives, health care notwithstanding. A trifecta of a highly contagious virus, shelter-in-place orders and relaxed insurance-reimbursement rules has resulted in the transformation of telemedicine from being an option that few dabbled in to health care’s new gold standard.

And while virtual visits will not replace seeing doctors in person, professionals now using this technology hope it will continue to be a mainstay long after the pandemic.

Telemedicine technology became essential to ensure people could still be helped by a medical professional — whether it was COVID-19-related or not — without risking exposure to the virus. Companies stepped up to connect doctors with the community.

In March Portland tech startup Bright.md provided health systems across the U.S. and Canada with a free coronavirus self-evaluation patient tool. CEO and co-founder Ray Costantini likens the technology to a virtual medical resident, which uses artificial technology to screen patients.

Its mobile Smart–Exam platform is able identify around 500 different diagnoses. In May the company raised $16.7 million from a group of investors, indicating how confident the investment community is in telemedicine technology.

OCHIN, which works with more than 15,000 providers in 48 states, says 75% of its membership nationwide successfully transitioned to providing telemedicine services in the wake of the pandemic.

Sears, who has helmed the tech company for 20 years, says it has 34 members in Oregon, from small organizations like Winding Waters to large offices such as the Multnomah County Health Department.

Winding Waters first used telemedicine in 2016 to reach its most rural, and often elderly, patients. But even then, it was not widely used by the organization’s eight doctors or their patients.

In frontier doctor fashion, it is why Elizabeth Powers still makes house calls, although she and a nurse care manager have also assisted patients with basic IT setup to help enable telemedicine capabilities.

“Before COVID we were doing about a dozen telehealth visits a week. In the last four weeks, we’ve averaged about 160 a week,” says CEO Nic Powers. (He is also married to Elizabeth Powers.)

Elizabeth Powers uses telemedicine to see her patients for their annual wellness exams, consult about back or knee pain, and prescribe a steroid cream after seeing a red rash through the computer screen. “It is really helpful when we are there to walk patients through shared decision-making,” she says.

David Handler says his remote visits with Powers went smoothly. In May the 75-year-old retired Enterprise resident underwent a colonoscopy, which he says was postponed two months because of the pandemic.

Instead of visiting Winding Waters for his pre- and post-surgery visits, he simply logged into Zoom on his computer. “The only thing that didn’t happen was I wasn’t weighed,” he says with a laugh. “It was as good as if she was sitting in the room with me.”

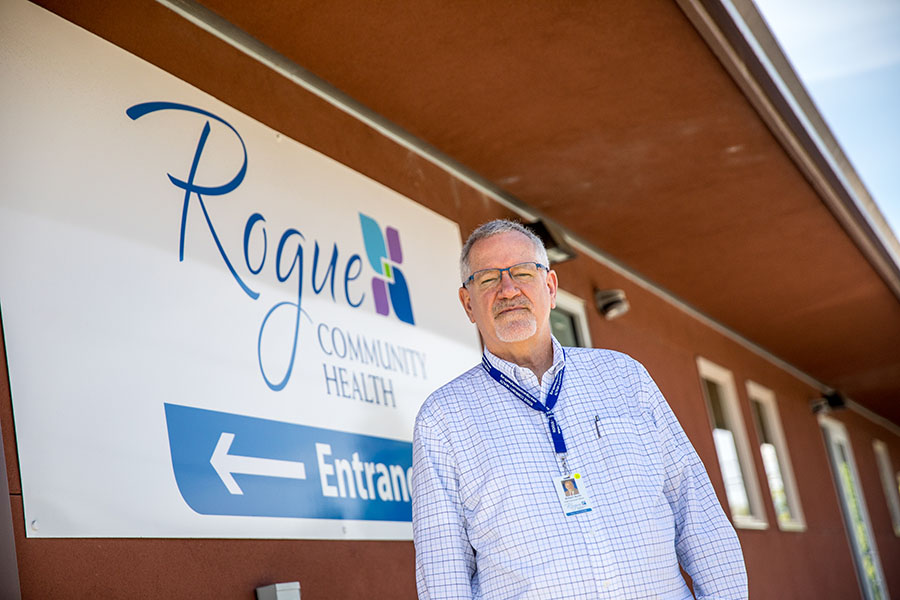

Behavioral-care providers are also finding telemedicine beneficial. William North, the CEO of Rogue Community Health in Southern Oregon, says remote behavioral-health appointments have increased during the pandemic.

There has also been a decrease in appointment cancellations and no-shows. “I think it gives someone a sense of control,” he says. “They’re in their own home, they are more comfortable than sitting in a clinic or sitting in a place that they’re not comfortable or used to going to.”

William North, the CEO of Rogue Community Health Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

William North, the CEO of Rogue Community Health Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare, which has four locations in Portland, was able to convert between 80% and 90% of its appointments to telemedicine, including behavioral health, substance-use treatment, crisis intervention and even support groups.

The organization serves approximately 18,000 people each year in the tricounty area, many of whom are insured through the Oregon Health Plan. “COVID-19 was a big factor in our development of a broad telehealth program across the entirety of our organization,” says Jeffrey Eisen, the chief medical officer and a psychiatrist.

“We knew that we needed to consider telehealth in a much more robust way for our clients and for our workforce.”

Providers are also finding that care management, which often does not require face-to-face interaction, offers a good, long-term use of the technology. “I think one of the areas that it’s been a little surprising is that it’s been useful for advance-care planning,” says Powers.

These past few months, she has been able to connect her patients with specialists and have co-visits, many of whom otherwise would not be able to have these appointments.

According to OCHIN, there are only 30 specialists per 100,000 residents in a rural area versus 263 specialists per 100,000 people in an urban area. “Before [COVID-19,] that was something they would never have considered,” Powers says of specialists connecting via telemedicine. “I actually think we’re providing better medical care than ever before because we’re able to use telehealth.”

While the challenges of this year have given the health care industry opportunities to establish telemedicine’s potential, it has also exposed its limits. This includes specialized tests or emergency health situations. Powers recalls a patient who initially consulted with her virtually but required an ultrasound. “She had to come in to see me,” she says, “because we had exceeded telehealth capacity.”

The pandemic pressed the health care industry to innovate quickly, but it also forced the federal government and insurers to increase reimbursement for remote-care services.

The move was a shot to the arm for many of Oregon’s medical clinics, which depend on revenue from in-person visits, especially during the roughly four weeks that elective surgeries were prohibited across the state. According to a recent Harvard University study, primary care visits have dropped by almost 50% during the COVID-19 health crisis.

Currently, the reimbursement rate for Medicaid patients is the same whether they are seen in person or over Zoom. For federally qualified health centers like Rogue Community Health and Winding Waters, the telemedicine reimbursement rate for its patients on Medicare is $92.03. But providers there can bill $173.50 to see those same patients in person.

Even with increased telemedicine reimbursements and higher use, North says that Rogue Community has been operating at a loss since April, and he expects the organization to continue to do so for the duration of 2020. A handful of staff who were unable to work from home during the shelter-in-place order were also furloughed.

In Wallowa County, Nic Powers says Winding Waters has also experienced a financial downturn, although none of its 68 staff have been furloughed or laid off. He says the decrease of in-person visits equates to a roughly $30,000 loss each week, which began in late March.

On average the clinic now sees 350 people per week, down from 500 before the pandemic. “The way the model works right now, we get paid the best if a patient comes into the clinic and is seen,” says Powers. “Financially, I don’t have a good answer. Telehealth is only a good thing financially for us if [the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] and the [Oregon Health Authority] continue to pay us and figure out how to pay us at a fair rate.”

It is a discussion that has been circulating in Congress and in state legislatures, even before the coronavirus hit the U.S., but has yet to be resolved. In this year’s short session, the Oregon Legislative Assembly introduced a bill requiring the Oregon Health Authority to ensure telemedicine is reimbursed at the same rate as an in-person office visit. The bill received stakeholder and legislator support and passed the House before the session abruptly ended.

As the state emerges from its months-long shelter-in-place, the question hangs over the health care industry: How long will the virus-induced telemedicine reimbursement rates remain?

Brad Hilliard, the spokesperson for the Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services, says the guidance on telemedicine reimbursement rates — first issued in March — will remain in effect through at least December 31. The federal government has released similar statements.

“I think it’s important that the payment system continues to incentivize the use of telemedicine and doesn’t disincentivize this approach,” says Sears. “It only will continue if [providers] can get reimbursed at a level of parity with an office visit.”

Many doctors and clinics are still committed to offering telemedicine services and remain hopeful reimbursement rates can be locked in. “The parity in telehealth payment has enabled us to utilize this fully and help people,” says Eisen at Cascadia Behavioral Health.

“It allows some additional flexibility and work-life balance opportunities for providers of care, and it also perhaps is an attractive feature for recruiting and retention of a solid workforce.”

Dr. Jeffrey Eisen, left, of Cascadia Behavioral Health, with associate Matthew Hatch Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

Dr. Jeffrey Eisen, left, of Cascadia Behavioral Health, with associate Matthew Hatch Photo by Jason E. Kaplan

While telemedicine has transformed health care this year, it is only beneficial and therefore successful if its users likewise have access. Patients need high-speed internet to reliably video-chat, and a device to download and use telemedicine apps.

In rural and marginalized communities, these are often barriers. “It’s one thing for me to learn how to use Zoom; it’s a whole other thing, though, if I’m having this conversation with you and every fifth word is cutting out,” says Sears.

Take the small towns of Enterprise and Joseph in Northeastern Oregon. Its residents get internet via a fiber-optic cable from La Grande, about 70 miles away. Nic Powers says the cable has accidentally been cut before, effectively interrupting access for the mountain towns.

“It’s a major concern I have,” he says. “We do have to be adaptable and figure out what’s going to work best for that particular patient or area of the community.”

To increase access for the even smaller communities of Butte Falls and Prospect in Southern Oregon, North says Rogue Community Health partnered with each area’s charter school. The organization provides school-based health services, including telemedicine, and in return gets internet access in those communities.

“I think the biggest challenge [is] technology,” he says. “Do they have a phone? Do they have internet connection? Do they have a computer that they can work from?”

In addition to the hardware constraints of telemedicine, access also means being able to understand the telemedicine platforms. Costantini says this was important in developing the Bright.md health app, which first launched in 2014.

The app uses a fourth-grade reading level language, removing often confusing medical jargon, and is gender inclusive and available in Spanish. “Folks who don’t have English as their native language often struggle with health-access disparities,” he says.

The pandemic has proven that working remotely, including in health care, can be done. Telemedicine is not a replacement for seeing a doctor in person; but for many across the state, it has become a convenient, safe alternative.

Medical professionals are optimistic about the future of their industry and hope it includes a fair, long-term payment structure.

In the meantime, Elizabeth Powers still spends hours on the road visiting patients too far away to come to her office at Winding Waters, and video-chatting with many others from behind her desk. “It has definitely lowered barriers,” she says. “You just can’t go back from knowing that you can.”

To subscribe to Oregon Business, click here.